Zebulon Brockway was one of the more successful and controversial figures in prison reform during the 1800s. While advocating a program designed to educate and reform prisoners rather than punish them, his sometimes unorthodox and brutal administrative style ultimately brought an end to a 50-year career full of innovation. Listed among his achievements is the promotion of indeterminate sentencing, as well as the development of the precursor to the modern parole system.

Zebulon Brockway was born in Lyme, Connecticut, in 1827. Pursuing an interest in criminal behavior and correctional facilities, at the age of 21 he went to work as a clerk at the Wethersfield Prison. The years that followed afforded him the opportunity to serve as a superintendent of the Albany Municipal County Almshouse in New York (where he formed a belief in criminal behavior as a treatable “disease”) and then, in 1854, as superintendent of the Monroe County Penitentiary in Rochester. While in Rochester, Brockway began efforts to reform youthful offenders—those, he thought, with the greatest potential for turning their lives around.

Progressive Views Included Training for Prisoners

In 1861, Brockway moved to Detroit to head the Michigan House of Corrections. Here he introduced education to prisoners aged 16 to 21 and developed a system for providing prisoners with vocational skills and rewarding them for good behavior. To Brockway’s dismay, however, Michigan failed to pass legislation that allowed him to fully realize his system of indeterminate sentencing—a system that rewarded prisoners by potentially shortening their sentences for good behavior.

Brockway recognized the opportunity to realize his system with the opening of the Elmira State Reformatory in New York in 1876. The prison focused on rehabilitating first-time offenders ranging in age from 16 to 30, and Brockway, now famous for his reforms, accepted a position to operate the new facility.

Mixed Record at Elmira State Reformatory

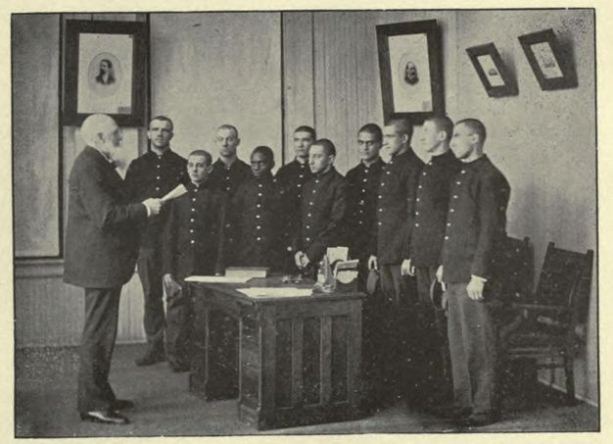

Over the next 25 years, Brockway made Elmira a study in prison reform. Prisoners worked during the day and, at night, received education or vocational training. Brockway allowed prisoners to earn “points” by learning technical skills or completing educational assignments and religious programs. The accumulation of sufficient points led to early release through a formalized parole program.

Birthplace of Zebulon Brockway, Brockway’s Ferry, Lyme from Fifty Years of Prison Service by Zebulon Reed Brockway

Brockway’s efforts, however, were not without criticism. Reports coming out of Elmira detailed a military-style discipline within the prison and punishments for misbehaving prisoners that included flogging and being handcuffed to walls while in solitary confinement. In 1893 the state began investigating Brockway’s alleged excesses and poor administrative abilities, ultimately resulting in Brockway’s resignation in 1900.

Brockway spent the remaining years of his life chronicling his efforts at reform. In 1912 he published his autobiography detailing his years in the American penal system and he continued to defend his methodology and promote his vision of prison reform right up until his death in 1920.