By Michael Hoberman

English settlers in New Haven Colony witnessed one of the strangest apparitions in the history of New England, and the retelling of this spectral event has gone down in folk tradition as the Ghost or Phantom Ship of New Haven. Several versions of the story were recorded in print, including one recorded by Reverend Cotton Mather in his 1702 book Magnalia Christi Americana, a history of the religious development of early New England.

In January of 1647, a mere eight years after the city’s founding, a large vessel set sail for England. The voyage had been necessitated by the colony’s long string of failed attempts to engage in remunerative commerce to the West Indies. As Mather put it, “they found their estates sink so fast, that they must quickly do something.”

Colony Pins Its Hopes on New Vessel

A group of the settlement’s most prominent merchants set to work. They arranged for the construction in Rhode Island of what later chroniclers referred to as a “Great Shippe.” This vessel would carry with it across the Atlantic Ocean every kind of marketable merchandise that could be rounded up in Connecticut. The voyage did not meet with an auspicious start. An especially cold winter necessitated the assistance of an advance crew of ice-chopping local residents just to get the ship out of New Haven Harbor and into Long Island Sound. Even then, the ship needed to be towed backward toward the open water.

Indeed, from one version of the tale to the next, one element is always rendered intact. Viewing the apparently less-than-seaworthy vessel as it embarked, accompanied by a full complement of his parishioners, the Reverend John Davenport is remembered to have spoken prophetically. In direct sight and hearing of the on-board crew and passengers, he is said to have uttered these words in prayer: “Lord, if it be thy pleasure to bury these our Friends in the bottom of the Sea, they are thine; save them!”

The men and women who watched the departure of the ship from the shore saw it slip away unpromisingly into the quickly thickening fog. Months passed and no word of the ship’s arrival in England or sighting of it on the high seas came back to New Haven. With each successive ship that entered New Haven harbor without tidings of the vessel’s whereabouts, the colonists gradually lost hope, sought to cope with their loss and began to pursue other means of making do economically.

An Apparition Appears in the Sky

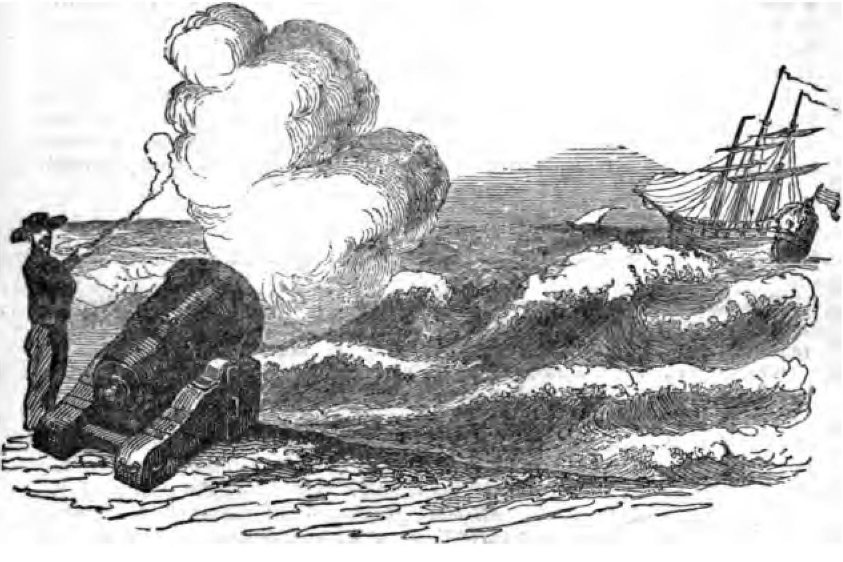

One and a half years after the ship set sail (some versions of the story suggest that only six months had passed), the ship once again became the focus of speculation. A particularly wild summer thunderstorm hit New Haven harbor, and in its immediate aftermath spectators claimed to have seen a vivid phantom version of the ship sailing in the sky, its masts battered and its sails torn in the violent storm.

Vision of the Phantom Ship, painted by Jesse Talbot in 1850, recalls the Great Shippe, a New Haven vessel lost at sea in 1646 – New Haven Museum

The New Haven residents massed along the shore knew at once what had happened. In the spirit of their pastor’s odd “benediction,” they read God’s wrathful judgment into the loss of the vessel—and its spectral return. Had they pinned too much hope on the prospect of commercial success? Had they failed to create the sort of Godly existence in the New World that they had set out to build? The ship never did return, and it took several decades for New Haven to build up its trade and evolve into the bustling New England seaport it eventually became.

Early Folktales Reveal Anxieties of Frontier Life

Successive generations of Connecticut storytellers are likely to have understood and presented the story differently than their early colonial counterparts. Today, the providential implications it once had may strike us as quaint. But to New England Puritans, who often read unusual weather events and other phenomena as indications of God’s awesome power, judgment, and mercy, it was only logical to see a divine message in the unusual skies above New Haven that day.

What adheres is the tale’s rootedness in a specific set of historical circumstances that fore-grounded the anxieties and vulnerability of the first generation of Europeans to settle permanently in Connecticut. In fact, the tale of the Ghost Ship is one of dozens of its type from the pre-Revolutionary era. In such tales one sees how a community’s lurking fears—coupled with the occurrence of an extreme climactic event in a topographically precarious location—inspired bewildered and awestruck eyewitnesses to find supernatural explanations for unusual events.

Michael Hoberman teaches American literature and folklore at Fitchburg State University in Massachusetts and is the author of three books on New England history and culture, including, most recently, New Israel/New England: Jews and Puritans in Early America (University of Massachusetts Press, 2011)