The story of the Foreign Mission School connects the town of Cornwall, Connecticut, to a larger, national religious fervor that preoccupied the United States during the Second Great Awakening. This Christian revival movement emerged in the early 1800s and many who embraced it saw religion—especially through the work of missionaries—as a tool for civilizing “heathen” peoples. Cornwall’s Foreign Mission School exemplified evangelical efforts to recruit young men from indigenous cultures around the world, convert them to Christianity, educate them, and train them to become preachers, health workers, translators, and teachers back in their native lands.

Educating a New Generation of Missionaries

Henry Obookiah (Opukaha’ia) – New York Public Library Digital Gallery

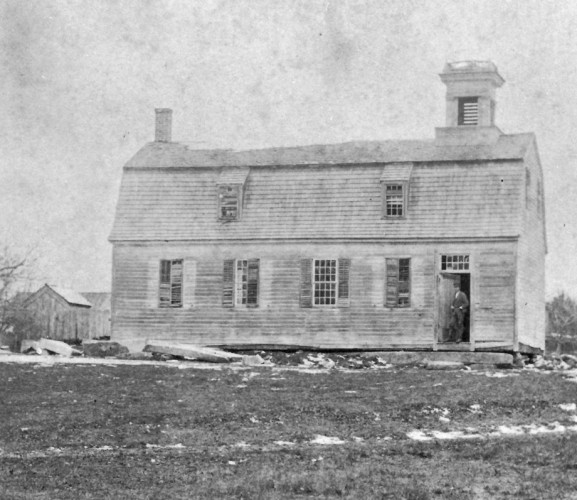

The school’s first student was a Hawaiian refugee named Heneri Opukaha’ia. (His name is often anglicized as Henry Obookiah.) He’d come to the US after spending time as a cabin boy aboard a trading vessel, and it was the ship’s captain who brought 18-year-old Opukaha’ia to New Haven in the winter of 1810. Shortly thereafter, Opukaha’ia is reported to have been befriended by Edwin Dwight, the son of Yale president Timothy Dwight, who found him weeping on the steps of the Yale chapel, lamenting his lack of education. The senior Dwight and a number of other ministers expressed concern for the plight of Opukaha’ia. They took him into their homes, where he learned English and proved to be an adept scholar and enthusiastic Christian convert. The desire to provide for the education of Opukaha’ia dovetailed with a new movement to train members of indigenous communities to serve as Christian missionaries to their own people—rather than send Anglo-Americans, as had been the norm. As a result, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions opened the Foreign Mission School in 1817 in what is now Cornwall Village. In its first year, the Foreign Mission School had 12 students, more than half of whom were Hawaiian. The next year, the enrollment doubled to 24 and, in addition to Chinese, Hindu, and Bengali students, also consisted of seven Native Americans of Choctaw, Abnaki, and Cherokee descent. By 1820, Native Americans from six different tribes made up half of the school’s students. Once enrolled, students spent seven hours a day in study. Subjects included chemistry, geography, calculus, and theology, as well as Greek, French, and Latin. They were also taught special skills like coopering (the making of barrels and other storage casks), blacksmithing, navigation, and surveying. When not in class, students attended mandatory church and prayer sessions and also worked on making improvements to the school’s lands.

Diversity Stirs Prejudices

The introduction of students from so many diverse cultures into an environment with a rich Anglo-Saxon and Puritan history was not without its controversies. Local residents were wary of having largely dark-skinned, non-Christian individuals living among them. Many of these concerns involved fears of miscegenation, a term used to describe a mixing of the races. Romances that evolved between two students and two local residents provided a ready outlet for a violent expression of these fears. In 1824, John Ridge, a student at the Foreign Mission School and the son of a Cherokee leader, began a courtship with Sarah Northrop, the white daughter of the school’s steward. A year later they married. After the ceremony, the couple hurried into a coach for protection from an incensed local citizenry and, as they journeyed to Cherokee territory in present-day Georgia, they faced angry mobs of people during the entire length of their trip. A year later, another Foreign Mission School student, Elias Boudinot (John Ridge’s cousin), fell in love with a young Cornwall girl named Harriet Gold. Despite protests from Harriet’s family and the local clergy, the two became engaged. Once the announcement was made public, Boudinot and Gold had to seek refuge at Harriet’s parents’ house to avoid angry local citizens. On the town green, Harriet’s own brother set an effigy of his sister on fire. Despite all of this, Harriet and Elias married in 1826.

Elias Boudinot

School Closure

The outrage that these two marriages caused among the local populace led to significant pressure to close the school. In addition, the families of some students grew concerned that the New England climate was harming the health of their children. The “climate-related” deaths of three students from islands in the Pacific only exacerbated this fear. Opukaha’ia himself did not live to become a missionary; he died in Cornwall, just one year after his arrival at the school, at the age of 26. These concerns, along with other factors such as the expense of such educational undertakings and failing enthusiasm for the prospects of indigenous missionaries, led the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to close the school in 1826. During its brief existence, Cornwall’s Foreign Mission School taught over 100 students. More importantly, however, it connected a small town in Connecticut to larger, international events, such as the flourishing Christian missionary movement. Additionally, it reveals the boundaries of tolerance in the early 1800s.