By Edward T. Howe

By the end of the 18th century, Connecticut had chartered its first five commercial banks, located in each of the five port cities. These banks granted short-term loans, mainly to wholesale merchants and retailers associated with the shipping industry. The loans, by facilitating trading activity, contributed significantly to commercial development in these cities and elsewhere in the state.

Colonial-Era Banking

Neither the Connecticut General Assembly nor elected representatives in other colonies chartered any privately owned commercial banks (i. e., institutions that both accepted deposits and made loans) during the colonial period. When colonists needed loans, borrowers relied upon family, friends, businessmen, and English banks.

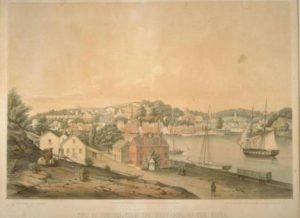

From the 17th through the 18th centuries, agriculture dominated the Connecticut economy, supplemented by shipping activity carried on in the seaports of New Haven and New London and the river ports of Hartford, Middletown, and Norwich. Settled by English colonists between 1633 and 1659, wholesale merchants and retailers in the ports became prosperous over time as their coastal and West Indies trade expanded.

Sarony & Major, View of Norwich, from the west side of the river, 1849, tinted lithograph Fitz Hugh Lane, Gloucester, MA, New York, NY: A. Conant – Mystic Seaport

An attempt to create a private “land bank” occurred in May 1732 when the Connecticut General Assembly chartered a joint stock company known as the New London Society United for Trade and Commerce. This company did not accept deposits but did make loans (through notes or “bills of credit”) secured by the real estate of the borrowers. When spent by the borrowers, the notes were intended to be a commonly accepted means of payment for business transactions. However, critics argued that the note issuance lacked firm support. The General Assembly agreed and dissolved the society in February 1733.

As the governmental needs of the wholesale merchants and retailers increasingly diverged from the farmers living in the larger town areas, residents in the smaller port sections sought a new form of municipality. In 1784 the General Assembly approved all five petitions from the ports to become cities. Local leaders now had the power to enact laws reflective of the needs of the population, which later included banking opportunities.

Meanwhile, Philadelphia merchants, freed from British control over their financial affairs and aware of the need for a banking institution to help finance the Continental army, established the Bank of Pennsylvania in 1780. After Congress ratified the Articles of Confederation in 1781, many investors in the Pennsylvania Bank transferred their subscriptions to help charter the Bank of North America – the first privately owned commercial bank in the United States. The bank, also located in Philadelphia, resolved to stabilize the national paper currency and aid the finances of the central government. To ensure its constitutionality, the Pennsylvania General Assembly chartered the bank in 1782. The bank now had both a national and state charter.

Encouraged by its financial success, other privately owned commercial banks were chartered in New York City in 1784 (The Bank of New York); Boston in 1784 (The Bank of Massachusetts); Baltimore in 1790 (The Bank of Maryland); Providence in 1791 (The Bank of Providence); Portsmouth in 1792 (The New Hampshire Bank); and Albany in 1792 (The Bank of Albany).

The First Connecticut Banks

After observing the financial success of these commercial banks (especially those in Boston and New York City) and the auspicious launch of the First Bank of the United States in 1791, wealthy elites in Connecticut wanted their own commercial banks. In 1792 the Connecticut General Assembly granted charters for privately owned commercial banks in Hartford, New Haven, and New London. The petitioners argued that a bank would facilitate local commercial activity, extend trade beyond the state, provide specie (e.g., gold and silver coins, bars, and bullion) derived from exports for wholesale and emerging retail merchants to buy goods from local sellers, and divert trade going to other ports outside the state. Both the Hartford Bank and Union Bank of New London opened in 1792, but the New Haven Bank did not open until 1796 due to difficulties in meeting its subscriptions through joint stock purchases by investors. Chartered in 1795, the Middletown Bank did not open until 1801 because of yellow and scarlet fever epidemics. The Bank of Norwich received a charter in 1796 and opened that year.

All five of the commercial banks operated in a similar manner. They were open five days a week with morning and afternoon hours (plus half-day on Saturday) to accept deposits and approve “discount” loans (i.e., the principal sum minus the amount of interest owed). The interest rate on the loan was set in the charter at a yearly maximum of six percent. Borrowers received the short-term loans (usually for one to two months) in bank notes for transaction payments. Bank note issuance, in various denominations, was restricted to the combined amount of deposits and capital invested in a given year to control the money supply. Bank trading operations were confined to specie, goods or lands taken from defaulted loans, and bills of exchange (promissory notes binding one party to make a fixed payment to another party). These banks, embraced by their communities, operated profitably in their early years and rewarded their stockholders with consistent dividend payments.

Bridgeport National Bank, 338 Main Street, Bridgeport. The Bridgeport National Bank building was located at the corner of Main Street and Bank Street. It was replaced by the Union Bank building in 1884-1885. – Connecticut Historical Society, Accession number 1983.44.25 0523 img0012.pcd

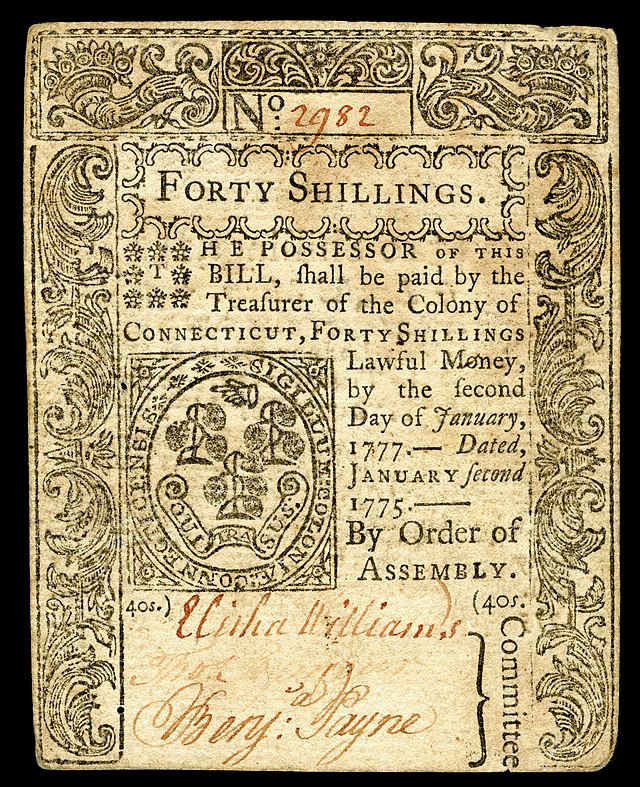

Just prior to opening, the Hartford Bank became the first Connecticut bank to switch from the British monetary system (i.e., pounds, shillings, and pence) to use of the US dollar and its fractional currency, as authorized by the Coinage Act of 1792.

From 1792 to 1802, only private individuals were stockholders in the banks. In 1803 the Connecticut General Assembly accepted offers from the Hartford, Middletown, and New Haven banks to become a stockholder. The General Assembly accepted the offer on condition that it should also apply to the banks in New London and Norwich. Further, for state protection, the state comptroller could require a statement and inspection of the accounts of a bank when it became a stockholder – the initiation of bank supervision in Connecticut.

These five banks were the only commercial banks in the state until 1806 when the Bank of Bridgeport was chartered. Four of these banks survived into the 20th century, in one form or another, when they were absorbed by other financial institutions. The Bank of Norwich, the lone exception, filed for voluntary liquidation under federal bankruptcy laws in 1889.

Edward T. Howe, Ph.D., is Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at Siena College near Albany, N.Y.