By Susan Campbell for the Shoreline Times

She co-wrote Connecticut’s first property law for women. She campaigned against slavery at a time when genteel Hartford society did not do such things. She wrote thoughtful, creative magazine pieces, testified before the US Congress and Hartford’s legislators, and politicked and cajoled for votes for women. Yet Isabella Beecher Hooker does not inhabit many historical records. She is mentioned only briefly, and often accompanied by the dismissive qualifier, “eccentric.”

Isabella Beecher Hooker was the younger half-sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Her family raised her to be a “Fabulous Beecher”—to believe that she had a destiny to fulfill. She reluctantly married a man who became her fiercest editor and strongest supporter. She had children with whom she was never quite comfortable, and kept a series of revealing journals the family kept from the public for fear that they might reinforce the belief that she suffered from mental illness. Her own family members actually started the rumors of mentally impairment when she refused to side with them in defending her famous and respected half-brother, the minister Henry Ward Beecher, when he stood accused of adultery.

Isabella Beecher’s Formative Years

Isabella Beecher was born February 22, 1822, in Litchfield, then home to a progressive girls’ school, a well-known law school, and a popular church led by her father, the Rev. Lyman Beecher. The reverend first came to national prominence in the early 1800s preaching on Long Island, then moved on to Litchfield, Boston, and Ohio. Along the way, he married three wives, and buried two of them. Isabella was the product of his second marriage, to Harriet Porter Beecher, a woman of wealth who was in no way prepared to be the wife of a minister of much influence and small means, as well as the mother of eight children mourning the death of their mother, Lyman’s first wife, Roxanna.

Upon her marriage, Harriet Porter mostly retired to her bedroom. She died when Isabella was a teenager. Isabella lived with various older siblings before moving to Hartford to live more or less permanently with her sister Mary Beecher Perkins, and her husband, Hartford attorney Thomas Perkins. There, John Hooker, a scion of Connecticut history, noticed her. He was an enthusiastic suitor, but Isabella did not have any interest in marrying. She knew that the marriage contract was the last legal document a woman ever signed, and Isabella wanted none of that.

John proved persistent, however, and the couple wed after a two-year courtship conducted mostly by letters. Beecher was a brilliant and dedicated activist who committed to the abolitionist movement whole-heartedly and then, as had so many suffragists of her time, moved her attention to the enfranchisement of women.

Early in her adult life, she tamped down her intellect to focus on what the world told her was most important—her children. Her frustration began to build, however, when she realized that the focus of her attention would eventually grow up and leave her with a large Hartford house and too much time on her hands. She reached out to Elizabeth Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucretia Mott and other suffragists, and earned their trust, as well as their occasional dismay, as she did not always fall in-line with them, either.

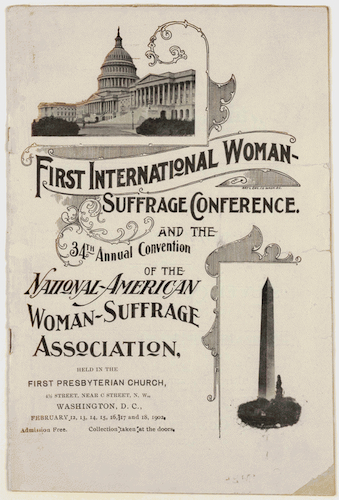

Convention program of the First International Woman Suffrage Conference and the 34th Annual Convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Washington, DC, 1902, where Isabella Beecher Hooker is listed as the President of the Connecticut chapter – Library of Congress, American Memory

Beecher went on to found the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, and help keep the national suffrage movement afloat for years by making significant contributions to it. In 1870, she and John wrote the law for their state legislator to introduce that granted property rights to women and they petitioned the Connecticut legislature for seven years until it finally passed.

The Beecher Scandal

When her brother, Henry Ward Beecher, stood accused of adultery by one of his parishioners, the Beecher family circled the wagons. Not Isabella, however. She knew his accuser and the newspaper publisher who broke the story. She believed—and history proved her right—that her brother was guilty. She asked him to repent, and then helpfully offered to preach at his Brooklyn, New York, church while he got right with God. He refused her offer, and though he stayed in touch through lovely letters, the rift never healed for some of her other family members, who promptly started rumors that Isabella did not possess a fit mind.

Her sister Harriet even wrote a satirical novel about the suffrage movement in which a thinly disguised Isabella appears as a naïve scatterbrain. People who wanted Henry Ward’s sex scandal to just go away were angry that Isabella was so outspoken about it. She never completely escaped the accusations of mental impairment, though she kept pushing.

Full-length portrait of Isabella Beecher Hooker – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Sewall Collection

Isabella was also a spiritualist. She believed that the veil separating the living and the dead was quite thin, and that the living and dead had the ability to correspond. She took great comfort in that belief, as did so many mourners reeling from losses inflicted during the Civil War. Some of the bold-faced names of the day dabbled in spirituality, including neighbor Mark Twain, who made public fun of spiritualism even though a spiritualist healed his wife when she was younger. But Isabella never dabbled. She was all in.

John preceded Isabella in death in 1901, and toward the end of her life she spent more and more time in her bedroom, awaiting word from John’s spirit. There were occasional forays into public, and she continued to lend her name to the Connecticut suffrage cause (in which she insisted the new generation be given a leadership role) but she suffered a stroke in January 1907, lingered a few days and then died—her legacy of establishing voting rights for women unfinished.

Susan Campbell is author of Tempest-Tossed: The Spirit of Isabella Beecher Hooker (Wesleyan University Press: 2014) and is the Robert C. Vance Chair for Journalism and Mass Communication at Central Connecticut State University. She is also a trustee at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House and Museum and a writing instructor at the Mark Twain House and Museum.