This article is part of the digital exhibit Brass City/Grass Roots: The Persistence of Farming in Waterbury, Connecticut. Use the arrows at the bottom of the page to navigate to other parts of the exhibit.

During the 1870s and 1880s, when dozens of brass factories and clock shops were already roaring away in Waterbury, there were still close to 200 people officially inscribed as farmers in censuses and city directories. There were also many listed with other professions who still ran farms.

Brown’s Meadow Farm, circa 1900 – Photo courtesy of the Collection of the Mattatuck Museum, click to enlarge

Waterbury’s farms were still owned mainly by Yankee descendants of the city’s original 17th-century proprietors or others who came during the 18th century. Most farms at this time ranged from 10 to 250 acres. No one grew wheat, which in this region had long ago succumbed to disease and competition from the large grain farms of the Midwest. Instead, corn and hay were commonly grown for animal feed as well as large quantities of potatoes and “orchard produce”: apples, followed by peaches and pears, cherries and berries. About a quarter cultivated “produce for market gardens,” meaning they were selling some of their vegetables. Nearly all had dairy cows, oxen, and “cattle” (probably cows raised for meat) and pigs. Most had hundreds of gallons of milk to show for a year’s worth of work, but at that time it was mostly sold as butter and cheese. Milk was difficult to keep fresh and disease free—it was not then the everyday household beverage it became in the 20th century.

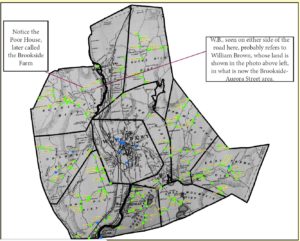

Green dots represent farms. Blue dots represent farm-related occupations, including sale of agricultural implements, grain, feed, flour, and fertilizers, wholesale meat and produce, milk, and processing of hides, tallow, and bone meal. The blue dot at the very bottom of the map represents Platt’s Mills grain operation started by Alfred Platt and Oliver Camp – Map courtesy of David Perrier, click to enlarge

Old maps tell us much about the numerous men and women farming or processing food in Connecticut in the late 19th and early 20th century. This 1874 map of Waterbury shows the names of the city’s property owners, divided into nine distinct districts surrounding downtown.

As you look at this map, notice the names of the districts—which ones are the names of current neighborhoods? Which ones have dropped out of usage, and why do you think that happened?

Which people’s names are familiar to you as the names of streets? Are the current streets near where the farms were?

How many women farmers can you find?

How many farmers can you find who are possibly of ethnic backgrounds other than Yankee or British?

Centre District

The Porters were one of the first families in Waterbury, and many of their members persisted as farmers. A biography of one Porter shows how some city residents supplemented farming with other activities, including the industrial ones that had supposedly made farming obsolete:

“Deacon Timothy Porter was one of the prominent and successful farmers and manufacturers of Waterbury, in his day. Although agriculture was his chief occupation, he was active and busy in various lines. In early life he worked on a farm through the summer season and taught school in the winters. After his marriage he purchased property. Being very thrifty he ran a carding machine and prospered in the business. Selling his machine in 1829, he for twenty years thereafter carried on the business of brickmaking, supplying during that period about all the brick used in Waterbury. In 1845 he was instrumental in establishing a brass mill on his property—owning a fine water power on Mad river—which became the East Mill of the Waterbury Brass Co. ”

—Joseph Anderson, D.D. from The Town and City of Waterbury, Connecticut, From the Aboriginal Period to the Year Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Five, Vol. III, 1896

Horse Pasture District

The Nichols had come to Waterbury in 1728 and spawned generations of farmers. Joseph N. Nichols “owned the homestead farm at Hopeville and also the large Hull farm on Town Plot, Waterbury, upon which he made many improvements” [Commemorative Biographical Record of New Haven County, Connecticut, 1902] Sometime after Nichols’ death four years after this map was published, and before 1902, his Town Plot land was turned into building lots.

Franklin Potter, “a successful farmer and market gardener of Waterbury, is a native of that town, born on the old Potter homestead in what is now Hopeville” in 1826. The land had at one time been known as Brocket Hill after an earlier settler who had purchased the land from Native Americans. Franklin Potter was a button maker for some 25 years, but “since retirement he has given his entire time and attention to farming and market gardening on the old homestead at Pearl Lake.” [Commemorative Biographical Record of New Haven County, Connecticut, 1902]

East Mountain District

The Hotchkiss family of England came to Connecticut in the 1600s. C. B. Hotchkiss, “[a]t the age of fourteen years…went to Union Mills, Ind[iana]., where he engaged in farming until 1856, when he disposed of his interests there and returned to Waterbury, Conn. He located on the Stephen Hotchkiss farm, where for the past forty-five years, he has successfully engaged in dairy farming and stock raising.”

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>