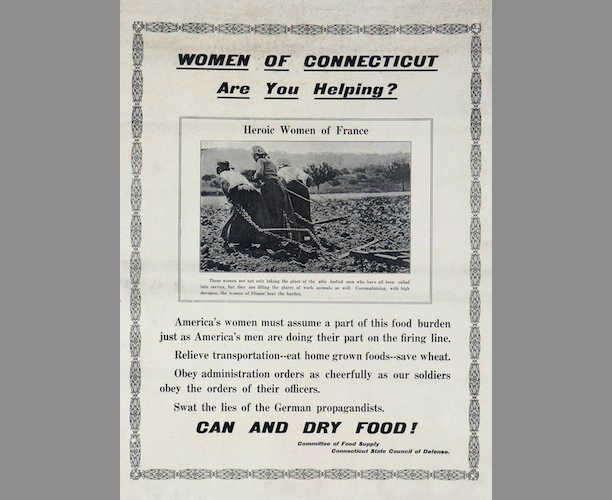

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson started the rallying cry of, “Food Will Win the War,” motivating Americans to increase farm production and reduce household consumption. In the small town of Washington, Connecticut, a group of concerned citizens took up the cause of food production and preservation as a means of contributing to the Allied victory.

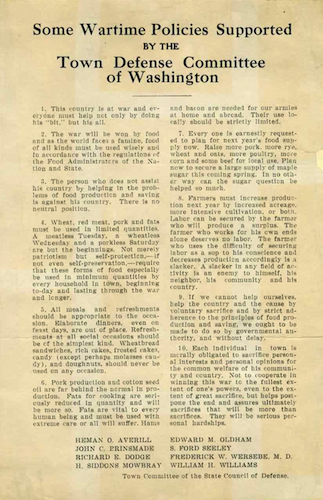

Washington’s Wartime Food Policies Poster, “Some Wartime Policies Supported by the Town Defense Committee of Washington”, from WWI scrapbooks, compiled by Amy C. Kenyon – Gunn Memorial Museum

War Brings Food Shortages

In 1914, Great Britain imported a substantial portion of its food from North America, Australia, Argentina, and Germany. Once at war, Britain became an isolated island surrounded by German U-boats, as the Germans attempted to starve the British people into surrender. This reality, combined with crippling labor shortages in the fields, created a food crisis.

By the winter of 1916, the British people really began to feel the effects of the crisis, as food prices soared, shelves emptied, and hoarding became rampant. The Women’s Land Army of Great Britain formed in early 1917 and sent thousands of women into the fields to produce food, but with diminishing European agricultural production, Great Britain, along with other Allied governments, began relying more heavily on American grain and vegetable imports.

Just weeks after the Women’s Land Army of Great Britain formed, the United States declared war on Germany. Newly increased demand now drove food prices higher in the United States as well. It proved vital that the United States received cooperation from citizens at home to feed the army, the country, and a large part of the European continent.

Washington Moves to Provide Food for Those in Need

In the spring of 1917, the Town of Washington’s representative to the Connecticut Committee on Food Supply, S. Ford Seeley, appointed town residents to the recently formed Food Committee. The committee then formed subcommittees that focused on: the purchase and use of food; livestock and dairying; and food canning and preservation. The goal of these subcommittees was to act in conjunction with local organizations and producers to raise and preserve food products. This mission became even more important with predictions of the food shortage continuing even after the war, as many people in Europe faced rebuilding with little or no provisions.

In March 1918, to offset the local scarcity of farm implements and counter their inflated prices, the Litchfield County Farm Bureau auctioned off used tools, wagons, and machinery for use in food production. Additionally, residents took part in a “Food Show” held in Washington Town Hall which offered practical and useful exhibits on drying and canning produce and saving sugar and flour. The theme of the show was, “Send your food across the water and it will return to you in victory.”

Detail of an article from the Washington, Connecticut, WWI Scrapbook collection, compiled by Amy C. Kenyon, describing the formation of the Farmerettes – Gunn Memorial Museum

The Community Canning Kitchen (created in June of 1918 through the combined efforts of various women’s organizations) helped residents avoid wasteful use of garden products. Under the direction of Alice Carter, work took place one or two days a week in the basement of the Washington Club Hall and capitalized on the surplus produce harvested from large home gardens and the numerous farms surrounding the Washington town green. Volunteers sorted and cleaned donated vegetables and fruits, preparing them for canning by women who took special preservation courses at Storrs College. The Kitchen then sold the food and sent the net proceeds to the Food for France Fund. These efforts eventually yielded 340 quarts of fruit and 349 quarts of vegetables. In addition, volunteers packed 300 pounds of jam into enamel jars and shipped it to a variety of military hospitals, all in effort to make sure Allied soldiers and European citizens did not go hungry.

This article was originally researched and written by Karen A. Stansbury for the Gunn Memorial Museum in Washington, Connecticut, for their exhibit, “Over There: Washington and the Great War.”