Connecticut’s struggles with the issue of capital punishment date back to its earliest days as a colony. Starting in 1636 and ending in 2005, Connecticut witnessed 158 executions. Throughout this period, changing ideas about crime, punishment, and human rights played out in public debates about the effectiveness and morality of capital punishment.

The Capital Laws of New England went into effect between 1636 and 1647. Criminals convicted of offenses such as sodomy, witchcraft, blasphemy, rape, rebellion, manslaughter, and pre-meditated murder all paid for their crimes with their lives. By the time of the American Revolution, many of these crimes still carried a death sentence, while lesser crimes like burglary meant corporal punishment by branding or whipping for the first two offenses and death for a third. The preferred method of execution during this time was hanging.

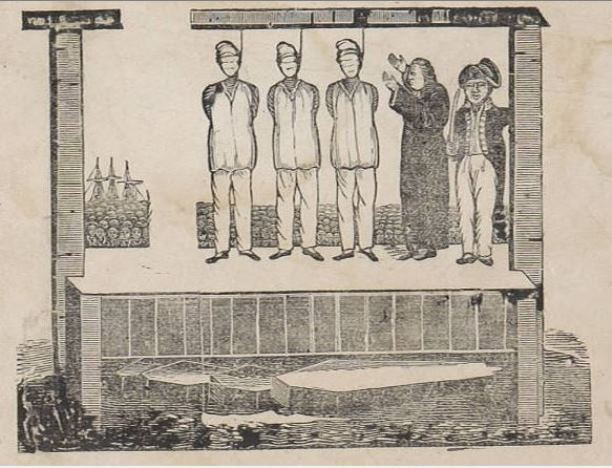

Executions as Public Spectacle and Warning

Public hangings were a part of Connecticut culture in the late 1700s. Sometimes tens of thousands of spectators showed up to watch the condemned die. Local merchants took advantage of the large crowds by selling souvenirs and alcohol to eager spectators. The executions often turned into raucous affairs with onlookers screaming and throwing things at the condemned before turning on each other in drunken brawls. All manner of citizen, including women and children, attended the state’s public executions.

By the middle of the 1800s, however, a great reform movement altered public views on the appropriateness of public executions and the use of capital punishment. As industrialization and urbanization began taking hold in Connecticut, crimes became less about sin and religion and more about addressing social problems. Enlightenment views that called for the more humane treatment of criminals made it increasingly difficult for prosecutors to get convictions for offenses that carried a sentence of death. As a result, states began shying away from the death penalty and started constructing more prisons.

Bird’s-eye view of Wethersfield Prison, Wethersfield, ca. 1880 – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

In 1846, Michigan became the first state to abolish the death penalty (except in cases of treason). In 1852, Rhode Island followed suit, while Massachusetts limited its death penalty offenses to first-degree murder. Proponents of abolishing the death penalty lost momentum for their cause for much of the remainder of the century, however, as the nation focused on the issue of slavery and the Reconstruction process.

Renewed Debate Over Death Penalty

In 1897, with the death penalty debate resurrected, the Hartford Courant reported that a bill before the Connecticut legislature that substituted “life in prison” for “death” in convictions for first-degree murder was rejected without debate. Despite this defeat, the state’s death-penalty abolitionists continued to make a strong case for their cause right up until America’s entry into World War I, when once again the issue took a backseat to matters of national security. The debate did not regain its momentum until the decade of prosperity that followed World War II.

In 1955, Connecticut Governor Abraham Ribicoff submitted a bill to the state legislature that once again called for abolishing the death penalty. This bill met defeat by a margin of over 4 to 1. By this time, Connecticut, which switched its primary method of execution from hanging to the electric chair in 1937, was one of the last states in the Northeast still utilizing the death penalty.

Execution room, Connecticut State Prison, Wethersfield – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Online

In 1958, the US witnessed only 48 executions, the smallest number in almost 20 years. That same year, the state of Delaware voted to end its practice of executing prisoners. The tides were still slowly turning in Connecticut, however, with state representatives voting in favor of the death penalty by a narrowing margin of 166-104 in 1959.

During the Civil Rights era, Connecticut prison reform efforts reached a fever pitch. In 1959, (a year that witnessed Connecticut’s last electric chair execution), the Connecticut Valley Presbytery of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States endorsed a resolution passed by the First Presbyterian Church in Stamford calling the practice of capital punishment “contrary to the core of Christian ethics.” The following year, Hartford hosted a national conference on the issue of capital punishment to foster dialogue on reform.

After a brief halt to executions in the 1970s (due to rulings of the Supreme Court), Connecticut resumed its policy of sentencing prisoners to death, though it had been decades since the last execution in the state. In fact, when Connecticut executed Michael Ross in 2005, it had been over 50 years since the last execution. In 2012, in a move that made national headlines, Governor Dannel Malloy signed a bill making Connecticut the 17th state to abolish the death penalty (and the 5th state to do so in a 5-year period). Today, life in prison without the chance for parole is the toughest penalty handed out to convicts in the state of Connecticut.