By Nancy Finlay

Our ships all in motion

Once whitened the ocean;

They sailed and returned with a cargo.

Now doomed to decay

They have fallen a prey

To Jefferson, worms, and embargo.

– Broadside printed by Isaiah Thomas, 1814

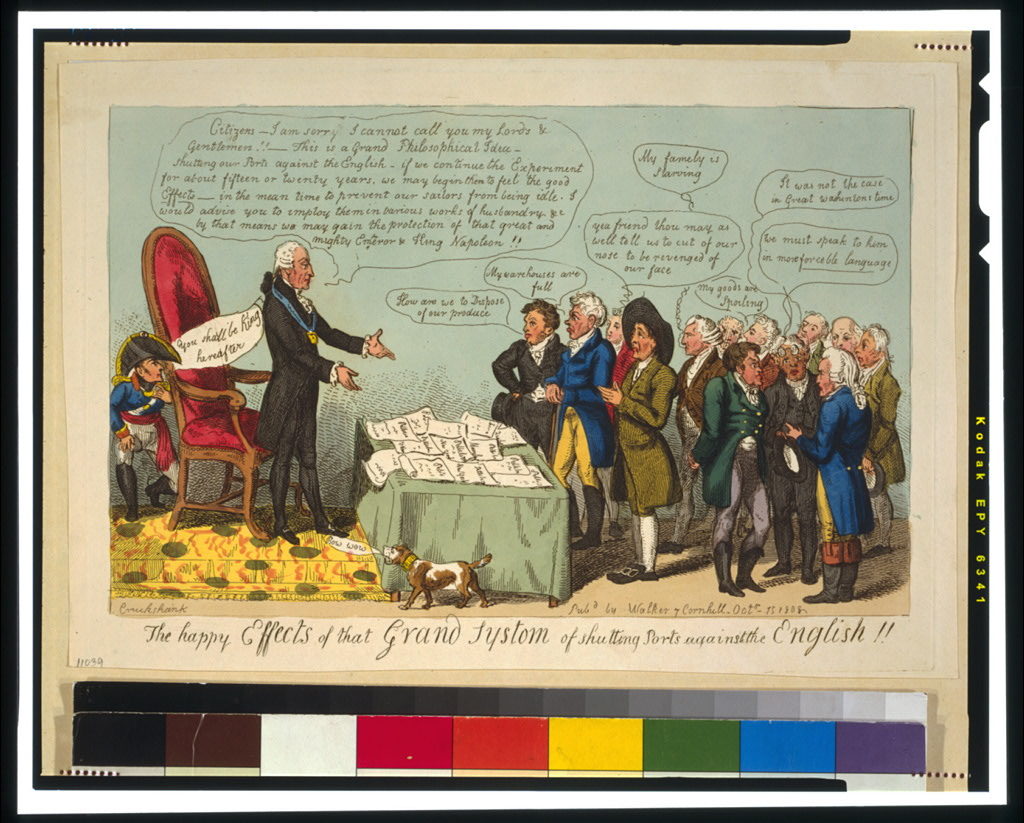

President Thomas Jefferson hoped that the Embargo Act of 1807 would help the United States by demonstrating to Britain and France their dependence on American goods, convincing them to respect American neutrality and stop impressing American seamen. Instead, the act had a devastating effect on American trade. All vessels under United States jurisdiction found themselves prohibited from making foreign voyages. Trade ships sat rotting at the wharves.

Many leaders of Connecticut’s ruling party, the Federalists, made their fortunes in shipping. They had opposed Jefferson from the beginning and considered the embargo both a mistake and a disaster. Some sought to evade the unpopular act, smuggling British goods from Canada using coastal vessels. In open defiance of the law, Jedidiah Huntington, the Federalist customs collector in New London, granted numerous Connecticut vessels “special permission” to make foreign voyages. For its part, Hartford’s Federalist newspaper, the Connecticut Courant, missed no opportunity to attack and condemn the embargo and the Republican party which sought to enforce it.

In February 1809, Governor Jonathan Trumbull Jr. called a special session of the Connecticut legislature and declared the embargo unconstitutional. Trumbull was a staunch Federalist, the son of Jonathan Trumbull Sr., Connecticut’s last colonial governor, who had continued to serve throughout the Revolutionary War. Trumbull Jr. had been governor since 1797, and in 1809 was serving the last of eleven consecutive terms in that office. (He died in office later in the year.) Republican members of the assembly were shocked by Trumbull’s action, calling it “an enormous stride towards treason and civil war.”

An End to the Embargo Act of 1807

The embargo ended in March of 1809, when the Non-Intercourse Act reopened trade to all nations except England and France. The effects of the embargo, however, lasted much longer than that. Connecticut’s Federalists proved adamant in their dislike and distrust of Jefferson and the Republican party. Their opposition extended to the War of 1812 and to the federal government itself, culminating in the Hartford Convention of 1814, ultimately contributing to the Federalists’ downfall.

While the embargo proved a disaster for shipping, it had a positive effect on manufacturing. Connecticut’s many streams and rivers provided a good source of waterpower and textile mills began operating as early as the 1790s, using technology smuggled from Great Britain. These small-scale industries were unable to compete with the large British manufacturers, however, until the embargo shut down trade and British imports were no longer readily available.

Other Connecticut industries also prospered under the embargo. These included paper mills, gun factories, blast furnaces and forges, tanneries, and distilleries. By 1810, Connecticut produced nearly $6 million worth of manufactured goods each year, a substantial sum in that period. The state, which had previously been primarily agricultural, was on its way to becoming a center of industry and innovation.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.