By Donald L. Malcarne and Brenda Milkofsky

A mid-nineteenth-century catalog cover from the ivory business of Julius Pratt – Deep River Historical Society, Ivoryton Library Association and the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries

At one time, manufacturing facilities in the lower Connecticut River Valley town of Deep River and the village of Ivoryton in Essex processed up to 90 percent of the ivory imported into the United States. Ivory, a dentine of exceptional hardness that composes the main part of the tusks of the elephant, walrus, and other animals, had for centuries been a prized natural resource. Used mostly for carving and ornamental purposes, its unique strength and beauty made it an ideal material for such goods as combs—and Connecticut entrepreneurs were not slow to recognize its potential. As trade between eastern Africa and the United States, England, and the Netherlands expanded during the first part of the 1800s, ivory became readily available. This development, and its effect on the local area, became an important part of the Industrial Revolution in the United States.

Combs and Comb-making

The ivory trade’s transformation of the lower Connecticut River Valley all started with hair combs. In the late 1700s, craftsmen made combs primarily out of cow or ox horn cut and fashioned by hand. This limited production and created a relatively expensive grooming tool. In 1798, silversmith and Congregational church deacon Phineas Pratt, who made the clockwork timer for David Bushnell’s submarine, Turtle, invented a device that allowed for the mechanical cutting of combs. This sped production and lowered costs—and demand for combs, an essential article of human hygiene, rose quickly.

The comb-making business centered along the Falls River, where Phineas Pratt owned land, and the Deep River in Potapoug (the Native American name for the area that became known as Deep River and Ivoryton). Prior to 1810, Ezra Williams established a comb-making shop at his father’s shipbuilding yard at the mouth of the Falls River and soon moved it to Deep River, where it became the largest of its kind in the country. George A. Read, another ivory pioneer, partnered with Williams and carried on the business after Williams’s death in late 1818.

Piano Keys and the Demand for Ivory

The start of the Industrial Revolution in the United States coincided with the advent of widely available popular sheet music. And, as playing music became a significant feature in American homes, a growing middle class with money to spend made pianos a mainstay of 19th-century culture. The demand for ivory then accelerated because it was regarded as the best covering for piano keys, and an adult African elephant tusk of 75 pounds, properly milled, could yield the wafer-thin ivory veneers to cover the keys of 45 pianos.

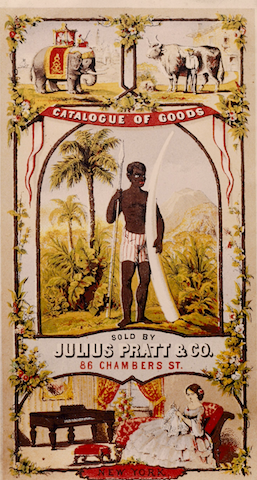

Elephant tusks and Zanzibar natives ca. 1890-1910 – Ivoryton Library Association and the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries

George Read and the Pratt Brothers in Deep River, along with Samuel Merritt Comstock in West Centerbrook (later Ivoryton), had become the leading manufacturers of ivory combs and when the demand for ivory piano keys exploded in the decades prior to the Civil War, these men moved into that field. Their firms, however, were generally underfinanced, which limited production.

Yet, what occurred in 1862 and 1863 made Deep River and Ivoryton the center of ivory milling in the United States. George Read & Company combined with the Pratt Brothers and Julius Pratt & Company of Meriden, Connecticut (Julius was the youngest son of Phineas), to form Pratt, Read & Company in Deep River. The S. M. Comstock & Company in Ivoryton expanded into Comstock, Cheney & Company with the infusion of $4,500 by George A. Cheney, an ivory trader who spent 10 years as a buyer on the East African island of Zanzibar.

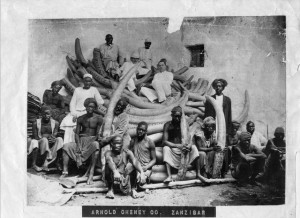

Comstock, Cheney employee cutting elephant tusk ca. 1900 – Ivoryton Library Association and the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries

Connecticut’s Ivory Giants

These mergers proved monumental for the piano industry; each factory expanded into the manufacture not only of ivory key veneers but of piano actions, keyboards, and sounding boards as well. Employment rose rapidly, so that by 1900 these two factories employed more than 1,400 men and women.

A few smaller ivory shops, such as A. Griswold & Company and George Dickinson & Company, also established roots in the immediate area, but they did not approach the size of the two giants, and in Ivoryton, Comstock, Cheney & Company absorbed most of these small firms. The increased employment opportunities in the late 19th century drew hundreds of immigrants to the area’s ivory workshops; the majority of these workers came from Poland and Italy.

