By Walter Woodward for Connecticut Explored

In 1973, in a fit of pre-Bicentennial fervor, the state legislature mandated that Connecticut’s license plates should display the state slogan the assembly had adopted 14 years earlier. Since the blue tags with white lettering declaring Connecticut the “Constitution State” were instituted, well over 100 million license plates have proudly proclaimed our state’s special connection to the Constitution.

But which constitution are we referring to? In all likelihood, most people believe this slogan refers to the Constitution of the United States. And indeed, Connecticut did play a crucial role in framing that document. The Connecticut Compromise (providing for proportionate representation in the House of Representatives and equal representation in the Senate) broke the logjam that had stalled acceptance of the Constitution during the 1787 convention.

Source of Connecticut’s Constitution State Claim

Surprisingly, though, the “We, the people” constitution is not the one to which our state slogan refers. Our constitution-the one on which we stake our claim to be “The Constitution State”-is a 1639 document called The Fundamental Orders. It preceded the American constitution by nearly a century and a half and was composed and adopted right here, near the banks of the swift-flowing Hog River (better-known today as the Park River). The Fundamental Orders was the agreement under which the unchartered colony of Connecticut organized its government, and it certainly merits study and commemoration. But was it actually a constitution? Probably not.

For many years popular historians and civic-minded officials did indeed praise the Fundamental Orders, not just as a constitution but as the world’s first democratic constitution. John Fiske, the Hartford-born 19th-century historian whose dramatic and easy-to-read writing style made him the James Michener of his era, called it the first written constitution in history. Not to be outdone, the chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court (1907-1910) Simeon P. Baldwin boldly embellished Fiske’s position. He said that “never had a company of men deliberately met to frame a social compact for immediate use, constituting a new and independent commonwealth, with definite officers, executive and legislative, and prescribed rules and modes of government, until the first planters of Connecticut came together for their great work on January 14th, 1639.”

This is exalted praise, indeed, but even a cursory examination raises questions about both the Fundamental Orders’ uniqueness and its status as a democratic constitution. It was not a democratic innovation; rather, it represented an adaptive improvement of a neighboring colony’s preexisting governing structure.

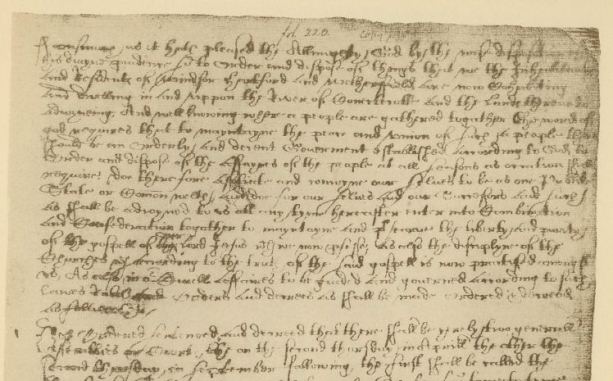

Detail from a facsimile printed in The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, 1934 – Connecticut State Library

Fundamental Orders Looked to Massachusetts for Their Model

The Fundamental Orders document is on display at the Connecticut State Library. It consists of a preamble followed by 11 rules for ordering the colonial government. The conceptual model for the legislative body it set up was the General Court of Massachusetts, the colony from which most of Connecticut’s founders had emigrated. The Bay Colony’s government, framed by the Massachusetts Bay Company’s Charter, had been the subject of chronic dispute between magistrates and freemen over their relative authority. The Orders clearly sought to use but modify the Massachusetts model to avoid such problems. Connecticut put limits on the authority of the governor and modestly expanded the franchise. Whereas Massachusetts only allowed church members to vote for representatives, Connecticut allowed that privilege to all “admitted inhabitants” of a town. In another departure from Massachusetts, Connecticut’s governors were only allowed to serve one-year terms and could not succeed themselves. Furthermore, to avoid election surprises, candidates for governor and the colony’s six ruling magistrates were to be nominated in September but not elected until the following April.

Calling the Fundamental Orders “the first written constitution of modern democracy,” and Hartford, therefore “the birthplace of American democracy,” required jingoistic historians to ignore both the Orders’ derivation from Massachusetts’s governmental model and the fact that Connecticut still barred many people from the franchise. It is not surprising then that former state historian Albert van Dusen called the Orders’ description as a constitution “uncertain,” and Yale Professor Charles M. Andrews rejected the Orders’ “constitutionalism” altogether. For generations of Connecticut residents, however, the belief that the Fundamental Orders (or at least the Connecticut compromise) made ours the Constitution State remains rooted in our psyches and our culture. And that, in a way, could be said to represent Yankee ingenuity at its most creative.

Walter W. Woodward is the Connecticut State Historian.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Hog River Journal (currently Connecticut Explored) Vol. 3/ No. 4, FALL 2005.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.