By Susan Aller

In 1904 Caroline Hewins implemented an innovation that would transform public libraries across the United States. She established one of the first rooms in a public library dedicated entirely to children and their books. This room, at the Hartford Public Library, became a model for similar efforts at the New York Public Library and others institutions across the country. Hewins’s programs for children, along with her scholarly articles and lists of recommended children’s books, influenced generations of children’s librarians as well as publishers of children’s books and bookstores.

Childhood Experiences Shaped Career Path

Born in 1846, Caroline Hewins grew up in Roxbury, Massachusetts, where her father, a wealthy Boston merchant, provided a comfortable home for his wife, eight children, and an extended family of aunts, uncles, and grandmothers. Caroline, the eldest child, learned to read by the age of four. Her love for books increased as she read to her younger siblings and as she progressed to reading folk and fairy tales, the English classics, and the stories from Greek, Roman, and European literary traditions. She wrote about her childhood in a 1926 memoir called A Mid-Century Child and her Books. In the last years of her life, Hewins searched for the books that would recreate her childhood library. She far exceeded her goal, amassing a collection of more than 4,000 children’s books that are now preserved as the Hewins Collection at the Connecticut Historical Society and the Hartford Public Library.

Twenty-nine-year-old Hewins moved to Hartford in 1875 to accept a position as librarian of the Young Men’s Institute, a private association dedicated to informal learning, lectures, and debates. Subscribers to the Institute’s library paid to borrow books and use the periodical room. Hewins’s qualifications included an education at Boston’s Girls High School and Normal School, a few years of teaching, and a year of work at the Boston Athenaeum. From this modest beginning, Hewins helped lead the transformation of this small collection into the Hartford Public Library. In addition to becoming its chief librarian, a position she held until her death 50 years later, she rose to national prominence as an authority on library management and as a leading advocate for library work dedicated to the needs and interests of children.

A Pioneer of the Public Library Movement

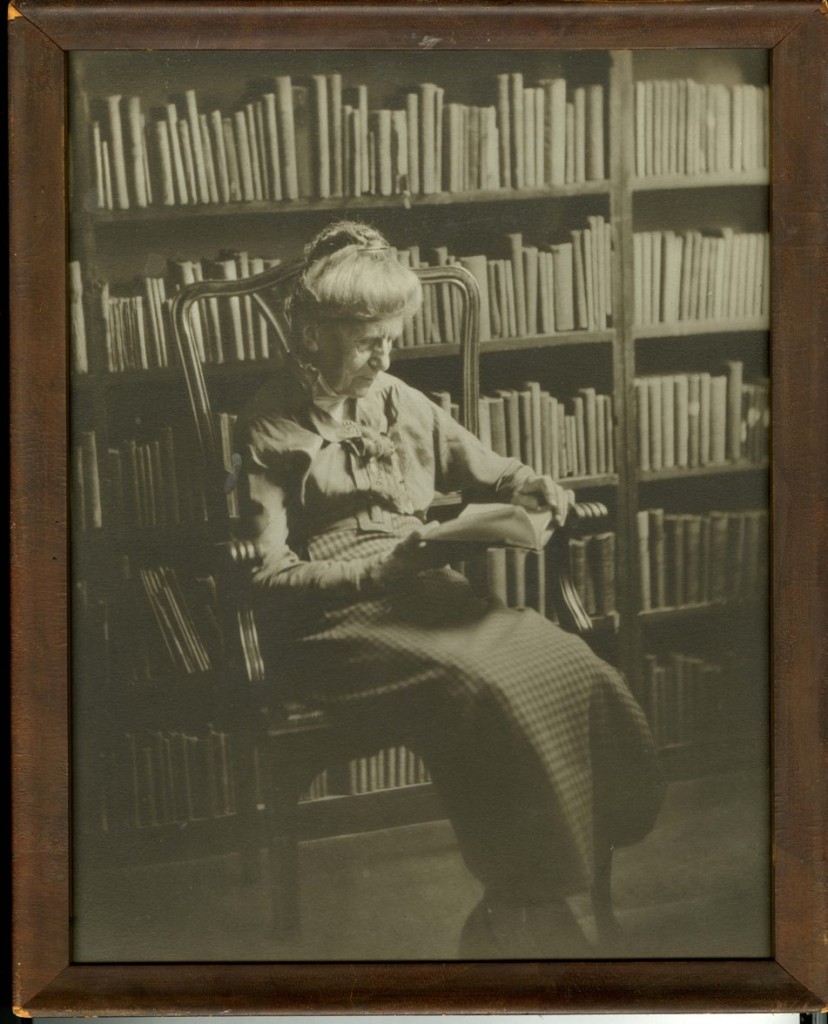

Caroline Hewins, Hartford librarian, 1875-1926 – Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

