By Patrick J. Mahoney

In 1826, during the Second Great Awakening, Protestant faiths drew new converts across the United States and a renewed focus fell upon proper social and religious behaviors. It was amid these circumstances that Lyman Beecher stood before his congregation in Litchfield, Connecticut, to deliver a series of sermons on the nature and dangers of intemperance. Regarding the threat that excessive alcohol consumption posed to the future success of the young nation, the fiery preacher noted, “Intemperance is the sin of our land, and, with our boundless prosperity, is coming in upon us like a flood; and if anything shall defeat the hopes of the world, which hand upon our experiment of civil liberty, it is that river of fire which is rolling through the land, destroying the vital air and extending around an atmosphere of death.”

Shortly after their delivery and publication, Beecher’s sermons on intemperance found a growing audience throughout the United States, England, and the European continent. His outspoken stance on the issue was only one example of Beecher’s moral leadership and guidance during a time of great religious change in America.

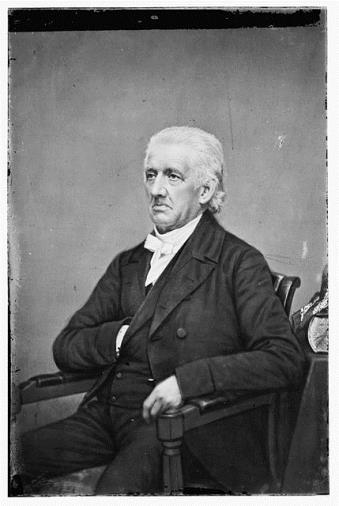

Reverend Lyman Beecher, ca. 1855-1865 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection

Entering Life as a Preacher

Born in 1775, Lyman Beecher was a native of New Haven, the son of David Beecher and Esther Hawley Lyman. At the age of 18, he entered Yale, where he studied under the renowned New England Congregationalist minister and President of Yale, Timothy Dwight. Following his graduation from the Yale Divinity School, Beecher entered his first preaching post as an understudy at the Presbyterian Church of East Hampton, Long Island. It was in 1810 that Beecher moved to Litchfield, Connecticut, to preach at the Congregational Church. He quickly became a fixture in the Litchfield community and remained there for nearly three decades.

As the 19th century progressed, however, tales from travelers to the western territories began to circulate around the eastern seaboard, bringing about a renewed sense of interest in the potential of the region. Among those captivated by “the West” was Beecher. Reflecting on its diverse population, and the lack of influence from established societal institutions, Beecher noted that the future vitality of the region depended on the education and moral culture introduced by proper religious elements. To this end, he warned against what he deemed to be the increasingly pervasive influence of the Roman Catholic Church. He argued that if the Catholic Church became a major influence in the West, its legacy of corruption might be the downfall of the region.

Lyman Beecher in Cincinnati

Unsurprisingly, given his avowed interest in the future of the region, Beecher moved his family west to Cincinnati in 1832, where he accepted a position as president of Lane Theological Seminary. Far from the quaint environs of East Hampton or Litchfield, Cincinnati was a bustling city, deemed by Beecher to be the “London of the West.” Marked by the goal of preparing a crop of protestant ministers suitable for evangelizing the sprawling American West, Beecher’s presidency became marked by controversy.

Shortly after Beecher’s arrival, the national debate on slavery divided the faculty and students at the school. In the end, many of the students who adopted an abolitionary stance felt discordance with the school’s faculty and board of directors, and withdrew to attend the newly founded Oberlin College.

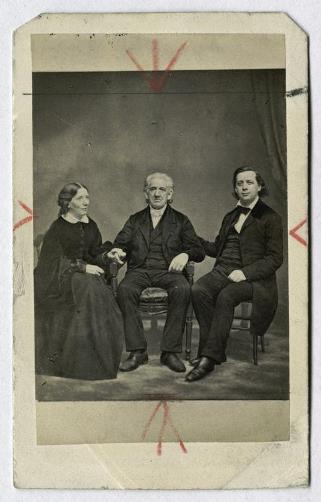

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lyman Beecher, and Henry Ward Beecher from a carte de visite by Mathew Brady – New York Public Library Digital Collections

Despite his concerns about the increased influence of the Catholic Church, it was traditional Calvinists within his own faith, namely the Reverend Joshua Lacy Wilson, who took issue with Beecher’s delivery and message of faith. His detractors, including Wilson, pointed to what they perceived as Beecher’s non-traditional methods for evangelization and charged him with heresy and slander in 1835. Although later acquitted of all charges, Beecher felt the reproach of the claims against him lingered for the duration of his time in Cincinnati. He remained another 16 years in his position at Lane Seminary and as pastor of the city’s Second Presbyterian Church before heading back east in 1851. He spent the remainder of his days in Brooklyn, New York, where he died on January 10, 1863, at the age of 87.

While Beecher was a leading religious revivalist, social reformer, and shaper of American religious identity in the 19th century, his legacy exceeds that of his ministry. Of the 13 children that he fathered during his three marriages, all seven of his sons (including Henry Ward Beecher) followed him into religious life. Additionally, his daughters Catharine and Isabella entered public life as advocates for educational reform and suffrage respectively. His daughter, Harriet, however, became perhaps the most famous of his offspring after her authorship of the renowned abolitionist tract, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Patrick J. Mahoney is a Research Fellow in History & Culture at Drew University and former Fulbright scholar at the National University of Ireland Galway