By Patrick J. Mahoney

The Blue Laws of the Colony of Connecticut is a term that has been used to collectively refer to the orders of the Connecticut General Court in 1650, and later the Code of Laws of the Colony of New Haven enacted in 1655. While occasional references to the infamous “blue laws” appeared in newspapers and pamphlets in the pre-Revolutionary period, no examples of the laws themselves existed before “a sketch of some of them” materialized in the Reverend Samuel Peters’s 1781 work, A General History of Connecticut, from its First Settlement under George Fenwick, Esq. to its Latest Period of Amity with Great Britain.

The First Connecticut Code

In May of 1650, the General Court of Connecticut adopted what became known as the First Connecticut Code. The code was the result of work undertaken by Roger Ludlow, who, in 1646, set out to amend the preexisting Capital Laws of 1642, which were mostly borrowings from those of neighboring Massachusetts. Not straying far from the existing set of laws, the 1650 revisions pertained mostly to retaining the civil and religious order of the community.

Recognized as the main source for what later became Connecticut’s blue laws, the New Haven Code of Laws came about during various periods of the late 1640s, and then underwent revisions by Governor Theophilus Eaton in 1655. After reviewing a “new book of laws in the Massachusetts Colony” and a “small book of laws newly come from England,” Eaton set about making his changes. The court then considered and voted upon the governor’s modifications, and officials placed an order to have the laws drawn up by a printer in London. The following year, 500 volumes headed to New Haven for distribution.

Although revisions to the laws appeared in 1672, and again in 1702, the printed copies largely fell out of circulation. Despite their rarity, copies preserved by antiquarian societies and private collectors proved useful in combating later exaggerated claims about the content of the blue laws. In one such case in 1838, Connecticut’s secretary of state, the Hon. R. R. Hinman, compiled and reprinted the content of a preserved copy of the original New Haven Code under the title The Blue Laws of New Haven Colony, usually called Blue Laws of Connecticut.

Who the first person was to use the term “blue laws” to describe colonial Connecticut laws, and when that occurred, remains unknown. The two most prominent theories, however, attribute the term to Connecticut Episcopalians and other religious dissenters in the mid-18th century, or possibly those within the neighboring province of New York who voiced their disdain at the rigidity of New England puritanism. James Hammond Trumbull noted that within the rhetoric of the period, the denotation of being blue was one of reproach. He noted, “to be ‘blue’ was to be ‘puritanic,’ precise in the observance of legal and religious obligations, rigid, gloomy, over-strict, -in a word, to be in morals and manners the very opposite of a courtier, wit, or gallant of the time.”

Reverend Samuel Peters and the Transatlantic Blue Law Controversy

Connecticut’s blue laws received international notoriety after their inclusion in Reverend Samuel Peters’s General History of Connecticut. After relocating to London during the turmoil of the Revolutionary War, Peters published a semi-historical account of his former New England home in 1781. The work met with strong reactions from readers on both sides of the Atlantic who remained unsure as to whether the claims made by Peters, specifically his outline of Connecticut’s infamous blue laws, were intended to be read satirically or as a legitimate historical profile.

Historians note that as a loyalist Anglican who had been intimidated and forced to leave his wealthy Connecticut estate at the outset of the American Revolution, the exiled Peters perhaps maintained some personal motivation for embellishing the severity and eccentricity of the blue laws in an effort to reinforce preexisting English claims of religious fanaticism and bigotry within the New England colonies. Other scholars assert that given Peters’s bizarre descriptions of the topography of the colony and a number of near-mythical occurrences presented as historical fact, his account of the blue laws became merely part of a larger attempt to find success in the emerging literary genre of the tall tale.

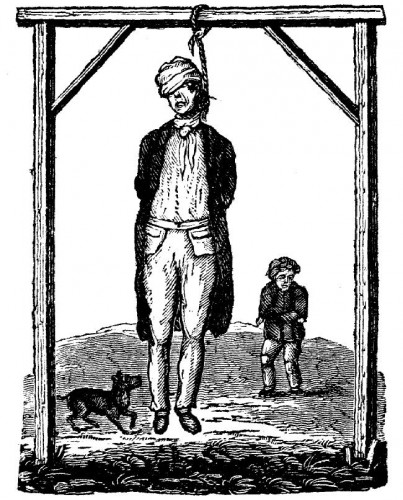

The title page from James Hammond Trumbull’s book The True-Blue Laws of Connecticut and New Haven…

Among Peters’s more peculiar assertions attributed to the blue laws was the claim that stylistically, “every male shall have his hair cut round, according to a cap.” He further asserted, “when caps were not to be found, they substituted the hard shell of a pumpkin, which being put on the head every Saturday, the hair is cut.” Further fantastic claims included dress codes designed to deter lavishness, a strict forbiddance of mothers kissing their children on the Sabbath, and regulations against a number of activities including making beds, shaving, traveling, running, leisurely strolling, or walking in any manner deemed irreverent on the Sabbath day. Peters noted that the punishments for breaking the various laws included fines, banishment, public admonishment, mutilation, and even death.

Regardless of his actual intentions in undertaking a historical profile of his former home, his work proved successful in reinforcing the contemporary English view of Americans as a backwards, fanatical lot. On the contrary, his American readership reacted with outrage, noting that the blue laws as outlined by Peters were a slanderous take on their colonial past. Such was the level of American dismay at Peters’s depiction that the outcry still resonated among the population nearly one hundred years after the work’s original publication (as evidenced by James Hammond Trumbull’s 1876 refutation of its claims).

Modern Blue Laws

In a modern context, blue laws became regarded in a more general sense as “Sunday laws,” or those enacted to restrict or ban certain activities on what may be religiously held as a day of worship or rest. Separate from their mythical puritan precursors, the more contemporary and wide-ranging variations found enforcement to varying degrees across the United States during the 19th century. Against a backdrop of social and ethnic change (largely brought about by periods of increased immigration), religious reformers sought to impose stricter moral and social codes in an effort to regulate the populations’ Sunday activities. As a result, many Americans found themselves fined or arrested for working, consuming alcohol, traveling, or partaking in recreational activities on Sundays. Remnants of the blue laws remain to the present day in select states, most notably in the restriction of certain sales on Sundays.

Patrick J. Mahoney is a Research Fellow in History & Culture at Drew University and former Fulbright scholar at the National University of Ireland Galway