By Nancy Finlay

The Native Americans who lived along the shores of (what became) Milford, Connecticut, named a prominent nearby island “Poquahaug” or “Eaguahaug,” probably meaning “cleared land.” Other people later referred to it as Milford Island or Allen Island, but in 1657 the land was provisionally granted to a man named Charles Deal for use as a tobacco plantation and this likely provided it with its most commonly used moniker, Charles Island.

Charles Island Becomes a Summer Resort

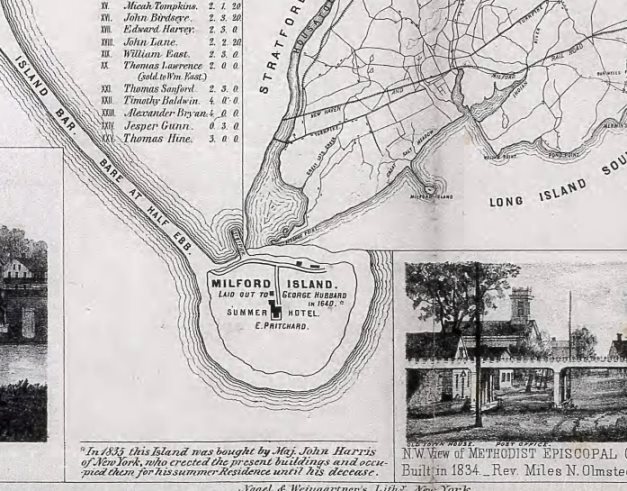

Detail of Milford Island from Map of Milford, Connecticut by E. R. Lambert, 1855 – Connecticut Historical Society

In the early 1850s, the island became the property of Elizur E. Pritchard, a Waterbury manufacturer, and by 1855 the lone house on the island became a summer resort hotel. The hotel rested in the middle of the island, about 50 feet above low-tide level, and lay surrounded by cherry trees, a lovely garden, and green lawns. A series of proprietors and superintendents subsequently touted its charms, including “its beautiful location . . . delightful scenery, and its advantages for fishing, bathing, and boating.” (A bowling alley, bar, and rooms for young men operated in a separate building at the foot of the hill below the main house, so that any rowdy activities did not disturb the other guests.)

In addition to its lovely scenery, a further advantage of the hotel’s location was its ease of access. At low tide, a causeway negotiable by carriages and wagons connected it to the mainland. Visitors arriving by train had the option of reaching the hotel either by carriage or by boat. Excursion steamboats from New Haven also called at the island allowing day trippers from as far away as Hartford to spend a summer day on Long Island Sound, perhaps taking in an “old-fashioned clambake” before returning home.

Elizur Pritchard died very suddenly in November 1860 (probably of a heart attack brought on by exertion) as he was rushing to get off the island before high tide. The island then became the property of his unmarried daughter, Sarah, who continued to operate it as a resort. By 1866, the hotel boasted a swimming pool, fountain, and an aquarium (said to be the largest in the country) and was described as a “good spot and a healthy place.”

From Fertilizer and Fights to Silver Sands State Park

But the days of Charles Island’s service as a trendy resort location were short-lived. In the years following the Civil War, Charles Island’s reputation as a wholesome family resort began to decline and the hotel closed. By 1868, a fertilizer factory on the island produced a prodigious stench that led to complaints from residents on the mainland. In April 1870, Governor Jewell needed to call out the state militia to break up two prizefights on the island that had attracted a “large party of roughs” who arrived by steamboat from New York City. The resort buildings succumbed to fire in the 1880s, around the same time the fertilizer plant shut down.

Tombolo to Charles Island, Silver Sands State Park, Milford, Connecticut. Photograph by User: Adavyd on Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA 3.0)

In the years that followed, the island remained largely uninhabited, but still managed to host the occasional visitor. In 1893, two fishermen became stranded there and had to be rescued when the tide came in and caught them off guard. Then, in 1903, four campers found themselves “storm-bound and starving” on the island and also required rescue.

Meanwhile, numerous plans for the island came and went. In 1904, developers considered Charles Island as a possible site for an amusement park (one of the suburban “trolley parks” popular in that era) but the project never came to fruition. Then, with America’s entry into World War I in 1917, rumors emerged that the United States government planned to erect a “powerful wireless station” there and fortify Charles Island to protect Bridgeport and neighboring towns from enemy submarines.

Eventually the State of Connecticut acquired the island and opened it as part of Silver Sands State Park in 1960. Today, Charles Island is maintained by the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and is the site of a large heron and egret rookery.

Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society.