By Shirley T. Wajda

Created to train men in the skills of farming at a time when agriculture and rural life were feared to be in decline, the Storrs Agricultural College (the precursor to University of Connecticut) also trained women in what was first called domestic science and later home economics.

Women were first admitted to the Storrs Agricultural College in 1893, when Domestic Science was added to the curriculum. In 1899 the institution was renamed the Connecticut Agricultural College. Its 1906-07 Bulletin offers much food for thought about just what higher education was and meant at the turn of the 20th century. For example, “Course No. 7” in Home Economics required courses in English, German, History, Algebra, Geometry, Elocution, and Economics—all part of a liberal arts curriculum. But women students were also required to take courses related to farming: Poultry, Practical Poultry, and Ornithology; Botany, Horticulture, and Forestry; and Meteorology.

And then there were the domestic science courses: Bookkeeping, Sewing and Dressmaking, the wonderfully titled Chemistry of Cleaning, Bacteriology, and, of course, Cooking.

A “Miss Thomas” taught this course:

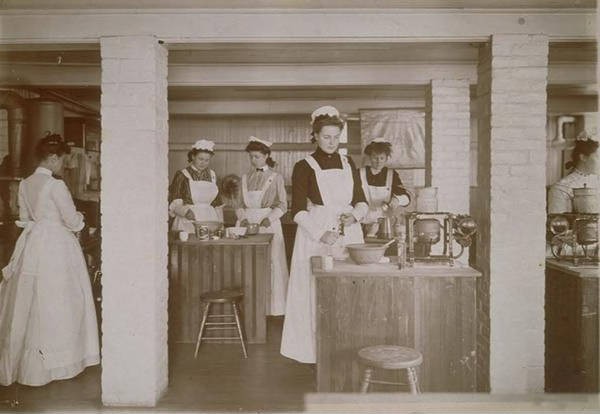

Cooking—This work consists of courses of cookery of a strictly economical character. Correlated with it is a brief study of the composition of foods. The foods cooked are taken up with regard to the food principles they represent. The comparative food and market value and the effect of heat and moisture are noted; also the uses of foods in the body and their digestion and assimilation. The combination of food materials is discussed, especially those most easily obtained upon a farm. The food principles, taken in their natural sequences, are illustrated by the cooking of cereals, vegetables, eggs, meat, fish, peas, and beans. The various methods of making batters and doughs light are discussed. Biscuits, muffins, breads, cakes, and pastry are made. Later comes the more advanced work of salads, desserts, and other made dishes, canning, pickling, and preserving. The economy of material, time, labor, and fuel is brought before the pupil, as are accuracy of measurement, neatness, method, and system.

Cooking class, Connecticut Agricultural College, ca. 1906 – Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries and Connecticut History Online

By the 1920s, the national home economics movement had adopted a more scientific approach to the field, supported by legislation such as the Smith-Lever Act (1914) and state aid to teach home economics, to study food, vitamins, and diet, and to survey and examine health and hygiene among the rural and urban poor. Though many Americans would consider home economics old fashioned, historians agree that the home economics movement provided the means through which women entered higher education.

Shirley T. Wajda, PhD, currently an independent historian living in the Connecticut Western Reserve, is the creator and organizer of Viennapedia, a wiki devoted to the history and culture of her hometown, Vienna, Trumbull County, Ohio.