By Emily E. Gifford

In the early 19th century Hartford dentists Horace Wells and William Morton played instrumental roles in the development of anesthesia for dental and other medical applications. Horace Wells, born in Hartford, Vermont, and educated in Boston, began his practice in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1836 and quickly rose to prominence. He married Elizabeth Wales in 1838 and continued to write about dentistry and invent various devices, such as a foot-powered shower.

Wells Sees Potential in Laughing Gas

In 1842, Wells took Morton, first, as his student and then as his partner. Morton, who was born in Massachusetts and trained for dentistry in Baltimore, Maryland, married Elizabeth Whitman, daughter of Lemuel Whitman, on her father’s condition that he quit dentistry and study to practice medicine instead. In 1844, Morton began (but never completed) his studies at Harvard Medical College.

Although Wells tried to form a dentistry practice with Morton in Massachusetts, the new partnership lasted less than two weeks, and Wells returned to Connecticut. In December of 1844, Wells and his wife attended a demonstration at Union Hall in Hartford of “laughing gas” (nitrous oxide) put on by showman Gardner Colton, who had briefly studied medicine. Wells noticed that one of the volunteers, while ingesting the gas to the amusement of the audience, had injured his leg during the demonstration. Wells later talked to the man and found he was unaware he had suffered an injury.

Since Wells had long been concerned about the amount of pain suffered by his patients during dental procedures, he immediately enlisted Colton’s help. The day after the demonstration, Colton came to Wells’s practice and administered nitrous oxide while Wells’s associate, John Riggs, extracted one of Wells’s own troublesome wisdom teeth. Feeling not “so much as the prick of a pin” in the course of this usually painful procedure, Wells believed that he, with the help of Colton and Riggs, had invented painless dentistry.

Cover of Dr. Horace Wells’ Day Book – Connecticut Historical Society

Experiments with Anesthesia

After Colton taught Wells how to administer the gas, Wells performed a dozen painless procedures over the next few weeks. Always intense, Wells became more excited with each successful procedure. He decided to demonstrate painless dentistry in Boston and did so in January of 1845 at Massachusetts General Hospital for the benefit of Harvard Medical School students and faculty members. The demonstration did not go well. The patient moaned as if in pain, and the audience drove Wells from the lecture hall with cries of “Humbug” and “Swindler,” even though the patient tried to explain that he was not, in fact, in pain.

Despite his setback in Boston, Wells continued to use nitrous oxide in his practice in Hartford and freely shared his discovery area dentists. While dental patients elsewhere continued to suffer, many throughout Hartford were enjoying painless dentistry by the middle of 1845. Wells’s apparent failure in Boston, however, temporarily deterred him from any further attempts to publicize his innovation nationally.

Meanwhile, in Boston, Wells’s former partner Morton was experimenting with the use of ether as an anesthetic. In 1846, Morton demonstrated the use of ether to perform a painless tooth extraction. He did not, however, identify his anesthetic as being ether. Instead, Morton called it “letheon” and applied for a patent for his “substance.” He established a monopoly on painless dentistry in the Boston area and soon got positive publicity for his discovery of ether’s medical applications. Morton also tried to make a profit from his discovery, but his attempts to claim sole discovery of anesthesia in general and ether in particular were denied.

Both Horace Wells and Charles Jackson, who had been Morton’s chemistry professor at Harvard and originally introduced him to ether, stepped forward to challenge Morton’s claim that he had discovered anesthesia. Wells, for his part, sought to strengthen his claims by publishing History of the Discovery of the Application of Nitrous Oxide, Ether, and Other Vapors, to Surgical Operations (1847). Morton and Jackson entered into protracted legal battles in their attempts to prove their claims.

