By Patrick Skahill

To be properly cultivated, silk depends on one thing: the silkworm. And silkworms depend on one food source: mulberry trees. Since the 1770s, New England farmers had tried to grow the notoriously delicate plants, but low temperatures and unpredictable weather made sustained cultivation virtually impossible. This changed in 1826, however, when planters introduced a hardier variety of mulberry tree, morus multicaulis, to the United States.

US Silk Market Booms and Crashes

In 1833, three sons of Manchester’s George Wells and Electa Woodbridge Cheney—Ward, Frank, and Rush—invested heavily in the new plant. By cultivating the hardier mulberry tree domestically, they hoped to undercut overseas markets and eliminate manufacturing costs associated with silk importation.

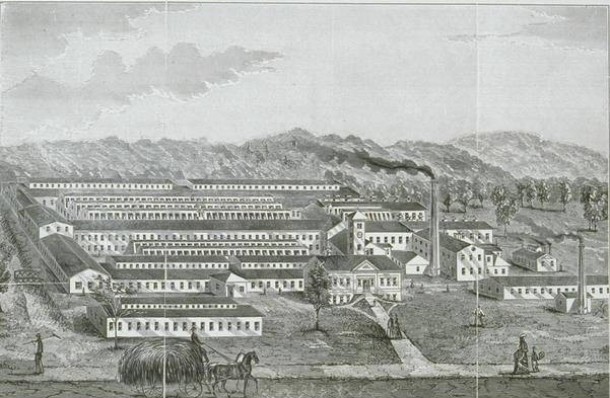

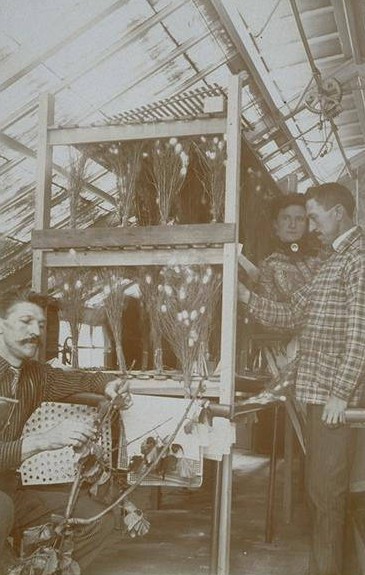

Cocoonery, Cheney Brothers, Manchester, ca. 1900 – Connecticut Historical Society

Initially, at least, their investment seemed like a good bet. Investors embraced the idea of locally-grown silk and mulberry tree prices rose from $4 per 100 in 1834 to $30 per 100 in 1836. The Cheneys expanded their Manchester farm and opened satellite facilities in New Jersey and Ohio.

But morus multicaulis wasn’t as hardy as everyone had hoped. Recurrent blights wreaked havoc on farms across the northeast and the growing specter of a widespread crop failure made investors wary. Following the Panic of 1837, investors simply stopped giving money to the silk “experiment.” Mulberry farms disappeared and by 1840 the silk speculation bubble had entirely burst. Mulberry trees were sold as pea brush (branches and twigs, usually prunings, used as supports for pea plants) to or simply burned by farmers unable to push the worthless crop.

The Cheneys, however, acted before the silk crash took full effect. They had the foresight to determine that the future of the American silk market lay not in the production of the raw material but in its processing. Ward, Frank, and Rush partnered with brother Ralph and colleague Edwin Arnold in 1838 to open the Mt. Nebo Silk Mills in Manchester. Mt. Nebo began modestly, maintaining only $50,000 in capital and working out of a 2-story, 32-by-45-foot plant, which gathered all its power from the adjacent Hop Brook River.

John and Seth Cheney, both successful portrait artists, often loaned funds to sustain the operation and, by 1843, only 18 employees worked at the plant—all putting in 72-hour work weeks. The company was growing, and in 1847 the Cheneys stumbled onto their first big break: the Rixford Roller.

Rixford Roller is First of Cheney Innovations

Patented by Frank Cheney, the Rixford Roller revolutionized silk manufacturing by replacing the direct drives found in older-style silk rollers with a new friction-powered drive that wound raw silk into hardier, double-twisted threads. The hardier strings meant less breakage and production at Mt. Nebo skyrocketed.

