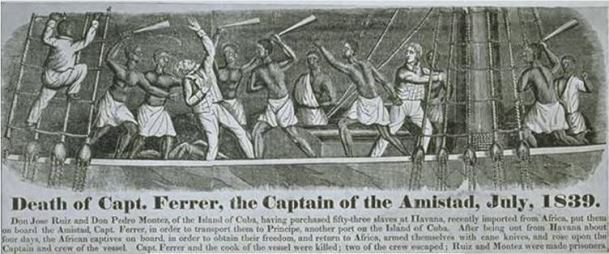

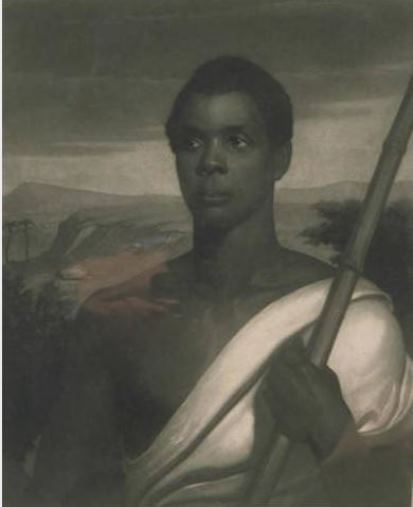

In early 1839, Portuguese slave hunters abducted a large group of African people in Sierra Leone and transported them aboard the slave ship Tecora to Havana, Cuba, for auction to the highest bidder. Two Spaniards, Don Pedro Montez and Don Jose Ruiz, purchased 53 of the captives (members of the Mende people) in Havana and loaded them aboard the schooner Amistad for a trip to a nearby plantation. Just three days into the journey, however, the would-be enslaved people revolted, when 25-year-old Sengbe Pieh (known as Cinque) escaped from his shackles and set about releasing the other captives.

John Sartain, Cinque, chief of the Amistad captives, New Haven, ca. 1840, engraving, 1931.13.0 – Connecticut Historical Society

The Mende killed members of the ship’s crew, including the captain, and ordered Montez and Ruiz to sail for Africa. The ship sailed east during the day, using the sun’s position to determine its direction, but at night, the slave traders quietly redirected their course away from Africa. This process continued for over two months until, on August 24, 1839, the Amistad reached Long Island, New York. There the federal brig Washington seized the ship and its cargo.

American authorities charged the Mende with murder, imprisoned them in New Haven, Connecticut, and towed the Amistad to New London.

Local Courts and International Relations

Upon learning of the capture of the Amistad, Spain’s foreign minister argued that the holding of the ship and its cargo constituted a violation of a 1795 treaty between the United States and Spain, and he demanded their return. Fear of inflaming relations with Spain induced President Martin Van Buren to acquiesce, but Secretary of State John Forsyth stepped in and explained that, by law, an executive, such as the president of the United States, did not have the power to interfere in judicial proceedings. The American court system needed to decide the fate of the Mende captives.

Gravestone of Foone, one of the Africans from the Amistad, Riverside Cemetery, Farmington, 1960-1969. 2001.61.3 – Connecticut Historical Society

At a US Circuit Court trial in Hartford, a judge ruled in favor of dropping murder and conspiracy charges against the enslaved Mende, but felt that competing property claims filed by the Spanish, as well as the crew of the Washington, fell under the jurisdiction of the Federal District Court. A district court judge then ruled that, as former free men living in Africa, the Spanish had no right to enslave the Mende. He ordered the captives released and returned to Africa. Once again, however, considerations of international diplomacy complicated the case. Under pressure from the Spanish government, Van Buren’s administration ordered an appeal to the US Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court began hearing the case in January of 1841. American abolitionists rallied to the defense of the Mende, raising money to hire future Connecticut governor Roger Sherman Baldwin and former US president John Quincy Adams to represent them in court. Arguing in favor of the basic rights of human beings, Adams and Baldwin convinced the court to set the Mende free. The decision came in March of 1841, and later that year, five American missionaries and the 35 remaining Mende (18 having died at different stages of their voyage or while in prison) sailed for Sierra Leone.