During the initial decade of the 20th century, the annual figure for number of pianos sold exceeded 350,000. Pratt, Read & Company, along with Comstock, Cheney & Company, supplied the majority of keyboards and actions to the various piano manufacturers, including Baldwin, Chickering, Wurlitzer, Everett, and Sohmer.

Factories also produced toiletries, toothpicks, billiard balls, letter openers, and many other household items made from ivory. These items emerged from the thousands of tons of ivory purchased and shipped from Africa. Comstock, Cheney & Company records show that the firm milled an estimated 100,000 tusks before 1929. The ivory initially came from central East Africa through the island port of Zanzibar, but later purchases came from the Congo and Egypt as well.

The Decline of the Ivory Empire

The peak year for piano production in the United States was in 1910. After that, the radio and gramophone moved people away from the piano, and the movies and the automobile took them out of their homes. During the Great Depression consumer demand for pianos plummeted and both companies saw a steep decline in sales. For example, Pratt, Read & Company saw its business income fall by 90 percent between 1922 and 1932.

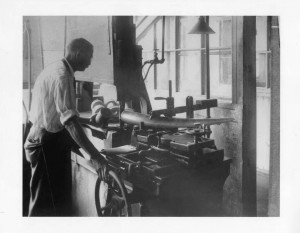

Comstock, Cheney & Company ivory shop on West Main Street in Ivoryton, 1920s – Malcarne Collection, Ivoryton Library Association and the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries

Whereas Pratt, Read & Company bolstered the economy largely in Deep River, Comstock, Cheney & Company provided its benefits to Ivoryton. The latter company actually adopted a more paternalistic style of management and promoted the idea of welfare capitalism, wherein factory-sponsored activities were carried on in the community to benefit the quantity and quality of factory production. What resulted in Ivoryton was a complete “company town,” with Comstock, Cheney & Company owning (or financing) many homes, stores, boarding houses, and a fine meeting hall.

After lengthy discussions, and to reposition themselves for a smaller market, the two companies merged in late 1936 under the name of Pratt, Read & Company, and centered production in Ivoryton where the facilities proved more up to date. World War II then virtually curtailed piano and ivory production when the government called for labor to be redirected toward military needs and Pratt, Read & Company’s workers manufactured gliders for the war effort.

After the war, normal production resumed and for a period, a pent-up demand for pianos kept Pratt, Read & Company busy. Ivory became expensive, however, as the size of the available tusks declined due to over-hunting of large bull elephants. As a result, 1954 saw the last shipment of ivory to Ivoryton. After that, plastic keys became the norm, and further economic pressure required Pratt, Read & Company to build a new plant in the town of Central, South Carolina, and move about 50 percent of its production there.

Pratt, Read & Company, so long associated with the lower Connecticut River Valley, closed as a piano parts manufacturer in the late 1980s. Harwood Comstock, a great-great-grandson of Samuel Merritt Comstock, carried on the corporate name as president of the Pratt-Read Corporation. The company, now called Pratt-Read Tools and based in Illinois, manufactures screwdrivers, the same product that was Samuel’s first business venture in 1834.

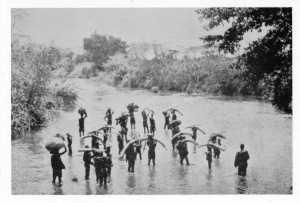

An ivory hunter’s caravan fords a stream near the border of the Belgian Congo, ca. 1908 – E.D. Moore Collection, Ivoryton Library Association and the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries

Consequences of the Trade

An important piece of the ivory story concerns the ways that those involved in its trade obtained and transported this valuable material. The exploitation of the African Bush elephant, Loxodonta Africana, is an obvious part of the story. Less well known is that slave labor moved the tusks the long distances from the African interior to the coast on the Indian Ocean. Established slave trade routes already existed through central East Africa, so when the demand for ivory burgeoned in the 1840s, the ivory trade took advantage of these ready-made routes and thousands of tribal people found themselves forced into slavery to carry the tusks.

Depending on where hunters and buyers obtained the tusks, they might need to be carried for hundreds of miles to a port. Missionaries from Europe, in Africa to spread Christianity, left vivid accounts of the suffering of ivory’s human porters. Though precise figures are not available, David Livingstone, the famous Scottish physician and clergyman who spent decades in Africa, violently opposed the use of enslaved workers and is said to have estimated that five Africans died for every tusk moved to the coast for export. The American Civil War created some pressure to end slavery in Africa, but it continued there through 1897.

Donald L. Malcarne was a historian of the lower Connecticut River Valley and a past president of the Essex Historical Society. Brenda Milkofsky curated the exhibition, From Combs to Keyboards: The Ivory Cutting Industry in the Connecticut Valley, while Director-Curator of the Connecticut River Museum in Essex, CT.