By Bryna O’Sullivan

In addition to the better-known Army and Navy, American colonists employed privateers as part of the military effort against the British during the American Revolution. Sometimes described as “legalized piracy,” privateers were privately-owned vessels who had the legal right to attack and capture British ships. In accordance with American law, privateers could redistribute the British ships and their contents as “prizes.” As they were privately owned, these ships impacted British shipping without becoming a drain on American resources. During the American Revolution, thousands of privateers supplemented the actions of the Continental Navy’s 57 vessels and cost the British millions of dollars.

How were privateers commissioned?

Privateering news in the Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer, July 13, 1779 – Connecticut State Library. Used through Public Domain.

There were two types of commissions issued to privateers during the American Revolution. The first was called a Letter of Marque. Commercial vessels requested a Letter of Marque from the government before each voyage and it allowed the vessel to attack a presumed enemy vessel. The second type, a Privateer Commission, allowed a vessel to focus entirely on disrupting shipping.

Privateers could receive their commission from either the Continental Congress or the state of Connecticut. On March 23, 1776, the Continental Congress passed an act establishing guidelines for privateer commissions. These commissions were crucial documents for privateer captains as they identified the vessel as working for a government rather than engaging in piracy. To receive either type of commission, a ship’s owners were required to post a bond to ensure the crew’s good behavior. During the American Revolution, colonial governments granted approximately 1,700 Letters of Marque and commissioned eight hundred privateers.

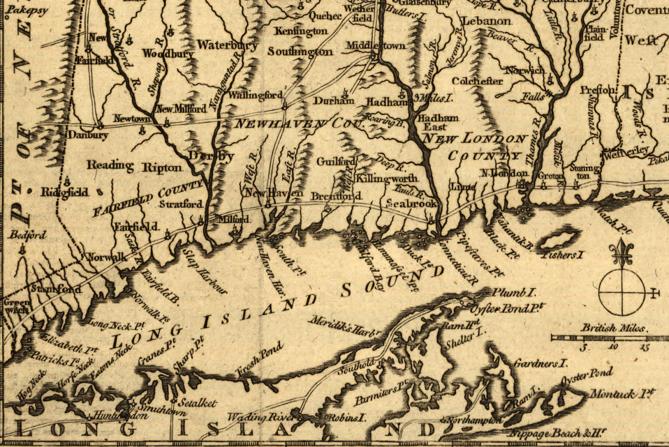

Connecticut issued most of its commissions to the whale boat fleet. This fleet was known for their attacks on British shipping in Long Island Sound as well as their periodic attacks on Long Island residents. Connecticut issued an estimated two hundred to three hundred commissions. Nathaniel Shaw, Jr., Connecticut’s Navy Agent, kept a record all of privateers operating in the state.

How did privateering work?

A privateer commission allowed a ship to attack and capture an enemy vessel, referred to as a prize. Once captured and brought to port, an inventory of the vessel and an account of the vessel’s capture was made. A prize court would then verify the legitimacy of the capture, help arrange for the sale of the ship and the contents, and divide profits from the prize among anyone who had legal claim. In Connecticut, the Maritime Courts served as prize courts—the Connecticut State Library holds the original records.

The division of the prize was a topic of debate throughout the Revolutionary period. Both the Continental Navy and the Connecticut State Navy allowed crews to keep a share of captured vessels. The original division was set by the Continental Congress—for merchant vessels, two-thirds of the value went to Congress or the state, and one-third to the crew. That was shifted by Congress in 1776 to a fifty/fifty split. Connecticut made no change. Privateer crews were consistently able to keep a larger portion of the prizes, which made it easier for crews to find sailors.

Where were privateers based in Connecticut?

Shaw Mansion in New London, March, 1940. – By Stanley P. Mixon, Wikimedia Commons. Used through Public Domain.

At least four Connecticut towns had registered privateers: Wethersfield, Norwich, New Haven, and New London. Wethersfield hosted at least 17 privateers between 1777 and 1780. Most were merchant ships, trying to make up for loss of trade due to the British blockade.

The privateers from Norwich are not well documented but may have been linked to its well-established shipbuilding trade. New Haven’s merchants purchased and outfitted their own ships, likely again seeking to make up trade. For example, merchant Adam Babcock sought leave from General George Washington to have his privateer travel with a Continental vessel in a letter from May 6, 1776:

“I heard a few Days since that your Excellency had fitted out an Armed Vessel under the Command of Capt. Perrit to Cruise to the Southward—should that be the Case—I beg leave to propose that a Vessel I have fitted out commanded by Capn Brooks may go out in Company with her, which will make them both quite secure against any Thing they may chance to meet with in getting off the Coast, except they should fall in with a Man of War.”

New London was especially known for the impact of its privateers. Its location near New York, in the shelter of a river, with easy access to multiple bodies of water, made it an ideal port. Retaliation and a desire to limit privateering activities partially motivated the British Army’s attack on New London on September 6, 1781. While the Battle of Groton Heights did result in the loss of around ten ships, most escaped upriver.

As naval agent for both the Continental Congress and the State of Connecticut, Nathaniel Shaw, Jr. ran his operational command post out of the Shaw Mansion in New London. Shaw also personally invested in privateering vessels. Today, the Shaw Mansion serves as the headquarters for the New London County Historical Society.

Privateering’s Impact on Connecticut

The legacy of Connecticut’s privateers is complicated. The practice had a documented impact on British shipping. Privateering provided a way for ships’ owners to replace income when British blockades began to limit their access to traditional trade routes. This permitted the ship’s diverse crew, who may have had challenges seeking employment elsewhere, to maintain their roles.

At the same time, privateering was a risky financial venture—not every voyage resulted in the successful capture of a prize. Ships were lost and unlawfully captured—shipowners had to pay required costs to have them restored. Privateers themselves could be captured and imprisoned. Privateers were also faced with a perpetual question of whether they were acting out of patriotism or self-interest. Yet, even with a complicated legacy, privateers were a major part of American success in the American Revolution.

Bryna O’Sullivan is a professional genealogist and French to English genealogical translator.