By David Drury

John Ledyard, one of the most adventurous figures in Connecticut’s long history, would have made a great fictional character had he not been real.

Born a ship captain’s son in Groton in 1751, Ledyard, when just a young man, canoed solo down the Connecticut River from Dartmouth College to Hartford. He sailed uncharted waters with Captain James Cook and wrote a best-selling journal about the navigator’s fatal third voyage. He trekked across Siberia and was arrested as a spy. And, living on the edge until the very end, he died in an Egyptian hovel in January 1789 while preparing to explore the African continent.

Ledyard’s passing saddened his many friends and admirers who included such luminaries as Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, the Marquis de Lafayette, and John Paul Jones. Jefferson himself helped cement his friend’s posthumous legacy as Ledyard the Traveler. “…a man of genius, of some science, and of fearless courage and enterprise,” Jefferson recalled in his 1821 autobiography. The two had met in Paris in 1786 and Jefferson had hoped Ledyard would become the first white man to traverse the North American continent, an accomplishment that might have eclipsed Jefferson’s later Corps of Discovery, better known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The Young Ledyard

As a boy, John Ledyard grew up in thriving New London County, where the West Indian trade made fortunes for enterprising merchants and captains. But there were always risks, and when John was 11, his father, known as Captain John, and an uncle, Youngs Ledyard, died of disease while at sea. Young John and two cousins were sent to live in Hartford with their parental grandfather, the formidable Squire John Ledyard, who provided his grandson with room, board, and a solid education.

After Squire John’s death in 1771, John became the ward of his uncle, Thomas Seymour, and apprenticed in Seymour’s law office, but a different path opened for him in the spring of 1772 when he enrolled at Dartmouth. The college, the creation of former Connecticut preacher Reverend Eleazar Wheelock, had opened in the rustic New Hampshire woodlands just two years before.

From the moment he arrived, fashionably dressed and riding in a horse-drawn sulky, until his escape downriver in a 40-foot dugout canoe a year later, Ledyard alternately antagonized Wheelock and fascinated his fellow students. His ability to adapt to cultures and peoples different from his own became evident when he spent several months traveling and living in the woods, conversing and learning from the area’s indigenous people. His canoe escape became part of Dartmouth lore and is commemorated each year by a springtime float trip by members of the Ledyard Canoe Club who journey from Hanover, New Hampshire, to Old Saybrook, Connecticut.

After leaving Dartmouth, Ledyard sought to launch a career in the ministry, making contacts in eastern Connecticut and Long Island, where his mother had settled after her remarriage. Failing that, he spent a year as a merchant seaman, returning to Connecticut in the summer of 1774.

Stint as a British Soldier

In March 1775, just as revolution was about to erupt in the colonies, Ledyard boarded a ship to England where he enlisted in the British Army. Four months later, in July, he transferred into the British Navy, joining the Royal Marines, and exactly one year later, in July 1776, he left Plymouth harbor aboard Captain Cook’s HMS Resolution to begin the voyage of a lifetime.

His four years, two months, and 24 days spent at sea was the pivotal event in Ledyard’s life. From Britain, the Resolution and its sister ship Discovery sailed south and east, around the Cape of Good Hope, across the southern Indian Ocean to Tasmania, New Zealand, and from there to the various Polynesian island chains of the South Pacific, where Ledyard was believed to be the first Euro-American to be tattooed.

Francesco Bartolozzi, The Death of Captain Cook, 1784, engraving

The expedition continued north and eastward reaching the Pacific Northwest coast of North America. It then sailed north, probing the Alaskan coastline in search of a Northwest Passage. The onset of winter weather forced a return to the Sandwich Islands (the Hawaiian chain) where Cook met his end in February 1779. Then it was north, northwest to Siberia, south along the coast of China and Indonesia, and back to the Indian Ocean and homeward bound. The voyagers returned to England in October 1780.

