By Michael Sturges

In the early national period, following the Revolutionary War’s end in 1783, dependant adults, such as the elderly, disabled, or unemployed, would be cared for by their families within the home. In some towns and cities, the means existed for small almshouses to care for the unfortunate. Communities might also set up programs that contracted out the poor and disabled to labor at whatever tasks they could perform.

Such approaches made conspicuous the mentally ill, who could not easily fit into this early American system of family and community care. Options for these individuals typically focused on confinement.

Treatment of Mental Illness Evolves

At the outset of the 1800s, during a period of religious revitalization called the Second Great Awakening, concern for the care of dependants became infused with a missionary zeal. The drive to save souls took on special meaning when dealing with the mentally disabled, whose souls, it was felt, would be lost without proper religious attention. Similarly, medical thought on mental illness had begun to shift away from treatment of the body alone. The Hartford Retreat for the Insane, chartered in 1822, was a prime example of these shifting attitudes towards insanity.

Hartford Retreat for the Insane, ca. 1850 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

A number of state physicians, including Eli Todd, MD, had led the effort to convince political and community leaders of the need for a facility reflective of emerging medical thought on the treatment of mental illness. The society founded to guide the hospital chose one of its members, Todd, to be the Hartford Retreat’s first superintendent. He served the Retreat from 1823 to 1833, setting the tone of care that prevailed throughout the 19th century. Todd, in fact, represented a generation of transition in mental health.

Dr. Benjamin Rush, one of the young nation’s most respected practitioners, exemplified the older model of understanding insanity as being purely somatic, or bodily, in origin. Rush and the first American physicians treated mental illness much the same as they would any other physical aliment, with a series of bloodletting and purgatives designed to relieve pressure on the brain or remove blockages that offset the body’s humors. (Early medical understanding held that an imbalance of the body’s fluids, such as blood and bile, caused illness.)

Younger physicians, such as Todd, began to perceive insanity as best treated in moral as well as physical ways. Moral treatment emphasized humane care designed to promote a patient’s return to reason. This model had been pioneered in Europe, especially at the York Retreat in England, and first brought to America by the Quakers of the Franklin Retreat of Pennsylvania.

Hartford Retreat Adopts Curative Focus

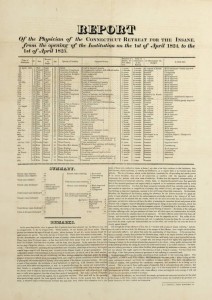

Physician’s report, Hartford Retreat for the Insane, 1825 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

From the time it opened for patients in 1824 to about 1843, the Hartford Retreat was a small, semi-public institution that focused on using a moral curative approach. This included creating a tranquil, kind environment to pacify patients and allow a respite from the hectic pace of the era’s social, political, and economic changes. Caregivers perceived that through conversation, exercise, relaxation, and above all kindness, patients could be soothed into becoming productive members of society once more.

This approach was a precursor to modern psychotherapy and recognized the potential for psychogenetic mental illness. In other words, shifts in medical thought allowed that mental disorders might well be psychological, and not merely physical, in origin. Under superintendants Todd and Amariah Brigham, MD, the Hartford Retreat strove to become a curative, rather than custodial, institution.

In its first 10 years, the Retreat boasted the highest cure rate in the nation and, possibly, the world. Such claims, however, were largely due to the fact that the definition of cured at the time meant a patient had progressed enough to be reintroduced into society; it did not necessarily indicate that a patient’s symptoms had ceased.

Influx of Patients Brings Challenges

By 1843, when superintendant John S. Butler, MD, took control, the Hartford Retreat had already begun to change. Though the emphasis on moral treatment remained in place, the makeup of the patient population had shifted as the number of indigent insane in the state swelled due to the financial panic of 1837.

The number of individuals in Connecticut counted as insane tallied over 700 in 1838, and an increasing number of them were without adequate family care. Though efforts had been made to create a state-wide asylum for the insane poor, the political will was lacking until after the Civil War. In the short term, the Hartford Retreat, the only institution of its kind in the state, was expanded and began a much closer relationship with the state as it began to take state-subsidized insane poor as patients.

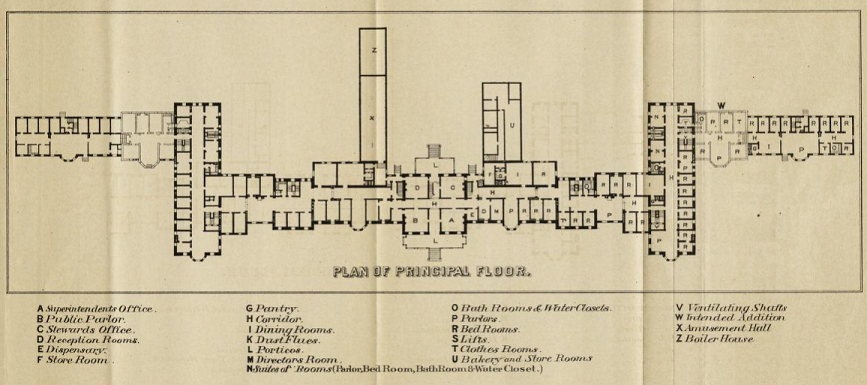

Floor plan, Hartford Retreat for the Insane, 1870

The usual patient at the Hartford Retreat paid roughly $4.00 a week and the stay was relatively short. A significant percentage of the clientele came from well-to-do families and could also afford special amenities like a larger private room and personal attendants. In contrast, the new state-subsidized patients paid $2.50 a week and, on average, stayed for longer periods. This was largely due to the fact that many of the insane poor were suffering from more severe disorders than the more affluent patients.

As the number of subsidized patients grew throughout the 1840s and ‘50s, the character of the Retreat changed, and so, too, did its financial state. The small, upper-class retreat with 50 beds that Eli Todd had known in the 1820s had become a sprawling institution by the time of the Civil War, and its curative focus had been replaced by a more custodial nature, as it housed an increasing number of chronically ill impoverished patients.

Transitioning into the 20th Century

Hartford Retreat for the Insane, East view, ca. 1915-30 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

Butler spent much of his 30 year tenure at the Hartford Retreat trying to keep the facilities in line with Todd’s vision of kind care and tranquil surroundings, despite the institution’s ever worsening financial situation. Through charitable donations and some state aid, Butler was able to institute some recommended changes from Dorothea Dix, the noted mental healthcare reformer who had toured the facility in 1858. The improvements included more wings to ease overcrowding, a boiler to replace dangerous fireplaces throughout the facility, and gas lighting to brighten the halls. In 1860, the Hartford Retreat also hired Hartford native and renowned landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted to re-envision the hospital’s grounds.

The most important change for the Hartford Retreat came in 1868 when the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane opened in Middletown and took in the state’s chronically ill and impoverished insane. Relieved of being the sole institution able to assist this population, the Retreat quickly reverted back to an upper-class, resort-like facility. In the 20th century, the Hartford Retreat incorporated into Hartford Hospital as the Institute of Living and took on a more research-oriented and educational role in the now more advanced mental healthcare field.

Michael Sturges is a social studies teacher at Nonnewaug High School in Woodbury, Connecticut, and a graduate student at Central Connecticut State University.