By Richard DeLuca

One of the duties of the colonial post rider was to act as a guide for travelers he might encounter along his route. At the start of the 18th century such travelers were rare, and travel time slow due to the difficulty of the crude and unmarked paths that passed for roads. Nonetheless, a Boston woman named Sarah Kemble Knight made just such a journey in 1704 from Boston to New York over the lower post road.

Madam Knight was a 38-year-old married woman and keeper of a boarding house in Boston with some experience as a copier of legal documents. She was on her way to New Haven (and later to New York City) to act on behalf of a friend in the settlement of her deceased husband’s estate. Fortunately, Knight kept a journal of her trip, and it provides us with one of the few first-hand-accounts of travel conditions in Connecticut during colonial times.

“we mett with great difficulty”

Knight chose to travel with a post rider or other reliable guide, so she was never alone on the road. Still, the difficulties she encountered speak volumes about the physical dangers of long-distance travel by horseback in that era. In crossing the Thames River in a ferry boat that carried both passengers and their horses, she wrote in an entry dated “Thirsday, Octobr ye 5th”: “Here, by reason of a very high wind, we mett with great difficulty in getting over—the Boat tos’t exceedingly, and our horses capper’d at a very surprizing Rate, and set us all in a fright.”

The following day, after traveling for miles over roads that were “very bad, incumbered with rocks and mountainous passages,” Sarah Knight came to “a bridge under which the river ran very swift, my horse stumbled, and very narrowly escaped falling into the water, which extremely frightened me.”

Food and Lodging Inconsistent at Best

As for room and board, Sarah Knight was fortunate to spend one evening with the Congregationalist minister in New London, “where I was very handsomely and plentifully treated and Lodg’d.” The minister, she noted, was “the most affable, courteous, Genero’s and best of men.”

Such experiences, however, were offset by others less wholesome. In Saybrook, where Madam Knight stopped for a mid-day dinner, she complained of the landlady: “Shee told us shee had some mutton wch shee would broil, wch I was glad to hear; […] but it being pickled and my Guide said it smelt strong of head sause, we left it, and pd sixpence apiece for our Dinners, wch was only smell.”

Further on, at a public house in Fairfield, Ms. Knight was likewise unable to eat the meal prepared for her and went to bed supperless. On being shown to her room, “a little Lento Chamber furnisht amongst other Rubbish with a High Bedd and a Low one […] down I laid my poor Carkes (never more tired) and found my Covering as scanty as my Bed was hard.”

Knight persevered and after six days on the road arrived in New Haven, where she visited with relatives before resuming her trip to New York, which took an additional three days of hard travel.

Journal Also Reveals Racism of Time

Despite her adventuresome spirit, Sarah Knight was a woman steeped in the views of her time. Some passages reveal her racial biases—and, for readers today, her words are both difficult and painful to regard. For example, she found Connecticut’s Native Americans to be “the most salvage [savage] of all the salvages of that kind.” As for African Americans, she thought Connecticut farmers “too Indulgent … to their slaves: sufering too great familiarity from them, permitting ym to sit at Table and eat with them, (as they say to save time,) and into the dish goes the black hoof as freely as the white hand.” Such remarks remind us of the complex humanity of the men and women who lived our history. They remind us, too, that prejudices have shaped society in every age.

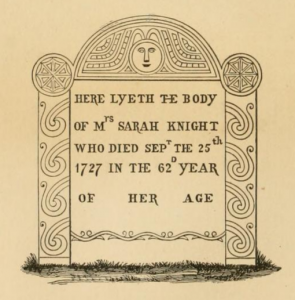

Illustration of Sarah Knight’s tombstone

Journey’s End

In the widowed years of her life, Sarah Kemble Knight left Boston for good and moved to New London to live near her married daughter. There, she owned a tavern and an inn, engaged in the buying and selling of land for speculation and became a respected member of her church. Sarah Knight died at age 62 and is buried in New London.

Richard DeLuca is the author of Post Roads & Iron Horses: Transportation in Connecticut from Colonial Times to the Age of Steam, published by Wesleyan University Press in 2011.