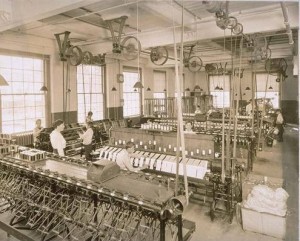

Mill interior, Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company, ca. 1918 – Connecticut Historical Society

In 1854 Mt. Nebo became the Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company, and the firm opened a second factory, where silk ribbon was produced, on Morgan Street in Hartford.

The following year, Cheney Brothers began spinning waste silk—taken from damaged cocoons—and became the first factory in the world to successfully develop a sustainable method for turning waste silk into a final product with no noticeable imperfections. The company invested heavily in the waste spinning technology. It plowed approximately $30,000 into factory refits to facilitate the new production.

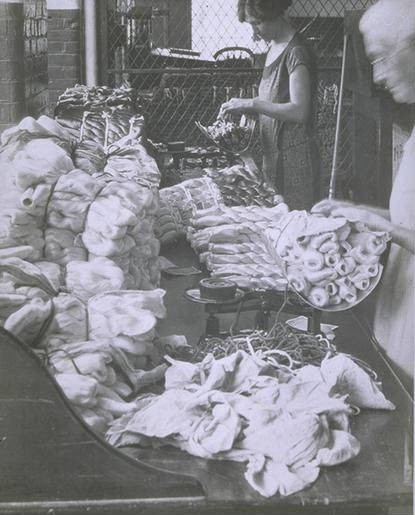

Women weighing raw silk, ca. 1920 – Connecticut Historical Society

This commitment to technology paid off: Cheney’s capital stock increased to $400,000 and, by 1860, the mill employed 600 workers and boasted an annual production valued at about $551,000. Cheney’s two innovations established the company’s reputation for ingenuity and Cheney began to attract many highly trained machinists.

One of these, Christopher Spencer, an ex-Colt firearms employee, expanded the company into the arms industry with his revolutionary Spencer Gun, patented in 1860. Developed in Cheney’s Manchester factory, this rifle boasted a revolutionary firing rate of 15 to 16 shots per minute.

In 1863, Spencer brought his gun to Washington, DC and arranged a personal demonstration for President Abraham Lincoln. On August 13, the president fired seven shots from the Manchester-made gun and was impressed by the rifle’s accuracy and speed. He immediately ordered all the weapons the company could make.

The Cheney Brothers helped Spencer organize a company to manufacture the carbine and leased factory space in Massachusetts. More than 200,000 Spencer Guns were ultimately produced before the Spencer arms division was sold to the Winchester company following the Civil War.

Cheney’s Business Flourishes and Fuels Community Growth

In 1867, the company opened Cheney Hall, which served as the cultural center of Cheney Village well into the following century. Throughout the years the hall hosted dances, concerts, plays, town gatherings, worship ceremonies, and graduations. Notable speakers at the Hall included abolitionist Wendell Phillips, Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, and women’s rights leader Susan B. Anthony. Cheney Hall even served as Manchester’s hospital during the 1918 flu epidemic.

In 1869, the company constructed the South Manchester Railroad, which, at the time, was the only family-owned railroad in the United States. Nicknamed “Cheney’s Goat,” the roughly 2-mile rail functioned primarily as a transport for silk between Cheney’s Manchester and Hartford mills, but the line also took passengers. Many Cheney workers did not need to commute to their job; they lived on plant property in company-built homes. Strikingly modern for their time, Cheney houses boasted some of the first indoor plumbing in Manchester and all were powered by the company’s own gas and electric firm.

In 1873, the company shortened its name to Cheney Brothers. Nine years later, factory worker J.M. Grant introduced another key Cheney innovation, the Grant Reel. This machine changed how raw silk was wound, avoiding parallel yarns in favor of a regular crisscross pattern, which cut down on snarls. Grant Reels were soon found in factories all over the world, from France to the Asia.