A World Adventurer is Born

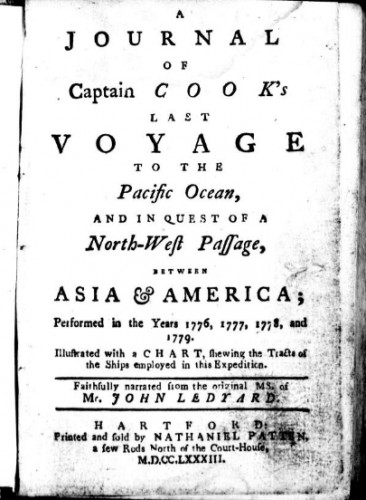

In January 1783, after deserting the British Navy, Ledyard returned to Hartford. Using Seymour’s law office, he penned largely from memory his account of Cook’s voyage. The work became a best seller and a footnote in the nation’s legal history, after Ledyard’s petition to the General Assembly seeking copyright protection provoked a series of state laws that codified that right. Eventually, a federal copyright law was adopted in 1790.

Though portions of Ledyard’s A Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage were later shown to have been plagiarized–perhaps by the publisher–and his supposed eyewitness account of Cook’s death remains controversial, the journal remains a compelling document. Ledyard was a keen observer of the peoples and cultures he encountered, and his journal contains detailed descriptions of clothing, adornments, foods, and rituals.

A Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage to the Pacific Ocean by John Ledyard

Ledyard was quick to grasp the similarities of language and customs between far-flung groups of people. For instance, after meeting a group of Natives in what is now British Columbia, and calling upon his familiarity with native peoples from his Dartmouth days, he concluded, “I had no longer beheld these Americans than I set them down for the same kind of people that inhabit the opposite side of the continent.” A few years later, he would record that, based on his own observations from deep within the Russian Empire, it appeared that Native Americans originally had migrated from Asia, a conclusion supported by many anthropologists and archaeologists today.

Ledyard was convinced that a fortune could be made in trading North American furs with China. He spent two years pitching the idea to potential investors in the US and Europe, before arriving in Paris in mid-1785. There he met Jefferson, Lafayette, and Benjamin Franklin and was drawn into the fabulous and seedy carnival that was life in the French capital in the last years of the ancien Régime.

Ledyard’s tales from his travels ignited Jefferson’s interest in unlocking the secrets held in the vast expanse of North America between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Pacific Ocean. From those conversations emerged a staggeringly audacious plan: Ledyard would travel across Europe and Asia, cross over to the North American continent, and continue on foot to the East Coast of America.

With little money and possessing scarcely more than the clothes on his back, Ledyard left the port of Hamburg in December 1786. From there, he visited Copenhagen and Stockholm, then made a punishing 1,400-mile, mid-winter traverse of the Gulf of Bothnia, reaching St. Petersburg in March 1787.

In June 1787, accompanied by a traveling companion, Ledyard set off in a kibitka, a coach drawn by three horses, across Russia, the Urals, and Siberia. He ultimately reached the village of Yakutsk, a journey of about 4,000 miles. Extreme heat, bitter cold, dust, and flooded roads didn’t stop him, but the Russian authorities did. They were suspicious that his real purpose was to unlock the secrets of their fur trade monopoly. His letters to friends and patrons again show Ledyard as a keen, sympathetic observer of the myriad of native peoples who inhabited the far reaches of the Russian Empire.

He was, as in his earlier travels, attentive to the women he met, observing in the journal that he kept, “the Woman whereever found is the same kind, civil, obliging, humane, tender being; that she is ever inclined to be gay & cheerful; timorous & modest; that she does not hesitate like Man to do a generous action of any kind.”

Chased out of Russia, Ledyard found his way back in London, where in June of 1788 a group of gentlemen formed the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa. Ledyard seemed the perfect choice for exploring the mysterious continent. He was hired, and after a brief stopover in France to visit old friends, including Jefferson, Ledyard set off for Cairo where he died unexpectedly, possibly from an overdose of an acid then used to treat enteric (intestinal) illnesses, before he could embark on what would have been his next great adventure.

David Drury, a retired editor of The Hartford Courant and lifelong student of history, regularly contributes articles about Connecticut history to The Courant and other publications.