By John Wood Sweet

Out of almost 12 million African captives who embarked on the Middle Passage to the Americas, only about a dozen left behind first-hand accounts of their experiences. One of these was Venture Smith, whose A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa: But Resident above Sixty Years in the United States of America. Related by Himself was published in New London, Connecticut in 1798.

Smith’s brief, dramatic account is a powerful reminder of colonial Connecticut’s diversity, shaped by networks of migration and trade that extended not just to England but also to the West Indies and West Africa. His story is a reminder that alongside the war over political principles and national autonomy waged by Revolutionary New Englanders there was another, bitterly fought struggle over slavery, freedom, and equality.

A Child Named Broteer

Around 1730, in a place called Dukandarra in the savannah region of West Africa, a family named its new child Broteer. According to the narrative, his father, a local leader, exercised authority with honor and generosity. His mother was one of several wives. In time, young Broteer worked tending large herds of sheep. Their world was turned upside down when a marauding army threatened, betrayed, and ultimately overwhelmed their people. Broteer looked on as the army tortured and killed his father for refusing to disclose the location of his treasure. Broteer was taken captive and marched to the coastal slave-trading center Anomabo (in present-day Ghana) for sale.

As Broteer later recalled, an officer on a Rhode Island slaver commanded by a “Captain Collingwood” purchased him for “four gallons of rum and piece of calico cloth.” The vessel was probably the Charming Susannah, which departed Newport in late 1738 and returned in September 1739. Renamed Venture by his captors, Broteer survived the smallpox epidemic that ravaged the ship during the Middle Passage, and while most of the surviving captives were sold in Barbados, he was brought to New England.

In Newport, where the slave traders landed Venture, and in the fertile New York and Connecticut farmland along the eastern end of Long Island Sound where he spent the next three decades, as many as one in five people were of African origin.

A Man Called Venture

Smith’s account of slavery emphasized two things: the system’s violence and injustice, and the bargaining power he gained through his extraordinary physical strength and self-discipline. During the 1740s and early 1750s, George Mumford owned Venture. Mumford rented Fisher’s Island from members of the Winthrop family. He operated the 3,000-acre property as a large, commercial farm, raising mostly sheep and dairy cows.

In his mid-20s, Venture married a fellow enslaved person named Meg. And, soon thereafter, he made an unsuccessful runaway attempt. A newspaper advertisement placed by his owner in April 1754 confirms this account and offers the only contemporary physical description of Venture: “he is a very tall Fellow, 6 feet 2 Inches high, thick square Shoulders, Large bon’d, mark’d in the Face, or scar’d with a Knife in his own Country.”

Soon thereafter, Mumford sold Venture to a farmer named Thomas Stanton II in Stonington, Connecticut. Venture convinced his new master to purchase his wife Meg, but Venture’s relationships with the Stantons were marked by betrayal and violence.

At one point around 1760, Venture intervened in a conflict between his wife and Mrs. Stanton. His master retaliated by clubbing him brutally and stealing the money he and Meg had been saving up to purchase their freedom. Venture complained to a local justice of the peace to no avail. Ultimately, Venture was sold to Oliver Smith, a small-scale Stonington merchant, and they reached a deal whereby Venture earned the money to purchase his freedom through various kinds of work, including cutting vast amounts of cordwood. It was in honor of the one master who did not betray or cheat him that Venture adopted the surname “Smith.”

