By Emma Wiley

Ann Petry was the first African American woman to sell over one million copies of a book with her first novel, The Street. Living most of her life in Old Saybrook, Petry explored the intricacies of Black life during the mid-20th century with her writing.

Growing Up in Old Saybrook

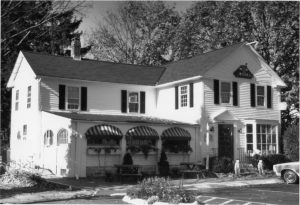

Anna Houston Lane was born in 1908 in the apartment attached to her family’s pharmacy in Old Saybrook. She was the third daughter of Peter Clark Lane, a pharmacist, and Bertha James Lane, an entrepreneur and chiropodist (treatment of foot ailments).

While Connecticut did not institute stringent Jim Crow segregation, racism and the treatment of Black people affected Petry’s adolescence and informed her future writing. At times, Petry faced racist teachers and neighbors. In fact, Petry’s father wrote a letter to The Crisis—the NAACP-published magazine—about how Old Saybrook teachers refused to treat his daughters equally to white students. Later, Petry recycled many of these personal experiences in her stories and novels.

Petry graduated from Old Saybrook High School and spent over a year at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia. She decided to return to Connecticut, however, and transfer to the Connecticut College of Pharmacy. Following in the family practice, Petry earned her pharmaceutical degree in 1931. After graduation, she worked in her family’s businesses, including helping her aunt, Anna Louise James, aka “Miss James,”—the first woman pharmacist in Connecticut.

On February 22, 1938, Anna Houston Lane married George David Petry in her parents living room. Two years earlier, however, the couple secretly married in Mount Vernon, New York—a secret that their only daughter, Elisabeth Petry, did not discover until after her mother’s death. The couple moved to New York City, finding a home in Harlem in 1938.

Petry’s Writing Career

After moving to Harlem, Petry began to write for local Black newspapers—first the Amsterdam News in 1939, then The People’s Voice. To hone her craft, Petry also attended the renowned author Mabel Louise Robinson’s advanced fiction writing workshops at Columbia University.

The Crisis published her first short story, “On Saturday the Siren Sounds at Noon,” in their December 1943 issue. Later, the literary community realized that The Afro American actually published the first Petry writing in 1939—a short story titled “Marie of the Cabin Club,” under the pen name “Arnold Petri.” Petry published the rest of her work under her own name, but dropped the “a” from the end of her first name and went by “Ann.”

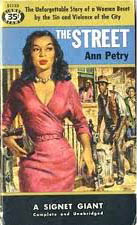

Petry attracted the attention of the publisher Houghton Mifflin and in 1945 she received a Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship to complete her first novel. Petry finished The Street—a novel about a single Black mother in Harlem during WWII—in 1946. It was met with great success and became a bestseller—the first book by an African American woman to sell over a million copies. Literary critics often put Petry’s The Street in conversation with other famous works such as Richard Wright’s Native Son, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, and James Baldwin’s work. According to scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin, “through [Petry’s] fiction, she sought, time and again, to demonstrate the high social costs of the most fundamental paradox of American democracy: its treatment of its black citizens.” Petry carved an essential place in literature for Black women’s unique experiences of the mid-20th century.

Houghton Mifflin also published Petry’s subsequent novels—Country Place in 1947 and The Narrows in 1953. In addition to her novels, Petry wrote numerous short stories and several books for children, including a biography of Harriet Tubman. Outside of her traditional writing, Columbia Pictures hired Petry in 1957 to write the screenplay for a film, That Hill Girl, starring Kim Novak, but the film never materialized.

Petry disliked the sudden fame and attention she received from her literary success and often avoided the spotlight, carefully selecting interviews and event appearances. According to her daughter, Elisabeth, Petry protected her privacy and life, “[tailoring] the story of her own life by omitting information, changing details, embellishing the stories she heard as a child.” For example, partially due to a documentation error and the efforts of Petry herself, she reported various birthdates and years. To further control her legacy, Petry destroyed many of her own journals and papers.

In part to live a quieter life, the Petrys moved back to Old Saybrook in 1947, after George returned from serving in the military during WWII. Petry remained in Old Saybrook for the rest of her life except for a brief stint in Hawaii during the mid-1970s when she served as a visiting professor of English at the University of Hawaii.

Petry in her Community

From her time in Harlem to Old Saybrook, Ann Petry was involved in her community in numerous ways—from education to politics to her church. She served on the Board of Education and League of Women Voters in Old Saybrook. Petry was very concerned with the racism that she experienced as a child in Old Saybrook and was determined not to allow it to repeat. When her daughter was in school, Petry stopped a local English teacher from attempting to have white students wear blackface in the high school play and she often monitored the content of history books at the school.

While in Harlem and working for The People’s Voice, Petry became acquainted with numerous political and labor activists, such as Dollie Robinson and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. With Robinson, Petry co-founded Negro Women Incorporated, which was a consumers rights group for Black women affiliated with Powell Jr.’s People’s Committee. Several of the people Petry associated with during her time in Harlem were later monitored for communist sympathies, but Petry largely escaped suspicion. Apart from her political activism in Harlem, Petry was also a member of the American Negro Theater and appeared as Tillie Petunia in a production of On Striver’s Row.

In her spare time, Petry enjoyed collecting antiques and books, amassing a significant collection, including an 1894 edition of Venture Smith’s autobiography and an estate auction booklet from Madame C. J. Walker’s home (the first Black woman billionaire). Petry also kept numerous objects from James Pharmacy after the death of her aunt Anna Louise James, including medicinal bottles.

Ann Petry’s Legacy

In 1992—within the last few years of Petry’s life—Houghton Mifflin republished The Street, renewing excitement for Petry’s work and her impact on literature. A few years later, in 1994, Petry was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame and the Department of the Interior listed the pharmacy building where she was born on the National Register of Historic Places. Petry died on April 28, 1997 at age 88—over 50 years after publishing her first novel.

Due to her dislike of fame, Petry refused to allow anyone to write her biography while she was alive. In 2009, her daughter, Elisabeth Petry, published a biography of her mother entitled At Home Inside: A Daughter’s Tribute to Ann Petry. Elisabeth has also published another book, Can Anything Beat White? A Black Family’s Letters, and numerous articles about the Lane and James families. Ann Petry’s groundbreaking work continues to inspire future generations of writers—in Connecticut and beyond.

Emma Wiley is the Digital Humanities Assistant at CT Humanities and holds a B.A. in History from Vassar College.