Great Depression Reverses Cheney Brothers’ Fortunes

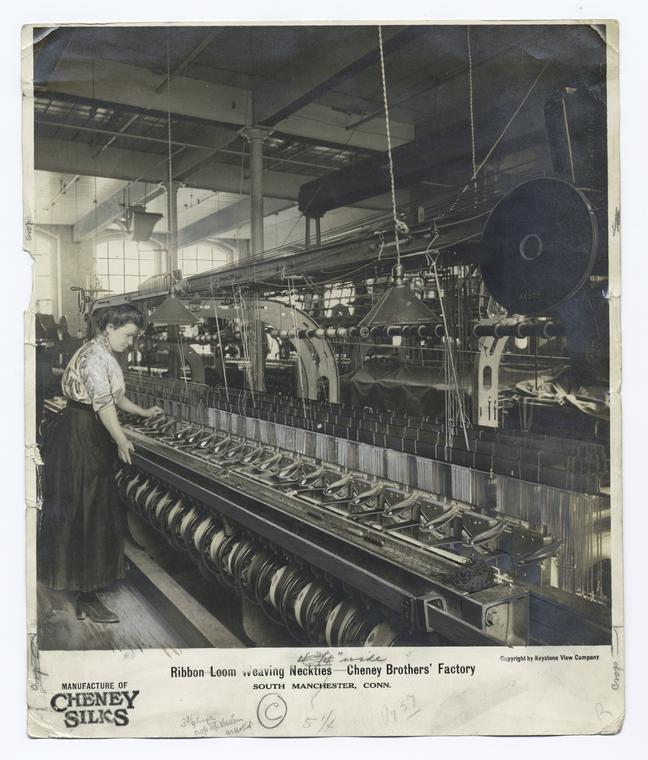

Cheney Brothers ribbon loom weaving neckties – New York Public Library Digital Gallery

In the early 20th century, demand for silk continued to grow. By 1913, American manufacturers consumed as much raw silk as France, Germany, Italy, and England combined. America was at the forefront of international silk manufacturing, and the Cheney Brothers dominated the American market.

The 1920s proved to be a golden age for the company. Cheney Brothers was the only factory in the world carrying silk all the way from its raw form to a finished product, and employment rolls peaked at well over 4,500 workers—a figure that represented more than 25% of the population of Manchester. Factory property encompassed more than 175 acres and in 1923, Cheney recorded a record profit of $23 million.

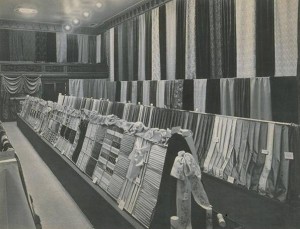

Display of Cheney Brothers silk ribbons and fabrics, Manchester, 1908 – Connecticut Historical Society

Business was booming but, once again, the silk bubble was about to burst. The Great Depression hammered all sectors of the American economy but decimated luxury manufacturing. Just three months after the 1929 stock crash, the value of Cheney’s on-hand finished goods dropped by $6 million. Two years later, Cheney’s income contracted to $10 million and the company reported a $2.5 million operating loss. Cheney Brothers struggled to maintain solvency and turned to selling off assets in Cheney Village.

From 1929 to 1933 the company sold their high school building, gas and electric firms, several schools and recreation buildings, the South Manchester Water Company, the South Manchester Sanitary and Sewer District, and the South Manchester Railroad. Even these measures could not restore company finances, and in 1935 Cheney Brothers applied for reorganization under a new federal bankruptcy law.

The company auctioned off many of its tenant houses, selling back only 61 to the families occupying them. The total received for all property was only about 75% of its assessed value.

WWII Ushers in Synthetic Fabrics and Hastens Silk’s Decline

In 1938 the company partnered with DuPont and the Army Air Force to develop a new parachute, which was produced by Cheney’s newest subsidiary—Pioneer Parachute. Cheney’s production lines shifted nearly exclusively to wartime contracts, and due to Japan’s silk embargo, Cheney Brothers abandoned silk in favor of nylon, rayon, and other synthetics, which were stronger, cheaper, and more readily available.

By the end of the war, Americans had acquired a taste for these more durable synthetics and silk looms around the nation stopped spinning. In 1930 approximately 100,000 silk looms operated in the United States; in 1950 that number had dropped to just 3,000.

In 1955 J.P. Stevens and Co. of New York bought Cheney for $5 million, liquidated large portions of the mill’s property to the town of Manchester and slashed Cheney’s workforce from 2,600 employees to 600. They also refocused the industry’s main products to velvet goods.

The following year, Pioneer Parachutes was sold to Reliance Manufacturing Co. of New York and Stevens sold the Manchester silk mill to LaFrance Industries. Employment dwindled, and in 1978, six years before the mill closed, the 15-block neighborhood of mansions, factory buildings, and worker houses known as “Cheney Village” was reclassified as a national historic district.