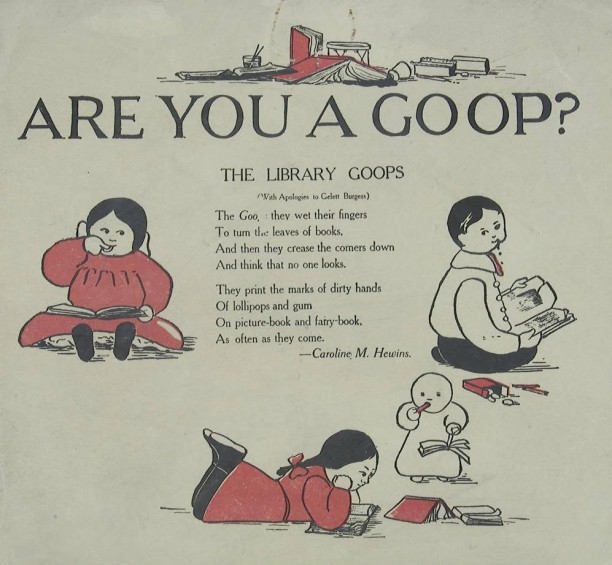

Among the social movements of the late 1800s is the gradual transformation of libraries, which had long been privately funded institutions open to a limited membership, into publicly funded centers dedicated to free education for all. So, unsurprisingly, the Institute Library had not welcomed children prior to Hewins’s arrival. Opinionated, iconoclastic, and not a follower of rules established by others, she believed that children not only deserved access to libraries but that they deserved better books than the formulaic and often violent Horatio Alger stories and weekly novels of the penny press. Accordingly, she focused on providing books by such authors as Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, Hans Christian Anderson, and Charles Dickens to furnish an area for children.

She used the power of the local press and professional library periodicals to encourage parents to bring their children to libraries, to read with them, and to choose quality books that would inspire young imaginations. During the time when an annual subscription to the library cost $3 and allowed borrowers to checkout one book at a time, Hewins worked with Hartford schools to encourage subscription cards at pennies apiece for children.

In 1878 the Hartford Library Association absorbed the Institute—and Hewins continued to innovate. In 1882 she asked a group of leading librarians what they were doing to encourage a love of reading in boys and girls. Based on the discouraging answers, which revealed that little was being done to encourage early readership, she made an impassioned report to the American Library Association (ALA) that galvanized their attention. Within a few years, the ALA had established a Children’s Section so that members could exchange ideas on how to best serve young readers and it was supporting professional training schools for children’s librarians. Hewins broadened her influence through her writing. In 1882 she published “Books for the Young,” the first bibliography of children’s books. Six years later her article in the January 1888 Atlantic Monthly on the history of children’s books elevated the subject to the status of children’s literature, worthy of scholarly attention.

Subsequent funding from donations and taxes enabled the Hartford Library Association to become the free Hartford Public Library in 1892. Its contributors not only included well-to-do benefactors, such as Junius Morgan, but local factory workers and school children as well. By this time, Hewins had already lowered the annual subscription fee to $1 and doubled the membership. In time she established a formal Children’s Room, which, in addition to reading materials, had furniture suitable for youngsters of different ages, pictures of flowers, and abundant light.

Hewins’s work extended well beyond the library’s walls. As founder and executive secretary of the Connecticut Public Library Committee (precursor of the state library commission), Hewins drove her horse and buggy throughout the state to encourage cooperation between schools and libraries for the benefit of children. She arranged for state-wide traveling libraries and book deposit stations at schools, factories, and settlement houses, setting the stage for today’s modern branch library system.

A Mentor to Many

In spite of her growing national reputation, Hewins retained a joyful engagement with her young clients at the Hartford Public Library. She took her small patrons on historical and nature walks, and she wrote plays and pageants for them to enact. When school groups toured the neighboring historical society, which, like the library, was housed in the Wadsworth Atheneum at this time, she invited them into her special library room for lemonade and gingerbread. She even befriended a stray dog that wandered into the library one day and stayed to become its mascot. Only a few years earlier, she had seen signs on libraries that barred dogs and children alike from entering. Hewins’s efforts accorded children—and childhood literacy—greater status within the library and served as a model for other institutions.

Caroline Hewins – Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

During the summer months, Hewins and a favorite nephew often traveled abroad. She sent home letters to the children of Hartford that described her visits to places they had read about in books. These were first published in The Hartford Courant and later collected in a volume called A Traveler’s Letters to Boys and Girls (1923). Additionally, she brought costumed dolls from every country she visited and held a New Year’s Day reception with her collection, hosting little girls and their Christmas dolls. (Today, her doll collection is housed at the Hartford History Center of the Hartford Public Library.)

Hewins had a great capacity for collegiality. Her friends remarked on her energy, cheerful disposition, intelligence, and warm understanding of children. She encouraged others to continue the work she had begun, and a generation of New England women created a synergism that radiated through the library and children’s literature professions. Among the women who called her a friend and mentor were the owner of the first children’s bookstore, the founder of the scholarly journal of children’s literature, The Horn Book Magazine, and many of the first children’s editors at major publishing houses.

In October 1926, Caroline Hewins went to New York City to participate in Halloween festivities at the children’s department of the New York Public Library. The visit was a tradition of long standing between Hewins and Anne Carroll Moore, the New York Public’s children’s librarian. Hewins, who was 80, was in frail health, and on her return to Hartford, she contracted pneumonia. Four days later, on November 4, she died at her home at 190 Sigourney Street. Friends came from all over New England to her funeral at Center Church in Hartford. She was buried in her family’s plot at Dedham, Massachusetts.

In 1911, Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, awarded Caroline Hewins a Master of Arts degree Honoris Causa. She was the first woman to be so honored by the then all-male college. Posthumous honors to Hewins include induction into the American Library Association’s Library Hall of Fame (1951) and the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame (1995). The Caroline M. Hewins Scholarship Fund was established at Hartford Public Library in 1926 for her pioneering work in American librarianship and in special recognition of her work on behalf of children throughout the country. The Caroline M. Hewins Lectureship, an annual presentation at the New England Library Association Meeting, was established by Frederic Melcher in her honor in 1946.

Susan Aller is the author of numerous biographies for children, including ones about Mark Twain, Louisa May Alcott, and Mary Jemison.