Nicknamed the “Keystone Division,” the United States Army’s 28th Infantry Division came together in 1917 by combining units of the Pennsylvania National Guard. By the end of World War II, however, there were over 200 soldiers from Connecticut serving in the 28th Division. The 28th saw action in some of the most intense fighting of the Second World War and earned the nickname the “Bloody Bucket” division.

Training for the 28th Division took the men all over the country—and then the world. From August of 1941 until March of 1942, the division trained in Indian Gap, Pennsylvania, then at the A.P. Hill Military Reservation in Virginia, and, finally, at Camp Livingston in Louisiana. In 1943, they received amphibious training in Carrabelle, Florida, and practiced fighting on mountainous terrain in West Virginia. They left the United States for Europe on October 8, 1943. Once overseas, they received nine more months of training in Wales and England.

The 28th Infantry Division Enters the War

On July 22, 1944, the 28th Division entered the war with a landing on the beaches at Normandy. All about them, the men witnessed the aftermath of the D-Day landings. The area around Normandy remained covered in refuse from the Allied invasion, and the division’s soldiers passed through fields lined with white crosses honoring those already lost.

The 28th began fighting in northern France, but the men found themselves unprepared for combat among the thick hedgerows that dominated the area. This resulted in heavy early casualties. Walter Burke of Terryville saw his first action in Fôret de St. Sever, a wooded area in Normandy where his H Company lost 30 men, including their company commander. The fighting was so bitter that the 28th Division suffered 700 casualties on one day alone.

In August the 28th moved on Paris, from which the Germans readily retreated. By August 19th, 833 German prisoners were in the hands of the 28th. It was because of this success that the Germans bestowed upon them their “Bloody Bucket” moniker.

The 28th then crossed the Meuse River into Belgium and Luxembourg. There, in mid-September, they began hammering at the Siegfried Line, a miles-long system of bunkers, barricades, and defensive weapons designed to protect the German border. In November, the 28th was temporarily called away to attack Germans in the Hürtgen Forest. With the Germans entrenched in the forest, free from having to fight on open ground and protected from US air attacks, the fighting took on a renewed intensity. Harry Foss of Bristol, who fought in C Company, remembered losing 100 replacements a day to small arms, mortar, and artillery fire. What US forces did not know was that part of the German resistance stemmed from a desire to use the Hürtgen Forest to protect their northern flank for an upcoming offensive of massive proportions.

The Battle of the Bulge

After having pulled out of the Hürtgen Forest at the end of November, the 28th Infantry Division found itself stretched along a 25-mile front from Luxembourg to the area around Wallenstein. It was then that the Germans launched their massive offensive, later known as the Battle of the Bulge. German Field Marshall Karl Rudolf Gerd von Runstedt initially sent five divisions across the Our River in the direction of the 28th Division. The 28th eventually faced nine divisions in all, holding their ground wherever possible against the onslaught of German military forces.

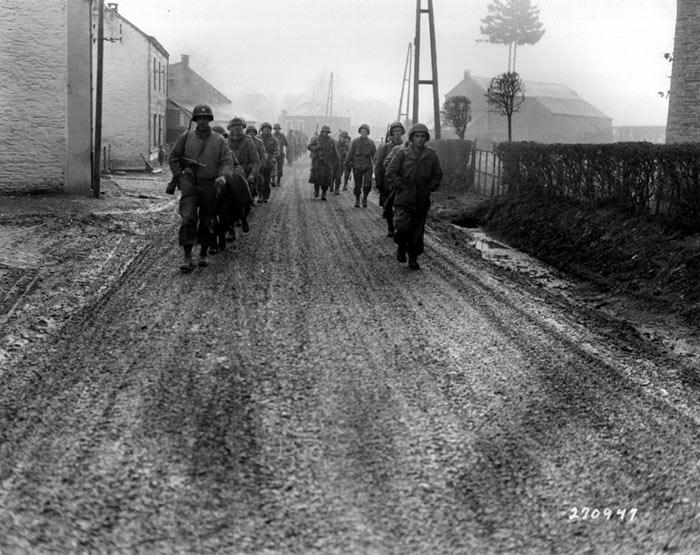

US troops of the 28th Infantry Division, Bastogne, Belgium – US Army Center of Military History

Von Runstedt’s offensive caught the Americans by surprise and he rapidly overran numerous positions held by the 28th. Robert Foraker of Hartford quickly found himself trapped behind enemy lines in Luxembourg. He and approximately 60 others held the town of Munshausen until their ammunition ran out. At 4:30 one morning, the group slipped past their enemy by crawling through and around a number of German half-track vehicles. They then spent the next week hiding by day and traveling by night, only stopping to eat the grass and roots they found along their journey, until they successfully navigated their way back to the American lines.

After the Allies halted the German advance and began pushing them back into Germany, the 28th Division moved on the French town of Colmar, near the German border. Robert Giesel of Windsor and his fellow soldiers marched 60 miles through knee-deep mud in less than four days to capture Colmar in early 1945. When the Germans surrendered soon after, the 28th was in Kaiserslautern, fighting the enemy on their own soil.

The 28th Heads Home

With the fighting in Europe over, the main body of the 28th Division sailed out of Le Havre, France, in July of 1945—headed for US shores. The ships carrying the Connecticut soldiers of the New England group of the 28th docked in Boston in early August. From there, the men went to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, with most on their way home within 24 hours. The Japanese surrendered before the 28th faced redeployment to the Pacific.