This article is part of the digital exhibit Brass City/Grass Roots: The Persistence of Farming in Waterbury, Connecticut. Use the arrows at the bottom of the page to navigate to other parts of the exhibit.

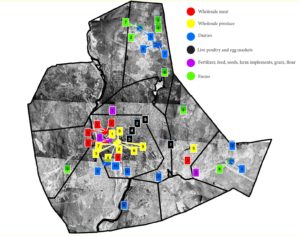

In the 1960s, some farms and food processing/marketing businesses remained but they were in definite decline compared to earlier years – Map courtesy of David Perrier, click to enlarge

Local food production was part of Waterbury daily life until fairly recently. City residents expected locally available fresh eggs, meat, milk, and vegetables. Not until after World War II did most become increasingly distanced from their food sources, for a range of reasons:

- National, state, and local laws increasingly regulated the production of milk and other foodstuffs. By the end of the 1800s city law required all milk vendors to be licensed, and milk and cows to be inspected. By the 1920s milk had to be bottled rather than sold from open cans, and pasteurization became the norm. Such regulations were a boon to consumers, reducing high infant mortality rates and other public health problems. However, they were often a burden to producers.

- The city also became active in supervising the raising and slaughtering of live animals. By 1902, city ordinances specified that all households with farm animals had to pen and license them. With growing population density, the city became stricter in enforcing “nuisance” laws, revoking licenses when smells, improper disposal of manure, or noisy animals posed a problem for neighbors. In 1972, the city restricted farm animals to those with one acre or more, and so drastically limited most city residents’ ability to raise their own meat, milk, or eggs.

- Farmers in Waterbury and the larger region had been struggling for centuries, constantly retooling as markets changed. Connecticut had become strongest, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in poultry, eggs, dairy, vegetables, feed and sweet corn, and small fruit, apple, and peach cultivation. But where new technology worked for the Pierponts and other farmers before World War II, it began to work against them in the post-War era. Increased efficiency of production meant, paradoxically, overproduction leading to lower prices for farm products.

- Developments such as refrigerated train cars and trucks undercut the advantages of fresh and local farm products, with faraway produce sold at cheaper prices.

- The fossil-fuel-based agriculture of the modern period has been a boon for farms much larger in scale than those in New England, with inputs and machinery much too expensive for most small farmers. Federal farm subsidies generally went to large farmers as well.

- In an increasingly urbanizing world with other careers readily visible, farm children usually opted out of the all-consuming farming life that depended on whole families working together. Farming for children meant getting up at 4 in the morning to milk, feed, and water the cows, as well as having chores after school and on weekends.

- The pressures of development had a huge effect on local farming, accelerating after World War II. Farmers increasingly sold out to developers who could offer more for their land than could be made farming it, and with the children not interested anymore, it was a no-brainer. Developers liked working with farmland, as it had already been “improved,” that is, cleared of rocks and trees and often leveled.

- Public development was also a factor. The Pierponts’ centuries-long dairy operation ceased when the city took their East End farmland in the 1970s to build an elementary/middle school/high school complex. The Gagliardi family of Bucks’ Hill faced the same problem when their land was taken for another school complex to serve the North End of town.

- The suburban-style development and increasing population density that brought new schools to the outskirt neighborhoods of Waterbury also inhibited farmers who were still active. The Becces, for example, felt the pinch in the 1970s as the land around them was made into housing developments. Neighbors complained that the smell of the pigs was ruining their quality of life.

- The commercialization of food production also hastened the decline of local production and marketing. Charlie Antonelli’s butchers were no longer needed with the advent of pre-cut, cryogenically packaged meat from national conglomerates. The DeLaurentises could not compete with the growing trend of consumers doing all their shopping at supermarkets, and closed up their live poultry store in 1959.

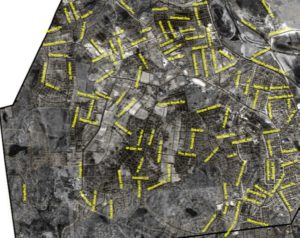

The pressures to develop farmland into house parcels were strong in urban areas like Waterbury. The map below of a portion of Bunker Hill shows aerial photos from 1934 overlaid with modern streets and parcels. If you look closely, you can see fields, forests, and orchards (areas that appear to have a dotted pattern are actually regular rows of evenly-spaced trees) that have been carved into suburban-style developments.

It is likely that the rise of food conglomerates also caused the decline of local government supports for Waterbury’s food production. If farms were disappearing and people were getting their produce at supermarkets courtesy of California growers, why should the city manage a farmers’ market? If meat was being trucked in from afar, why have a local slaughterhouse?

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>