In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Thomas Joseph Dodd, a Norwich-born lawyer from Connecticut, served on the United States’ prosecutorial team as Executive Trial Counsel at the International Military Tribunal (IMT). The tribunal, which the Allied nations assembled in order to try Nazi leaders for war crimes, took place in 1945-46. The IMT, which is often referred to as the Nuremberg trial after the German city in which it and subsequent proceedings took place, was an unprecedented effort to hold leaders of a nation state accountable for their wartime actions while also endeavoring to uphold their rights to a fair trial.

Dodd, as the second-ranking lawyer for the US prosecution, supervised the team’s day-to-day management. He, along with chief US prosecutor Robert H. Jackson, also shaped many of the strategies and policies. Additionally, Dodd prepared indictments, presented evidence, and cross-examined defendants.

Kristallnacht and Other Atrocities Documented

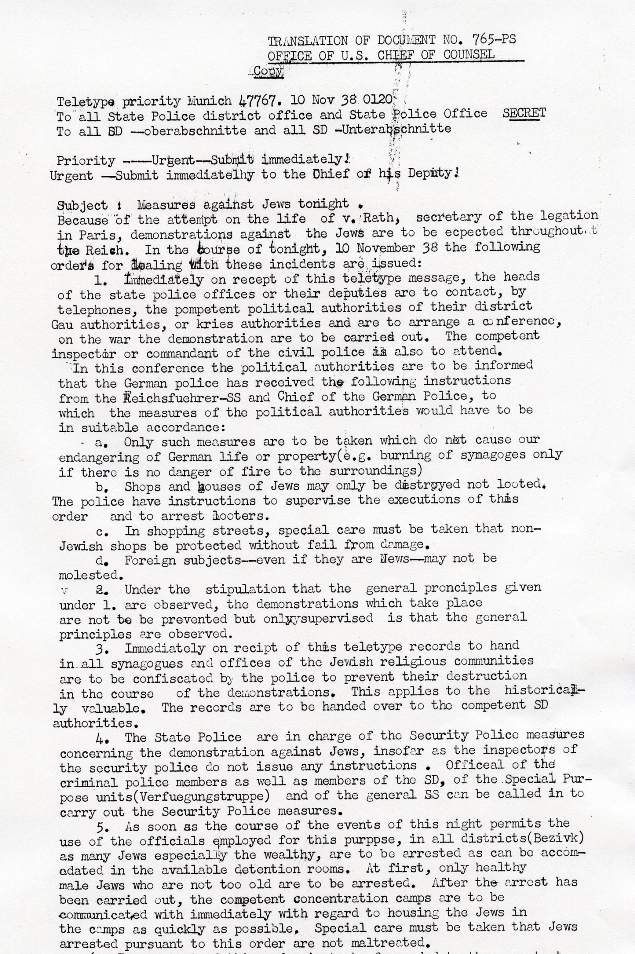

Translation of document no. 765-PS, November 10, 1938 – Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries

Since Dodd’s work at Nuremberg involved accumulating evidence of Nazi war crimes, he and the prosecutorial team reviewed thousands of documents, translated from their original German, which detailed atrocities against the Jewish people of Europe. Among the infamous actions documented was Kristallnacht (Crystal Night).

Also called the Night of Broken Glass, Kristallnacht refers to the riots and pogroms against Jews that occurred throughout Germany on November 9 and 10, 1938. Perpetrators took Jewish lives and destroyed thousands of Jewish businesses, synagogues, and homes. The assassination of a German diplomat in France by a German-born Polish Jew provided the pretext for the rioting. The German state retaliated by barring children from school and suspending Jewish cultural activities and the publication of Jewish newspapers and magazines.

The riots were supposedly initiated and conducted by civilians, but the German police and military allowed the destruction. This complicity is evident in material accumulated for the Nuremberg trial. For example, one document, a translation of a teletype sent to police stations and military units throughout Germany, shows that central authorities instructed local enforcement to allow the burning of synagogues and the destruction of property so long as it posed no danger to non-Jewish establishments. Civilians were not allowed to loot any of the property they destroyed, and it is thought that one reason the Nazis allowed the destruction was to confiscate the Jews’ property for the government. Further, the instructions noted that “as many Jews especially the wealthy, are to be arrested as can be accommodated… .”

Kristallnacht is considered a turning point in the Nazi regime’s persecution of Jews in Germany as well as a culmination of years of tightening control over where Jewish individuals could live or go to school, what work they could do, and what types of civic positions they could hold. The November pogrom is also is considered the commencement of the Nazi’s use of the “Final Solution,” the systematic genocide of an estimated 6 million Jews and other “undesirables” throughout Europe.

Dodd’s Legacy

Dodd, who returned to the United States in 1946 and practiced law in Hartford, later served Connecticut in the US House of Representative and the US Senate. His political career met with acclaim as well as criticism, but his legacy in the field of international justice endures. During the Nuremberg trial, Dodd stated, “Mankind will know that no crime will go unpunished because it was committed in the name of a political party or of a state, and that no crime will be passed by because it is too big, that no criminal will avoid punishment because they are too many.” Today, thousands of translated documents related to the Nuremberg trial and Dodd’s efforts to secure justice for the victims of Nazi crimes are preserved among his papers at the University of Connecticut. Additionally, his work is remembered every other year when the Thomas J. Dodd Prize in International Justice and Human Rights is awarded to an individual or group.

Contributed by Laura Smith, Curator for Business, Railroad, and Labor Collections, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries.