by Andy Piascik

When Emile Gauvreau grew up in Connecticut in the early years of the 20th century, newspapers were king. Radio and television were far in the future and most everyone would have scratched their heads in bewilderment at the words “social media.” It was through newspapers that information of a sort was disseminated and it was from newspapers that millions of Americans learned of events and people beyond their own experience.

Emile Gauvreau was born in Centerville in 1891. As a young boy, a freak accident left him deformed and with a permanent limp. Though he never finished high school, Gauvreau went to work at the New Haven Journal-Courier as a reporter while still a teenager. After almost a decade at the Journal-Courier, the Hartford Courant hired Gauvreau, at 28, to be their managing editor—the youngest person to hold that position in the paper’s long history.

The Hartford Courant

Gauvreau attacked his job with great enthusiasm and spearheaded a number of investigative reporting campaigns. He utilized offbeat techniques and encouraged the reporting staff to do likewise. In one instance, Gauvreau had a Courant reporter work undercover at a veteran’s hospital and write about conditions there from an inside perspective. By 1924, the paper witnessed a dramatic increase in its circulation.

Some of Gauvreau’s campaigns brought him into conflict with Hartford’s political and merchant classes, people like business tycoon and political boss J. Henry Roraback, who pressured the Courant’s owners to control Gauvreau or fire him. The last straw for Roraback, others among Hartford’s elite, and Gauvreau’s bosses was the Courant’s reporting on a medical diploma scam that exposed the laxity of Connecticut’s regulatory laws.

Gauvreau’s participation in the successful effort to preserve Mark Twain’s home on Farmington Avenue also angered the city’s elites, including some in high places at the Courant, who loathed Twain and everything he stood for and had no desire to preserve the legacy of his connection to Hartford. Gauvreau’s strong beliefs and unbending will ultimately cost him his job.

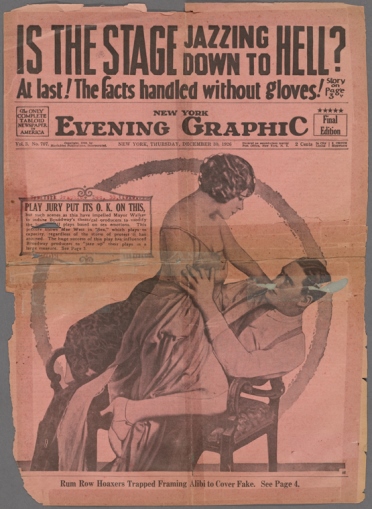

He then went to New York in 1924 in pursuit of a job at the New York Times when he met eccentric publisher Bernarr Macfadden. Gauvreau previously wrote stories for one of Macfadden’s many magazines and Macfadden knew of Gauvreau’s medical scam-busting work. Macfadden, looking to enter New York’s tabloid fray, convinced Gauvreau to be his new paper’s editor. The paper was the New York Evening Graphic.

The Tabloids

The first of the American tabloids was the New York Daily News. It proved phenomenally successful and newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst started his own tabloid, the Daily Mirror, around the time the Graphic started. Like the News and Mirror, the Graphic featured expansive sports coverage, stories about the seamier side of life, and gossip columns about New York nightlife featuring the exploits of the rich and famous. Walter Winchell and future television personality Ed Sullivan were two of its columnists.

Whatever its similarities to other tabloids, the Graphic under Gauvreau was in a league of its own in its coverage of scandal and its prominent use of photos of scantily clad young women. When there was not enough sordid news, Graphic reporters and photographers staged photos and stories of debauchery that ran in the paper as legitimate news. Not long after its founding, the paper earned the nickname, the Porno-Graphic.

Fierce competition in the tabloid market forced Gauvreau to surrender virtually all remnants of the serious journalism he previously employed in New Haven and Hartford. He received a handsome salary during his five years at the Graphic, as well as Graphic stock Macfadden allowed him to buy at a reduced rate. When he quit in 1929 after a falling out with Macfadden, it is said that Gauvreau cashed that stock in for $70,000.

Gauvreau went to work for the Mirror and adopted the credo, “90% entertainment and 10% news.” He wrote a novel, Hot News, in 1931 that became the basis for the movie Scandal for Sale, as well as an autobiography. Gauvreau eventually lost his job at the Mirror when he wrote a book about the Soviet Union that outraged Hearst as insufficiently critical. He worked at a number of jobs thereafter, though never again at a newspaper, and died in Virginia in 1956.

Bridgeport native Andy Piascik is an award-winning author who has written for many publications and websites over the last four decades. He is also the author of two books.