By Edward T. Howe

The Monumental Bronze Company of Bridgeport was the only producer of a unique type of grave marker in the United States between 1874 and 1914. Other firms produced white bronze decorations (e.g., urns and civic monuments), but not grave markers.

Although the material used in the markers was dubbed “white bronze,” it was neither white (but bluish-gray) nor bronze (but pure zinc). The memorials varied in size from a few inches (i.e., a small “stone” with a name empaneled) to larger monuments or statues that reached over 25 feet high.

The Monumental Bronze Company Takes Shape

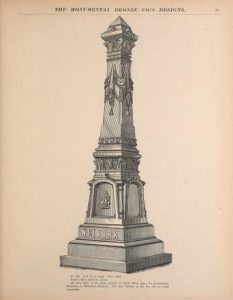

Design offered in the catalogue of the Monumental Bronze Company, October 1882.

The company that produced them began in 1873 in Chautauqua County, New York, when M. A. Richardson and his partner, C. J. Willard, developed a cemetery marker using zinc. The manufacturing rights to this product were eventually sold to the Wilson, Parsons and Company of Bridgeport in 1874. The company subsequently became known as Schuyler, Parsons, Landon and Company from 1877 to 1879. In 1879 it incorporated as the Monumental Bronze Company. According to an 1882 catalog, it offered “monuments, statues, portrait medallions, busts, and ornamental artwork for cemeteries, public and private grounds, and buildings.”

During its history, the company produced grave markers cast in zinc made from sand molds that were fused together, sandblasted, and lacquered to produce the bluish-gray finished product that imitated stone. The original casting was done in the Bridgeport foundry. Subsidiaries in Chicago, Detroit, Des Moines, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and St. Thomas, Canada became finishing and distribution centers. Since Bridgeport and its subsidiaries did not have showrooms, grave markers were sold through catalogs and part-time salesmen.

Although the company did supply numerous Union and Confederate Civil War monuments to other states, it made only one Connecticut monument. Its Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Academy Hill Park in Stratford was dedicated on October 3, 1889, to celebrate the town’s 250th anniversary. The elaborately-styled monument, with an overall height of about 35 feet, is topped with a standard-bearer figure on a pedestal.

Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, Academy Hill Park, Stratford, CT. – Connecticut Historical Society, Connecticut’s Civil War Monuments

The company also made a John Benson Marker, dedicated around 1884, that stands in Stratford. Located in Putney-Oronoque Cemetery, it has a height of 22 inches. It identifies–significantly–the deceased as “colored” on the front side; a rare recognition of the service provided by African American Civil War soldiers. The reverse side shows a raised figure of a soldier with a musket butt near his right foot.

World War I Brings Change

The company’s products continued their popularity throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as consumers often deemed the marble and granite products sold by their competitors to be too expensive. But in 1914, the federal government took over the company facilities in order to make gun mounts and munitions for World War I and the firm never produced another grave marker.

After the war, Monumental Bronze executives realized that public demand had significantly shifted away from white bronze toward granite and other natural stones. Demand further declined when many cemeteries began prohibiting metal grave markers. Nevertheless, business continued with the production of metal panels used for adding the names of more family members to existing monuments, as well as fabricated castings for automobile and radio parts and kitchen equipment. Its increasingly unprofitable business during the Great Depression, however, resulted in the company declaring bankruptcy in 1939.

Edward T. Howe, Ph.D., is a Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at Siena College near Albany, New York.