By Mariel Hohmann

In the middle of the 19th century, a movement swept through the nation that formed a profound bond between the natural world and human death. This movement was one toward the creation of rural cemeteries, which allowed for burial grounds to be landscaped into serene environments full of grass, trees, gardens, and winding paths. It was a direct response to growing industrialization, which took people away from nature. Although these park-like cemeteries imitated nature, they were still the result of meticulous planning and landscape modification, which was anything but natural. Indian Hill Cemetery in Middletown, Connecticut, displays many characteristics of this Rural Cemetery Movement and provides meaningful insight about the way Americans perceived their environment.

The Rural Cemetery Movement Comes to Middletown

In September of 1850, Middletown founded its own landscaped burial ground: Indian Hill Cemetery. At Indian Hill’s opening, one of the cemetery’s directors, Austin Baldwin, placed this new burial ground in the scope of the larger Rural Cemetery Movement. He described how the rural cemeteries sweeping the nation were a response to the way in which highly populated and industrialized cities laid old cemeteries to waste. Previously, cemeteries had been tiny, unorganized spaces often built upon or entirely vacated to allow for city growth. Places like Indian Hill allowed for seclusion and peace where the living honored the dead without the fear of encroaching society desecrating their graves.

The Chapel at Indian Hill Cemetery – Indian Hill Cemetery Association

Indian Hill found respite from the bustling streets of Middletown. The hill on which the cemetery lies was about a mile from Main Street, the commercial center of the town. The area in-between contained only a small human population and instead filled itself with plants and woods. From Indian Hill, visitors saw the surrounding hills, farmland, and woodland as they walked among the graves. To the cemetery’s proprietors, the land seemed almost sacred in its natural beauty and serenity.

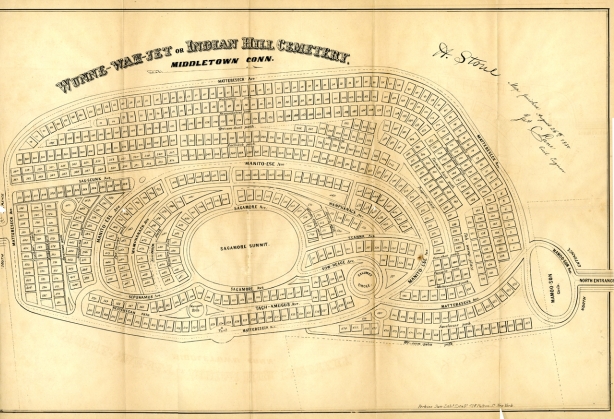

In its design, Indian Hill continued the tradition of garden-like cemeteries. Its shape was a winding oval. Paths curved and flowed throughout the space. There were fields where one found open space and plant life peppered throughout. It was truly a sanctuary.

An American View of Nature Depicted through Cemeteries

Industrialization in the 19th century drove more and more people into cities, forcing them to find nature in cemeteries. As the century progressed, agriculture in New England suffered from soil exhaustion and the effects of increasing populations. Some relief came in the form of waterpower. This new found ability to transform water into energy allowed factory towns to thrive along rivers. Around the turn of the century, populations flowed from rural landscapes into these industrialized river towns, like Middletown.

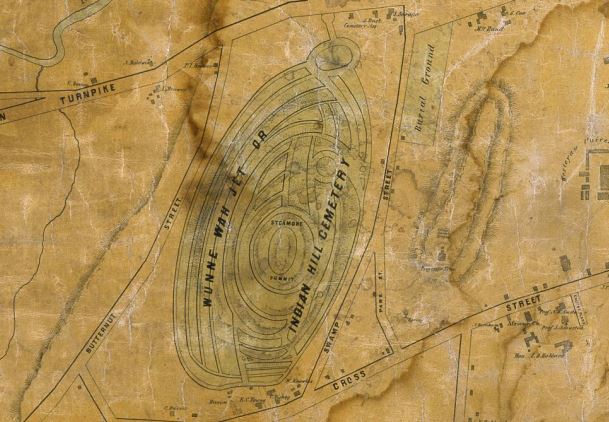

Detail from a Map of the City of Middletown, Connecticut, Surveyed by R. Whiteford: Published by Richard Clark, 1851 – Connecticut Historical Society

Meanwhile, industrialization deprived factory towns of rural qualities. The built environment readily consumed them. Natural parks, often considered ubiquitous in today’s towns, proved difficult to find. Even cemeteries, with their cramped rows, looked like city streets.

Americans soon turned to romanticism and escaped to the countryside. During the 19th century, romantic depictions of nature in the form of landscape painting thrived. Citizens of industrialized areas attempted to escape their urban lives through the appreciation of landscape art and painters. Consequently, artists in the Hudson River School, such as Thomas Cole, became some of the most successful artists in the nation. Simultaneously, tourism from cities into rural areas became extremely popular.

Entrance gate to Indian Hill Cemetery – Indian Hill Cemetery Association

Art and tourism were not enough for urbanites, however, and they eventually demanded public, natural spaces in town. In 1831, with the creation of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, the United States began its journey toward the integration of rural landscapes with cemeteries. Citizens across the country coveted the connection to nature that Mount Auburn provided, resulting in the cemetery quickly becoming one of the biggest tourist attractions in the nation. By supporting rural cemeteries, Americans expressed their need to connect with nature.

The clergymen and upper-class founders of Indian Hill not only saw their cemetery as an escape to nature, but as an opportunity to commune with it during times of mourning. To Indian Hill’s founders, the plants and scenery of their cemetery soothed mourners at their most vulnerable times. As Reverend Frederic J. Goodwin said at the opening of the cemetery, the grave was to be associated with “the idea of cheerfulness and hope; of warm suns and green verdure, and blooming flowers.” To him, a space had been created with no trace of gloom. He wanted nature to become a space of meditation and spirituality, where a peaceful afterlife could be both contemplated and reached.

Although the 19th century was a time of great industrialization, Americans also saw the aesthetic and moral value of their environment. They exploited the land for its agricultural potential and energy, but simultaneously saw it as a source of stunning landscapes and as a place for recuperation.

Indian Hill Cemetery: An Unnatural Nature

Rural cemeteries allowed Americans to connect with the land while still being close to home, but the nature they communed with was one of human design. Indian Hill was not a wild ecosystem. It was a meticulously designed landscape. Every plant was groomed, every path planned out, every field trimmed, and every lot well kept. The cemetery’s by-laws purported to ensure each tree, shrub, and flower received protection from destruction by visitors. If one of these plants got in the way of a path or a lot, however, the cemetery removed it immediately. Above all, the goal of the cemetery was to make the land into something practical and aesthetically pleasing, not wild.

Map of Indian Hill Cemetery, 1850 Special Collections and Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University

With the creation of Indian Hill Cemetery, Middletown found its place in the American rural cemetery tradition. The cemetery allowed Middletown residents, ever-frustrated by an increasingly industrialized society, to escape to nature and entwine it with death and the afterlife. The nature they sought to experience was never truly wild, however. As close as 19th-century Americans became with nature, it always remained a nature affected by human design.

Mariel Hohmann wrote this piece while a student studying chemistry and environmental history at Wesleyan University during the 2014-2015 academic year.