Effects of Revolution

Lists of candidates for the Upper House before and after the Revolution show how little effect the war had on Connecticut’s political leadership. Many of these men stayed in office for decades thereafter.

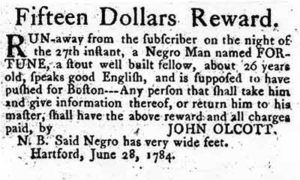

Reward posted for capture of a runaway slave

Half of Connecticut’s 5,500 African Americans were still in slavery as the Revolution ended. Connecticut did little to extend the Revolution’s ideal of liberty to African Americans. In May 1784, the General Assembly voted to support the abolition of slavery, but concern for “property rights” led them to limit emancipation to slave children, and then only after they reached the age of 25.

By 1790, the General Assembly had grown to 200 members and a more substantial facility was necessary. A new Hartford State House was completed in 1796.

In 1806, the General Assembly established a separate Supreme Court. The legislature continued to grant divorces and remained a final court of appeals until 1818.

The Constitution of 1818

A new Hartford State House

The Constitution of 1818 formed the basis of Connecticut government for the next 147 years. It ended state support for the Congregational Church and further strengthened the separation of powers by establishing an independent court system. It renamed the Upper House the Senate, created the office of the Senate President Pro Tempore, and mandated one Assembly session a year, alternating between Hartford and New Haven. At the same time, it retained Connecticut’s unusual system of town-based representation, a decision that would increasingly limit the General Assembly’s ability to govern effectively as the century wore on, and it excluded African Americans, Native Americans, and women as voters by explicitly limiting the franchise to white males.

This article is a panel reproduction from An Orderly and Decent Government, an exhibition on the history of representative government in Connecticut developed by Connecticut Humanities and put on display in the Capitol concourse of the Legislative Office Building, Hartford, Connecticut.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>