By Alex Gerrish

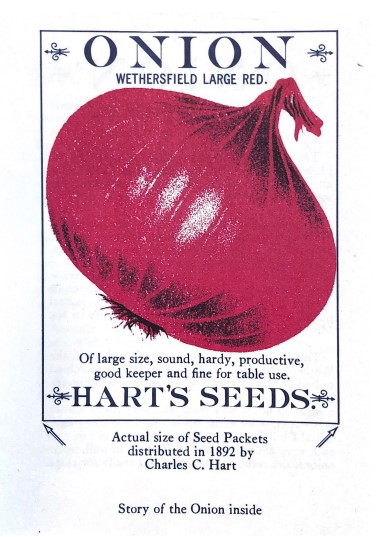

Known as Oniontown, Wethersfield, Connecticut is famous for its red onions. For years, the onion trade supported Wethersfield as the first commercial town along the Connecticut River, until the 19th century, when the town transitioned to the seed trade. Even today, Wethersfield celebrates its onion past with themed events, mascots, and other imagery across town.

A Budding Community

Field of Onions at Wethersfield – Courtesy of the Wethersfield Historical Society

One of the oldest English settlements in Connecticut, Wethersfield differed from other settlements in that it was primarily founded as a commercial society (rather than a religious one). Located in the Connecticut River Valley, its rich soil was perfect for the growth of red onions. Farmers grew Wethersfield red onions predominantly in the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries. These iconic vegetables took the world by storm and their trade reached its height in the 18th century. At that time, Wethersfield exported up to 1.5 million five-pound onion ropes (sheins).

Slavery played a role in the commercial success of the red onions. In fact, Wethersfield was an integral part of the slave trade in Connecticut through the Triangular Trade Route. According to the Wethersfield Historical Society, “flour, corn, peas, oats, and wheat, as well as the famous Wethersfield red onion, bricks, livestock, pigs, barreled salted meat and fish, and horses” were all sent to the West Indies in exchange for sugar, molasses, rum, and enslaved people. As a cheap source of vitamin C, many of the onions sent to the Caribbean fed enslaved people, providing food in an area that was otherwise filled with sugar crops.

In Connecticut, locals sometimes used the onions as payment. The Wethersfield Congregational Church—now known as “the church that onions built”—paid town taxes in onions for many years and to this day, the Wethersfield Historical Society pays its rent to the town in red onions.

The Onion Maidens

Famously, women played a significant role in onion farming. These hard-working women, known as the “Onion Maidens,” have been the subject of fable and controversy for years as a result of one infamous Connecticut resident and British sympathizer, Samuel Peters.

Born in 1735, Peters was a Tory—an American who supported British rule. As a resident of Hebron, Peters frequently voiced his allegiance to England. After receiving pushback in his community and being forced to publicly renounce his beliefs, Peters moved to England. There, he continued bashing Connecticut and published his infamous 1780 book, General History of Connecticut, which is littered with criticisms and outright lies regarding Connecticut history—including the myth of the Onion Maidens.

Peters’ General History of Connecticut established the myth that Wethersfield women were inspired to work on onion farms in order to receive silk dresses. In his description of the town, Peters writes, “it is a rule with parents to buy annually a silk gown for each daughter above seven years old, till she is married. The young beauty is obliged, in return, to weed a patch of onions with her own hands.” Furthermore, he states that the onion maidens were “ridiculed by the ladies of other towns…while the gentlemen…forget not the Weathersfield [sic] ladies’ silken industry.” This myth is largely untrue as silk was quite sparse at that time. Additionally, it suggests that the maidens farmed onions in order to attract the attention of prominent gentlemen, which is now regarded simply as legend. Still, this tall tale became ingrained in Wethersfield lore over the years thanks to numerous subsequent publications.

A later perpetuation of the myth came in the form of a 20th-century children’s book, Onion Maidens by A. K. Roche, which adapts Peters’ history for a younger audience. It tells the story of how women of affluent Connecticut cities—such as Newington and Glastonbury—incessantly teased the onion-farming Wethersfield women. These women soon discovered that the men from Hartford were “led astray” to Wethersfield where they smelled the red onions and were swooned by the hardworking Wethersfield women. Despite the many myths about their compensation, the Wethersfield women who farmed red onions were very real and supported the spread of the crop throughout Wethersfield and the world.

Planting New Seeds

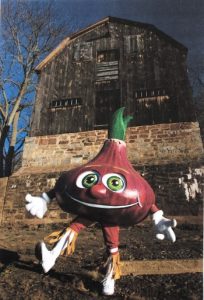

Wethersfield Onion Mascot – Courtesy of the Wethersfield Historical Society

The onion trade declined in the 19th century. While some believe it was a result of a root disease, others cite the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which banned slavery in England and its territories. Since this act affected the British territories in the Caribbean, the large amount of onions sent to enslaved people quickly diminished.

Despite the decline of its main export, Wethersfield quickly transitioned to the seed business to great success. Companies such as Comstock, Ferre, & Co. and the Charles Hart Seed Industry exploded in popularity, creating large fortunes. The legacies of these companies are still visible in Wethersfield today. For example, fortunes from Johnson, Robbins, & Co., another prominent seed company, funded the historic Silas W. Robbins House which is still standing.

Onions continue to remain an integral part of Wethersfield culture. Although visitors’ noses are no longer assaulted by the smell of red onions upon visiting, onion-themed imagery can be found everywhere, from the town welcome sign to annual events. For use at special occasions, a local artist, Phil Lohman, created a large, googly-eyed red onion mascot costume that has appeared in parades and celebrations since the 1980s. In 2018, Wethersfield Tourism sponsored a “Wethersfield Red Onion Recipe Contest” and Wethersfield’s annual “Bicycles On Main” celebration includes a decorated onion-themed bicycle set up in front of the Old Academy Building. Much like the iconic red onion, Wethersfield has an undeniably layered history.

Alex Gerrish is the Programs Manager at the Noah Webster House and holds a B.A. in American Studies from Western New England University. He would like to extend a special thanks to the Wethersfield Historical Society for their assistance with the research for this article.