By Brenda Milkofsky

In 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed west from Spain seeking a water route to the spice markets of India. Instead, after weeks of sailing, he encountered a sea full of islands that he named the West Indies. This large group of mostly volcanic islands lies between Florida and the coast of South America. As Spain declined in power, other European nations rushed to establish colonies on even the smallest islands. Colonizers hoped to obtain exotic or valuable raw materials for sale in Europe and to open new markets on the islands for European manufactures. England, which began settling the North American mainland in 1607, joined her neighbors in planting colonies in this Caribbean Sea of opportunity. Connecticut, along with other New England colonies, slid quickly into the slipstream of British trade and became an important player in a new international system of commercial exchange.

Colonists Begin West Indies Trade

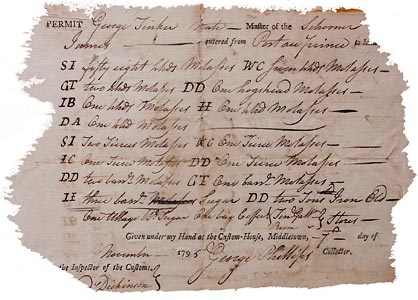

On a Triangle Trade voyage, the schooner James delivered molasses from what is now Haiti to Middletown in 1795 – Connecticut River Museum

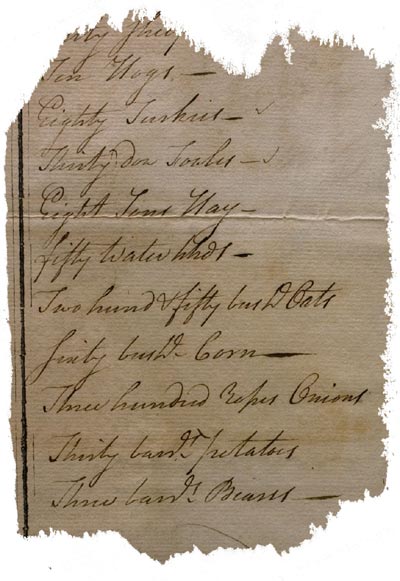

The brig Matilda carried goods from Connecticut to Martinique in the West Indies in 1795 – Connecticut River Museum

By the late 1600s, the beaver and other fur-bearing animals that had been the foundation of Connecticut’s trade with England had all but disappeared. Farmers sought markets for their products from field and forest so they could purchase English cloth, tools, and other essential domestic goods. Because farmers all over New England engaged in growing many of the same crops and raising similar livestock, they needed to find an outlet beyond the region’s shores.

In 1649, merchants from Wethersfield and Hartford invested in the building of a small vessel, the Tryall, to make a “trial” of trading with the English island of Barbados, which had been settled in 1627. The Tryall sailed out of the Connecticut River loaded with fresh farm produce, lumber, and barrel staves (the vertical wooden slabs that when bound together with hoops form the barrel). From this small beginning, a prosperous trade developed between Connecticut and the islands of the West Indies. Customs records indicate that the trade relationships between colonial Connecticut and the populous English islands of Barbados and St. Kitts were particularly strong.

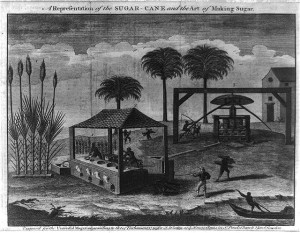

The success of this trade between mainland North America and the West Indies was based on the introduction of sugar as the islands’ primary crop. Sugar is native to Polynesia and was brought from the Canary Islands to the West Indies by Columbus on his second voyage. Tobacco and cotton were tried as cash crops, but they did not do as well as sugar.

Everybody Wants Sugar

The demand for the sweetener in England and elsewhere was tied to the introduction of tea, coffee, and cocoa—all bitter without sugar—to public venues and private houses. The dramatic rise in sugar use and the prices it commanded on the market led island planters to devote their land to sugar cane cultivation instead of growing their own food or raising their own livestock. They cut down forests to plant the canes and erected forts to protect their harbors from foreign powers. This concentration on one crop meant that the islands had to import much of what they needed by water; New England was not that far away.

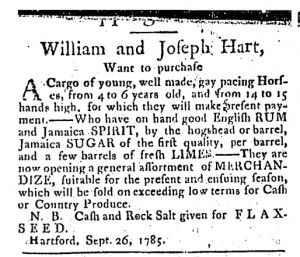

Connecticut merchants kept this trade in motion. They collected “country produce” from outlying farmers at their stores in exchange for imported goods: English cloth, iron, glass, and crockery; East Indian silk, tea, and spices; and West Indian sugar, molasses, rum, salt, fruit, and coffee. Local shopkeepers in Connecticut’s small towns traded with merchants in the larger cities, such as Hartford, Middletown, New London, Norwich, and New Haven, or directly with importers in New York or Boston. When they had collected enough produce to fill a vessel they hired a captain and sent a ship to islands where they had agents, family members, or friends who assisted in disposing of the cargo and locating enough island products to return home with a full hold.

