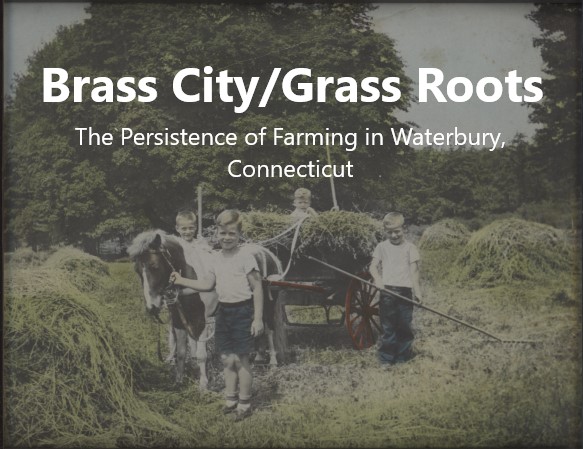

This article is part of the digital exhibit Brass City/Grass Roots: The Persistence of Farming in Waterbury, Connecticut. Use the arrows at the bottom of the page to navigate to other parts of the exhibit.

“We walked all over the city [and] we learned how everybody gardened.”

—Nick Coscia

At Brookside Farm, inmates were expected to earn their keep and offset the costs of running their facility by producing the food they ate and a surplus to sell. Municipal reports from the early 20th century show the farm raising pigs, chickens, and cows as well as a large variety of fruits and vegetables, click to enlarge

Even in the recent past, food-growing was woven into Waterbury’s civic fabric. In the early 20th century, for example, the Department of Education employed an agriculture teacher who got students planting gardens near their schools. The city had many Liberty Gardens during World War I and Victory Gardens during World War II, encouraged and aided not just by local government but also by the large brass factories.

Like many cities, Waterbury established a town farm, a residence and workhouse with land for the homeless poor, “minor” criminals and those labelled “insane.” In the 1820s, the city contracted out this responsibility to a local farmer, Daniel Scott of Bunker Hill. In 1839, the town purchased a farm and its buildings from another Bunker Hill resident, Joseph Bronson, to serve as the official almshouse, house of correction, and town farm. The Brookside Home, which outgrew its original wooden structures and was replaced by a large brick building in 1893, stayed open until the 1960s, though it is unclear how long the farming operation itself lasted.

While few 20th-century Waterbury residents were dedicated farmers, many had huge vegetable gardens and animals they raised for meat, milk, and eggs. Families worked together to cultivate these gardens and tend livestock. By the late fall, thousands of Waterbury cellars were always full of cabbages, onions, turnips, apples, Mason jars of vegetables, fruits, and sauces, crocks of pickles and sauerkraut, hanging sausages and cheeses, as well as barrels and jugs of homemade wine or beer.

Tony Dellorfano stands in his large garden, on a plot of land that used to be part of his father’s Buck’s Hill farm – Photo courtesy of Georgia Sheron, click to enlarge

Residents had livestock not only in outlying districts of the city, but in some of its most urban areas. Well into the 20th century many people in Waterbury raised their own chickens and rabbits, and might even have a goat, a cow, or a pig or two. Aldermanic records show residents asking the city to reimburse them for poultry killed by stray dogs. Municipal records also show that every year a number of residents petitioned the city for permission to put up barns, stables, and chicken houses on their property; while tenement dwellers frequently had their animals confiscated by building inspectors.

Local food production often intimately coexisted with industry. Antonio Gucciardi loved being on third shift at Chase Brass because it gave him time in the day to work his “farm.” He and his family lived on Highland Avenue, still an uncompleted road in the 1930s with much undeveloped land nearby. In back of the Gucciardi house was a 50-foot rabbit hutch, chicken houses, and a pig and a goat. The Gucciardis also had a 3-acre plot for vegetables and a little stand in front of the driveway where they sold their eggs, chickens, rabbits, and vegetables. Near where Hans Rasmussen and his neighbors ran their dairy operations a generation earlier, plots such as the Gucciardis’ were common before the frantic building of the post-World War Two era.

Farm or garden produce could mean more than subsistence or a cash supplement to another job; it could be a form of alternative currency. Nick Coscia claims, “We probably had the largest garden in Brooklyn [a Waterbury neighborhood]. It was roughly forty by sixty [feet], maybe a little longer.” Coscia’s father taught Nick and his brother to supplement the soil with manure, leaves, and yard wastes from their neighbors and farms and estates in nearby towns. Even the ash floating in from nearby factories was considered a boon to the earth. The resulting soil “was so nutrient-rich, it was almost black.”

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>