The Naugatuck school system today consists of 11 public schools that provide a thorough contemporary education to over 4,000 students—but this was not always the case. The pride Connecticut residents have taken in their education system was not something easily achieved. For centuries, education took a backseat to the demand for child labor and the needs of families to supplement their incomes. In Naugatuck, the rich industrial base provided ample opportunities for children to join the labor force.

In 1650, Connecticut passed the “Act for Educating Children.” The writers of this legislation intended it to ensure that children could read and comprehend the laws Connecticut expected them to live by. Over the next two centuries, Connecticut passed a number of loosely enforced education laws that penalized parents financially for a child’s poor school attendance. Even though regulations on child labor were in place by the mid-19th century, Connecticut residents seemed indifferent to their enforcement.

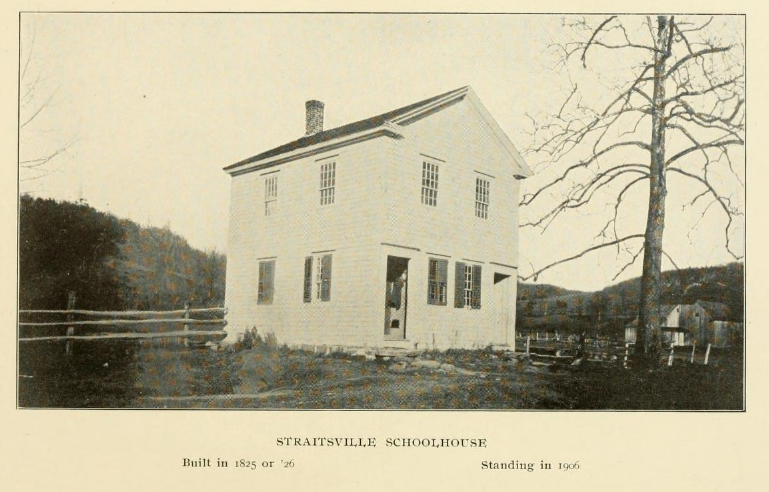

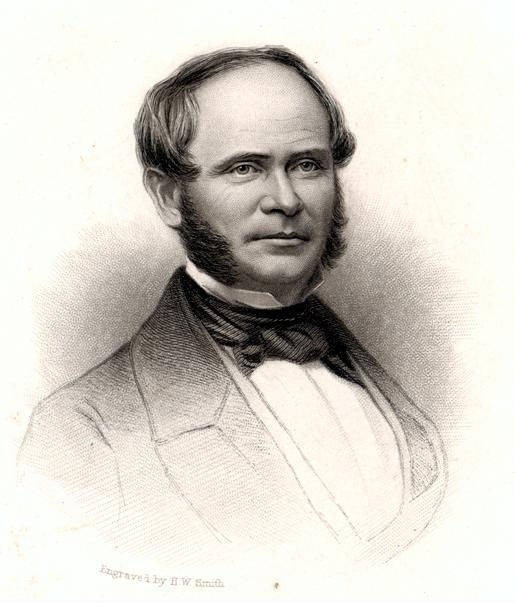

In Naugatuck in 1850, concern over the quality of education offered to children caused S.W. Kellogg, a young lawyer on the Naugatuck Board of School Visitors, to reach out to the State Superintendent of Schools for help. This superintendent was Henry Barnard, a renowned educational reformer, who suggested consolidating Naugatuck’s numerous school districts into the Union Center School District, consisting of a new graded school and the town’s first high school.

Unfortunately for Kellogg and Barnard, however, the lure of industry in Naugatuck took a serious toll on school attendance. In 1863, less than half of the children in town actually attended school. The boom in industry that coincided with the start of the Civil War only dropped those numbers lower, and by 1873, Naugatuck ranked 131st in school attendance among Connecticut’s towns. It took changes to state laws and a shift in hiring practices to reverse this trend.

After 1869, enforcement of state labor laws was more centralized. An 1871 law made children attend school even if they had unemployed parents, and by 1880 children under the age of 14 needed signed certificates of attendance from their teachers in order to be eligible for most forms of employment. These laws coincided with a lower demand for child labor at the start of the 20th century. This is often attributed to an increasingly mechanized workplace that allowed for the deskilling of adult labor. Combined with stricter enforcement of the laws, this change in labor demand initiated the transition of large groups of children back into the school system and made regular school attendance the standard for Connecticut’s youth in the decades that followed.