By Rafaele Fierro

On a beautiful late-August night in 1910, a crowd gathered at 10 Howe Street in New Haven to celebrate. Mayor Frank Rice and his wife were in attendance as were other politicians along with corporate heads, lawyers, and doctors, all come to celebrate Sylvester and Rosa Poli’s 25th wedding anniversary. The New Haven Evening Register called the gala event “one of the handsomest entertainments ever given in the city.” The Polis turned their lawn into “enchanted gardens with hundreds of Japanese lanterns” and an orchestra played music into the wee hours of the morning.

Entertainment Entrepreneur

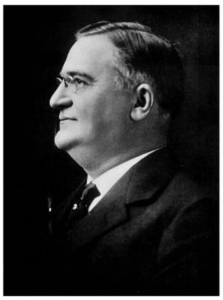

Sylvester Poli

Even though Sylvester Poli had, by 1910, become a highly recognized and respected entrepreneur, he was just at the beginning of his long and successful career. Ultimately, he owned 28 vaudeville and movie theaters throughout New England, including Waterbury’s Palace Theater and New Haven’s Bijou Theater which he created. He built other movie houses that each seated well more than a thousand people in cities known for their blue-collar character: Bridgeport and Hartford in Connecticut; Worcester, Massachusetts; and Scranton, Pennsylvania. It is no wonder, then, that his anniversary brought together so many—more than 100 in all—from New Haven and beyond.

Oak Street, in New Haven’s working-class Italian section, was just around the corner from the Poli’s celebration on Howe Street. Though that neighborhood stood in marked contrast to the evening’s festivities, no walls or gates segregated the poor from the affluent Poli, a self-described commoner who had come to America with virtually nothing. He enjoyed living among the working poor. They worshipped together at St. John’s Roman Catholic Church, a short distance from his home. Poli, moreover, understood that his clientele, the people who made him what he was, often were not men and women of means. Movie-going in the first half of the 20th century tended to be affordable even for those with little disposable income. (It cost about 25 cents to see a film as late as the 1930s.)

The New Haven businessman’s ascendancy into the theater business occurred just as industry burgeoned in Northeastern cities. The region’s many industrial factories attracted thousands of immigrants who found the hours long and the wages short. For many, the better life they had imagined had not panned out. Factory work proved long, difficult, and grinding. Conditions were sometimes deplorable.

Movie-going offered the urban masses a brief respite from life’s daily toil. Poli viewed himself as their guardian, offering an outlet that bound members of his community together and provided a powerful antidote to the crime and poverty plaguing poor neighborhoods. Not surprisingly, garage owners, carpenters, and clerks mingled alongside the politicians, lawyers, and businessmen at the Poli’s 1910 anniversary party.

Combating Prejudice Against Immigrants

Few Yankee names appeared on the guest list, however. Yankees generally found Poli’s ethnicity reprehensible, but his connection to vaudeville—a new form of marketable entertainment they derided—made him even more contemptible. According to historian Douglas Rae, the near universal admiration for Poli reflected the decline in status of the New England old guard. The Yankee elite perceived their culture as “progressively diminishing,” due in large part to the increasing numbers of immigrants who’d come to US shores since the 1870s. It is not a coincidence, for instance, that Yale graduate and eugenicist Madison Grant published his Passing of the Great Race in 1916, around the time that Poli and other recent immigrants rose to power.

To many Yankees, the entrepreneur symbolized a rapidly changing New England—and not for the better. For his part, Poli proved adept at traversing class, ethnic, and cultural lines. His involvement in diverse civic groups and his commitment to the local immigrant community earned admiration. In 1915, for example, the Italian-language newspaper Il Corriere del Connecticut and the New Haven Times-Leader reported extensively on Poli’s efforts, which not only underscored his heavy involvement in the Italian community but also undermined Yankee charges that Italians exhibited conflicting national loyalties. As time went on, Poli’s attachment to the working poor strengthened and his desire to help overcome negative stereotypes deepened. During the First World War, he helped establish a National Guard Company of young Italian soldiers who proved their American patriotism by joining the 2nd Infantry Regiment. Later, during the Great Depression, he organized a benefit in collaboration with the Jewish Welfare Society and the New Haven Register to aid the city’s poor.

The theater magnate’s popularity even overcame the Italian North-South cultural divide that existed on both sides of the Atlantic. While a solid majority of the state’s Italians hailed from southern Italy, Poli himself came from Tuscany to the north. By the start of the 20th century, Connecticut’s northern Italians had formed an organization called the Northern Italian League to distinguish themselves from southern Italians—and to make sure that Yankees understood the vast cultural differences between the two groups. Yet, few cared from where in Italy Poli came.

End of an Era

The great theater mogul retired in 1934, after which time large companies, including the Loew’s Group, began purchasing his establishments. Others were torn down or remade into restaurants. A few remain; most have since disappeared. New Haven’s urban renewal projects of the 1950s and ‘60s saw to the destruction of most of the properties on Howe Street, Poli’s home included. In their place developers built North Frontage Road.

Poli did not live to see his home’s destruction. He died in 1937, arguably the worst year of the Great Depression. Ironically, at the same time, movie-going became more popular than ever—this time as an escape from the cruel world of economic calamity.

Dr. Rafaele Fierro is an Associate Professor of History at Tunxis Community College in Farmington, Connecticut, and is the son of Italian immigrants.