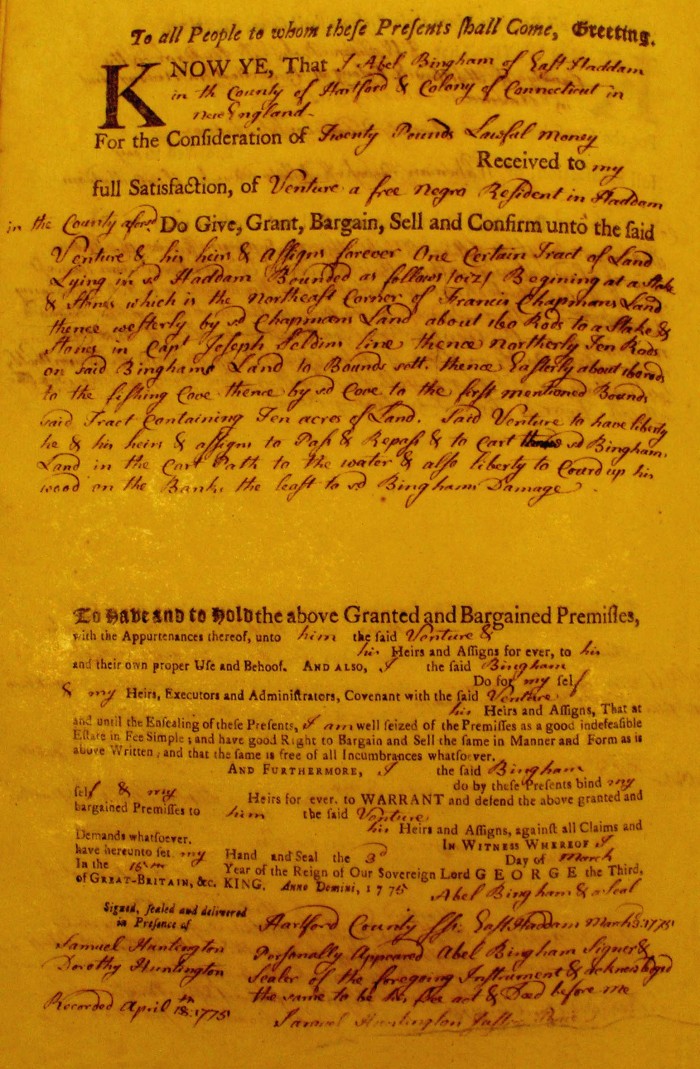

Venture Smith’s first real-estate purchase in East Haddam, 1775 – Digitized by Cameron Blevins from the land records of the town of Haddam

Freedom Brings Success and Struggle

As a newly free man, Venture Smith set out earning money and investing it so that he could reunite with and support his family. Thomas Stanton still owned Meg and their two sons, and a member of Mumford family owned their eldest child, Hannah.

Smith worked as a sailor on a whaling expedition, fished, and cut cordwood in various places around Long Island Sound. He also invested in land. In 1770, he bought a 26-acre parcel that bordered the farm of his former master Thomas Stanton. (That area is now the Barn Island Wildlife Preserve.)

In 1775, he used proceeds from the sale of this land to purchase a small piece of land on Haddam Neck, Connecticut, where he cut lumber. Within a few years, his land in Haddam Neck grew to over 100 acres. There, he reunited his family and pursued a variety of entrepreneurial activities–farming, lumbering, fishing, and working as a small-scale trader along the Connecticut River and the east end of Long Island Sound.

Recent archaeological excavations of his homestead, now owned by the Connecticut Yankee Utility Company, uncovered the remains of a house and barn as well as ancillary storage buildings, a blacksmith shop, and a dry dock for repairing boats. But Smith’s account makes it clear that as proud as he was of his successes, he was also conscious of the obstacles that had been placed in his path. Long after he became free, unscrupulous and sometimes openly racist men continued to cheat him in business transactions. And the courts could not be relied upon to give him equal justice.

The Story He Told

By the time Smith prepared his life story for publication in 1798, he was showing the signs of his old age: his strong, tall body was bowed and he was going blind. Since he was not literate, he must have had help getting his story written down. This may have been Elisha Niles, a local schoolteacher, but no contemporary evidence has surfaced to support this attribution. The narrative was published by a very politically active newspaper publisher. Nonetheless, there is good reason to believe that the Narrative as published in 1798 reflects Smith’s own distinctive voice.

In many cases, specific details he mentions can be corroborated with contemporary evidence. But more importantly, the tone of his narrative and his emphases are distinctive and unusual and therefore unlikely to reflect the influence of others. Smith emphasized continuities between life in West Africa and in North America; he emphasized the violence of slavery in New England, and he described his struggle for freedom and equality as a lop-sided series of struggles rather than as a simple consequence of the spirit of freedom and revolution that swept the new nation.

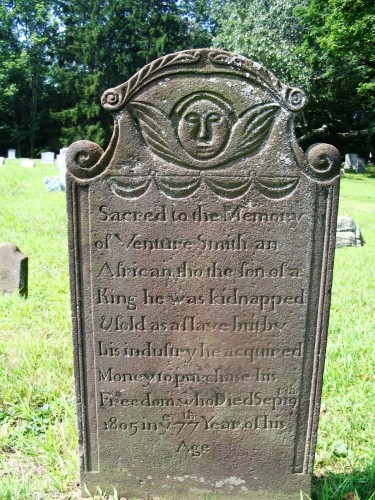

Venture Smith died in 1805. He was buried in the graveyard of the First Congregational Church in East Haddam. Alongside him are buried his wife Meg, who died several years later, and other members of their family. Smith’s gravestone, which can be seen there to this day, was carved by John Isham, a well-known carver in the region. It describes him as “Venture Smith, African. Tho the son of a King he was kidnapped and sold as a slave but by his industry he acquired Money to Purchase his Freedom.” Since then, he has been widely remembered in the region for his industry, integrity, and successes.

John Wood Sweet, PhD, is an associate professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and is currently working on a book entitled The Captive’s Tale: Venture Smith and the Ordeal of the Colonial Atlantic.