By Linda Pagliuco for Connecticut Explored

When British General Charles Cornwallis surrendered his army at Yorktown in 1781, his troops were surrounded by officers and soldiers, muskets, sabers, and artillery secured by the diligent efforts of Connecticut’s own Silas Deane. Deane’s extraordinary role in making the War for Independence viable should have placed him among the illustrious pantheon of America’s “Founding Fathers.”

The son of a blacksmith, Silas Deane rose to become one of the wealthiest merchant traders in Connecticut. His house, now part of the Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum, still stands in Wethersfield, offering visitors the opportunity to learn about Deane and life in Connecticut during the Revolution.

Deane as Connecticut Colony Diplomat

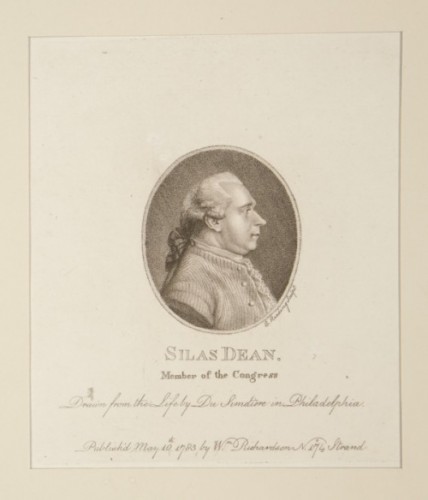

Pierre Eugene Du Simetière, Silas Deane. Member of Congress, 1783, engraving – Yale University Art Gallery

As the winds of war began to blow, Deane, then in his mid-thirties, entered the political arena as one of Connecticut Colony’s delegates to the First Continental Congress (1774) in Philadelphia, where he worked side by side with John Adams, George Washington, and other luminaries. Perhaps most important was the friendship he forged with the illustrious Benjamin Franklin. When Franklin nominated Deane to serve abroad as America’s first diplomat, Deane, who did not speak French and was unaccustomed to travel, accepted with alacrity.

Regrettably, the event that marked the pinnacle of Deane’s career would also mark the beginning of a precipitous downfall. As a secret emissary, he was entrusted with three interrelated duties in Paris: to secure merchandise for commercial trade; to obtain and arrange shipment of arms, clothing, and other supplies for an army of 25,000 troops; and to convince the French government to form an alliance with the colonists against Britain. Deane arrived in Paris on July 6, 1776, unaware that Congress had just declared independence and the war had begun. Franklin had mistakenly thought that Deane could easily operate under cover as a Connecticut merchant purchasing French goods for import. But Deane quickly discovered that his 200,000-Continental-dollar advance had already lost 90% of its value. For the next 18 months, he was forced repeatedly to draw upon his own personal funds to carry out his mission, a circumstance that would soon leave him vulnerable to suspicion and criticism from his own countrymen.

Deane in France

Franklin had arranged for American entrepreneur Dr. Edward Bancroft, who resided in London and had been fully briefed, to act as translator and introduce Deane to influential French supporters. Within days, they paid a call at Versailles to foreign minister Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes, who put them in touch with import-export merchant Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais. Beaumarchais was very interested in offering military commodities on credit, and assisted Deane in arranging for eight shiploads, containing military accoutrements of every sort, to be sent to the Continental Army. Deane also recruited the Marquis de Lafayette, Baron von Steuben, and others to help Washington create a professional fighting force. Deane made certain that, should his account books ever land in British hands, nobody could decipher his transactions. Deane’s bookkeeping practices would soon be used against him with devastating effect.

Franklin and Virginia politician Arthur Lee joined Deane in December 1776, forming a new, official commission to secure a formal, public alliance with France. Deane and Franklin, already fast friends, worked closely together, leaving Lee, who already disliked both of his colleagues, bitterly resentful. Lee covertly began undermining their efforts, writing letters to allies in Congress maligning and mischaracterizing their work. Although Deane and Franklin were aware of his duplicity, they believed they had nothing to fear. What they didn’t know, however, was that Bancroft, now employed as their secretary, was a double agent.

A Disgraced Deane Answers to Congress

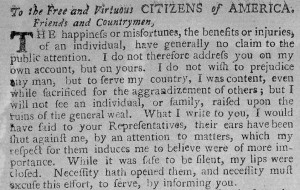

To the free and virtuous citizens of America a broadside addressing the public regarding his actions by Silas Deane, Philadelphia, 1779 – Library of Congress, American Memory

Two years later, on February 6, 1778, the American diplomats were elated to accomplish their goal, with the signing of the Treaties of Commerce and Alliance. But Deane’s celebratory mood soon was dashed when Congress recalled him to Philadelphia. Lee had asserted to Congress that Deane had misused his position to make a private fortune through privateering and insurance fraud. Deane went home to hotly deny the charges, and although Congress gave him a hearing, no final determination was made. Deane became widely known as a traitor and embezzler.

Dejected and determined to clear his name, Deane returned to Europe, but the French, unwilling to expose the details of their diplomatic choices, had seized his records and refused to release them. Further controversy erupted in late September 1781 when some of Deane’s personal letters expressing doubts about the benefits of independence were made public through Bancroft’s machinations. By then, Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown, and the public viewed Deane’s remarks as treasonous. Having spent his considerable personal fortune on war supplies, Deane was now impoverished and unwelcome in his own country.

A Mysterious Death and Exoneration

Bancroft had returned to London, and in 1783 he encouraged Deane to settle there as well, for reasons of his own. Bancroft provided him with companionship and financial assistance and served as his physician. When Deane’s brother wrote that it was safe to come home, Deane booked passage, resolving to rehabilitate his reputation at last and begin anew. In September 1789, he boarded ship, in good spirits and seemingly good health. Among his luggage was a supply of medicines provided by Bancroft. He ate a hearty breakfast, then took ill while walking the deck with the captain, collapsing into a coma. Deane was dead within four hours.

The cause of death was never determined. At the time, the most popular theory was suicide, perhaps by overdose of laudanum, though witnesses described him as cheerfully anticipating his homecoming. Another theory is that Bancroft, an authority on poisons, had “doctored” the medicines in Deane’s possession. Bancroft may have feared exposure as a double agent.

The slanderous accusations of Deane made by Lee have never been proved or disproved. In 1841, though, in response to a petition from his granddaughter, Congress exonerated Deane. What is certain is that Deane’s trip to Paris was a crucial turning point for America’s Continental Army. For Deane himself, however, it proved tragic, and today, sadly, to most Americans, his name remains obscure.

Linda Pagliuco is a historian at the Webb-Deane-Stevens and Nathan Hale Homestead museums.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal) Vol. 10/ No. 1, WINTER 2011/2012.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.