Wells Seeks Fortune in NYC

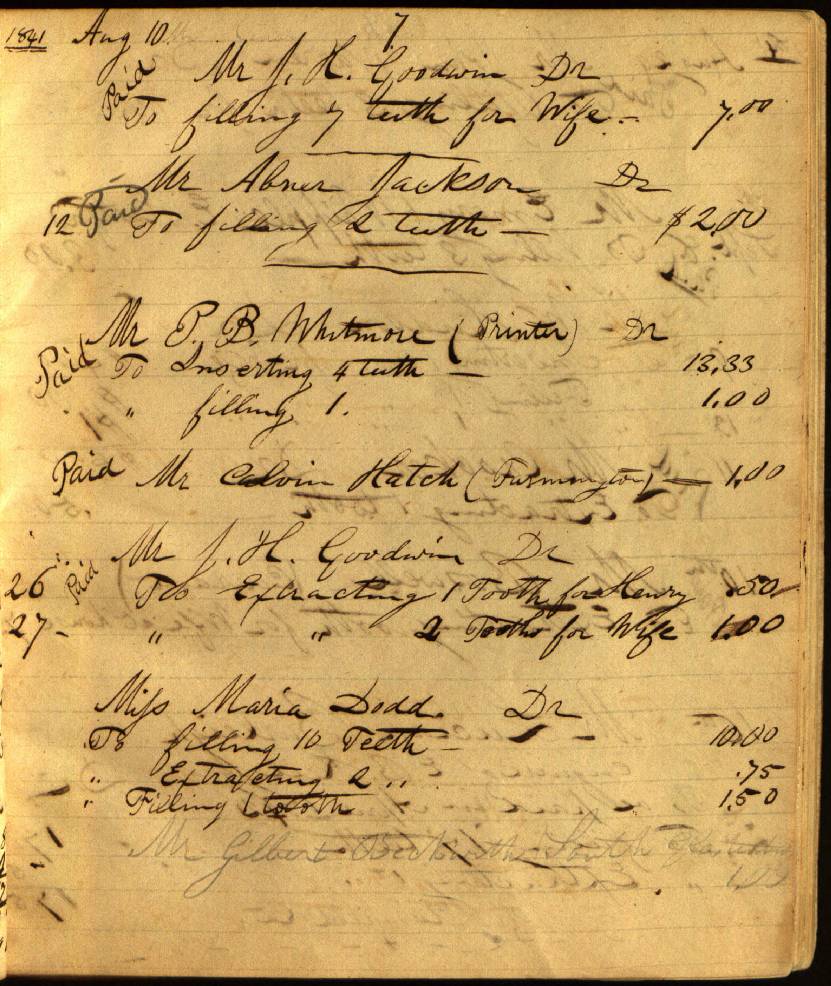

Page from Horace Wells day book detailing patient dental work – Connecticut Historical Society

Wells was also trying to find a way to gain fame and fortune as an anesthetist. By the end of 1847, he had participated in dental and other surgical procedures in Hartford, but decided that he should relocate to New York City to achieve greater recognition and success.

He moved there in January of 1848, intending to establish himself before sending for his wife and their young son, Charles Wells. Loneliness and homesickness overcame him, however, and Wells began using ether and chloroform in an attempt to ease his depression. Wells spent several days intoxicated on the combination of drugs, eventually becoming so confused that he could not distinguish sleep, dreams, and reality.

On the night of his 33rd birthday, Wells went out and threw acid on a pair of women in the street. Fortunately, the acid only burned their clothing and did not permanently injure the women. The police responded to their cries for help and arrested Wells, who they incarcerated in the Tombs Prison. He continued to ingest chloroform and ether while in jail, but in moments of clarity realized the depths to which he had sunk.

Believing that he had disgraced himself and his family beyond repair, Wells took a large dose of chloroform and used a razor to slash a major artery on his thigh. He quickly bled to death, and his body was released to his family for burial at Old North Burying Ground in Hartford. In 1908, Charles Wells re-buried his father and mother (who had died in 1889 and been buried alongside her husband) at Cedar Hill Cemetery. Wells’s tombstone identifies him as the “discoverer of anesthesia.” (In like fashion, Morton’s stone acclaims him as the “Inventor and Revealer of Inhalation Anesthesia.”)

The Nature of Discovery

In 1864, the American Dental Association, followed by the American Medical Association in 1870, recognized Horace Wells as the discoverer of anesthesia. Morton was never able to gain the fortune he sought for his own contributions to the field, including a $100,000 prize which was contested by Jackson and Wells’s survivors.

Although claims to singular discovery reinforce society’s fascination with individual genius, historians of science note that it is not unusual for innovations to occur at a moment when several individuals—sometimes with knowledge of each others’ efforts and sometimes not—are working along similar lines. Discovery, they emphasize, is not typically an event but a process. Wells, then, is rightly recognized for his pioneering role in pain-free dentistry and the field of medical anesthesia.

Emily E. Gifford is an independent historian specializing in the history of religion and social movements in the United States.