On October 25, 1795, when the brig Polly & Betsey sailed from the port of Middletown to Jamaica, the two-masted vessel carried a Connecticut cargo typical of the island trade. On board, according to the manifest, there were barrels of salted beef and pork, shad, and pickled codfish. There was cheese, butter, beans, potatoes, corn, onions, and apples. Next listed were barrel staves, hoops, hoop poles, lumber, shingles, and oak planks. The live animals included 314 geese, 40 turkeys, 5 hogs, and 200 sheep. The Polly& Betsey did not list large animals on the manifest, but every year between 1796 and 1820 an average of 500 cattle were shipped to the West Indies “live on deck” from Connecticut River ports. Captains were required to carry enough water for the live animals and hay if they were transporting livestock. Over-burdened vessels, hurricanes, yellow fever and seizures by foreign flags were perils of the trade.

Advertisement, Connecticut Courant, 1785

The ship captain, who generally made two voyages a year, was responsible for the safety of the ship and the crew but also the profitable sale of the cargo. Working for different merchants, a captain would go once after the fall harvest and again in the spring after the harbor ice thawed. A voyage took from two to five weeks depending on the weather and port of call. Often, the ship’s commander had to visit several islands to sell the entire cargo. A profitable voyage depended on unknown market conditions, speed of delivery, local contacts, safe passage through often-fierce storms, fair prices, and reputable products. All of this was accomplished without benefit of sophisticated navigational methods or even good communication beyond the news shouted between passing ships.

Vessels for the West Indies trade provided work to sawmills, shipbuilders, sail and rope makers, shipyard workers, and farmers. The latter often supplied not only the cargoes but also the ship timbers and labor, such as hauling. Although a few three-masted ships were engaged in the trade, smaller vessels were preferred. Vessels in this trade ranged from 90 to 150 feet on deck. Too large a vessel took weeks to locate adequate return cargo and fully load.

Slaves and Trade

On nearly every island, the ship captain found vast estates powered by enslaved Africans who produced sugar for export. Huge wooden rollers crushed the canes, and the juice was cooked down to a coarse brown sugar called muscavado and its waste product, molasses. Island distilleries also made a quality rum that was the source of the planter’s profits.

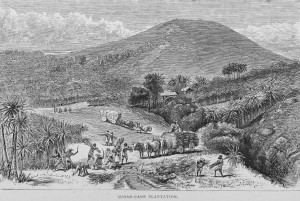

Sugar Plantation probably in the West Indies, 1749 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Sometimes slaves were part of the return cargo to Connecticut along with coffee and tropical fruit, but the real object of the trade was sugar and molasses for New England’s rum distilleries. Of the approximately 5,000 slaves in Connecticut at the time of the Revolutionary War, most came to the colony through the West Indies Trade. Between seven and nine million enslaved Africans were brought in chains to the Caribbean beginning in about 1530 to work in hot, humid fields and the dangerous boiling houses where the juice was cooked to crystal.

During the Colonial period, Britain tried to control the West Indies trade and her mainland colonies. Through the various Navigation Acts, the Molasses Act (1733), and the Sugar Act (1764), the Crown aimed to prevent trade and smuggling with non-British Islands and raise revenue. Some historians contend that the powerful West Indies lobby in Parliament, made up of British bankers who held the debt of the planters, was behind the punitive acts.

During the American Revolution, New Englanders raided island forts to seize valuable cannon, powder, and shot. Some West Indian assemblies opposed British policy toward their North American colonies for fear that they, in the islands, would starve without the corresponding trade; but none officially joined the fray.

The End of Trade

During the first quarter of the 19th century, a series of events and circumstances brought the West Indies trade to a slow, agonizing end. The continued threat and reality of slave rebellions in the islands made for a very high cost of maintaining British soldiers there. The debt of island planters to British bankers grew as the productivity of their exhausted soil declined. Bankers in England found other, more reliable investments, such as railroads, canals, and the new, steam-powered factories.

In the United States, President Thomas Jefferson ordered the Embargo of 1807, which prohibited US ships from leaving American ports. The embargo’s advocates hoped that the measure would help the US avoid being drawn into the war between Britain and France and also prevent the capture of US vessels. This strategy, however, caused financial ruin for many in maritime communities, including those of Connecticut.

Abolitionist forces in Britain made the slave trade illegal in 1807 and emancipated people held as slaves in British possessions in 1834. Freed people might work as freemen on their former plantations, but they also began to grow their own food in corner plots. The infrastructure of the trade collapsed, and plantations stopped improving their facilities with imported lumber and no longer feed their now-freed workforce with imported food. The development of the sugar beet as an alternative sweetener took many Central European customers out of the market.

The Web of Slavery

The West Indies trade was based on captured and enslaved Africans forced to work in agricultural slavery on the sugar islands. Many people in Connecticut profited from this trade, from the ship-owning merchant to the milkmaid who traded her cheese for sugar at the country store. Farmers expanded their cultivated fields and sent their sons to Yale with profits from the trade, and shipbuilding, which became a major industry, used the West Indies trade for research and development.

West Indies sugar-cane plantation – New York Public Library Digital Gallery

In 1776, Connecticut served the Continental Army as “the provision state” because her merchants were experienced at finding and moving farmers’ cattle, produce, and other critical supplies over long distances. Agriculture and the maritime trades were the handmaidens of Connecticut’s early economy and provided stability so that self-government might also flourish.

Today, much of the state’s remaining early architecture survives from this period because quality materials were used by experienced builders and architects to create substantial homes for people who grew wealthy in the trade. Furniture makers, portrait painters, and even clothiers created enduring works of art on commissions from these merchants.

Brenda Milkofsky curated the exhibition A Grand Reliance, The West Indies Trade in the Connecticut Valley while Director-Curator of the Connecticut River Museum in Essex, CT.