Written in December 1791, the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution states, “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.” Since its authoring, this amendment has been the subject of frequent interpretation and argument. For some, gun ownership is central to the rights and responsibilities of US citizenship; for others it is an anachronism dangerously out of step with current social and technological realities. This controversial and divisive topic assumed a new and tragic place in Connecticut history after the horrific mass shooting of 20 children and 6 adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown on December 14, 2012. A longer look at state history shows us that Connecticut has other connections to the gun debate, particularly in the formation of The Gun Control Act of 1968.

From Norwich to Yale to Washington, DC

Thomas J. Dodd placed himself in the forefront of the debate when he represented Connecticut in the United States Senate in the 1960s. Born in Norwich in 1907, Dodd graduated from Providence College in 1930 and earned his law degree from Yale Law School in 1933. He worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the National Youth Administration in the 1930s and was an assistant to the United States Attorneys General from 1938 to 1945. One of Dodd’s most notable accomplishments was serving as Executive Trial Counsel in 1945 and 1946 for the United States’ prosecutorial team at the Nuremberg trials, which held Nazi war criminals accountable after World War II.

Dodd served in the US House of Representatives, representing Connecticut’s first district, from 1953 to 1957 and in the US Senate from 1959 to 1971. As a senator, one of his signature causes for which he relentlessly fought was that of gun control. As early as 1961, as Chairman of the Juvenile Delinquency Subcommittee, Dodd was speaking out about the need for greater regulation, citing the problem of violence on television and rising levels of gun violence, particularly as it affected young people.

First Efforts to Regulate Firearm Sales Meet with Defeat

Dodd broadened his focus to encompass all gun violence and, in 1963, crafted Senate Bill 1975, a “Bill to Regulate the Interstate Shipment of Firearms.” This bill promoted the need for regulation of interstate sales of long guns, dealt with issues of juvenile delinquency and accessibility to firearms, and barred criminals and the mentally impaired from owning guns. Dodd contended that this bill would not render an undue burden to lawful gun owners; in a statement he made to the Senate’s Commerce Committee on December 13, 1963, he said it “ involves no real obstacle to any law-abiding citizen who wishes to purchase a weapon, no more an obstacle than that to operate a bicycle, far less than that required to operate an automobile.” The bill, which Dodd described in a speech given on August 12, 1964, as “unreasonably and unjustly opposed by a loud and well organized hard-core minority,” faced resistance, and it died in the Commerce Committee without a vote ever being taken on it.

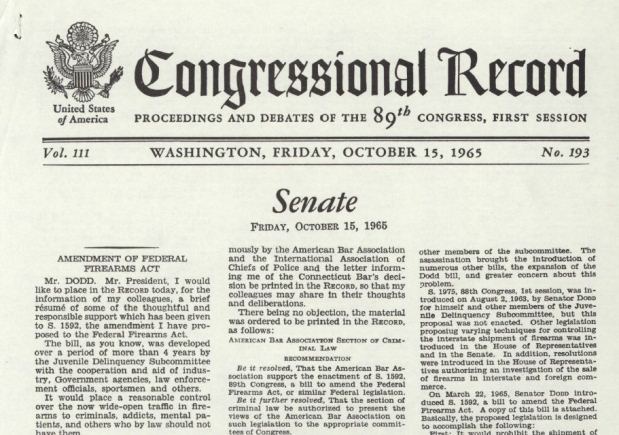

The defeat of S. 1975 did not deter Dodd’s quest for gun control legislation, and he pressed ahead with other bills. Senate Bill 1592, “A Bill to Amend the Federal Firearms Act of 1938,” which Dodd submitted in May 1965 at the request of President Lyndon B. Johnson, sought to control the illicit sale of guns “to known criminals, mental patients, narcotic addicts and others to which local law prohibits the ownership of firearms.” With the encouragement of the National Rifle Association thousands of hunters across the country sent Dodd letters stating their opposition to the bill. Like Dodd’s previous bill, this one died in committee.

Gun Control Act of 1968 Passes into Law

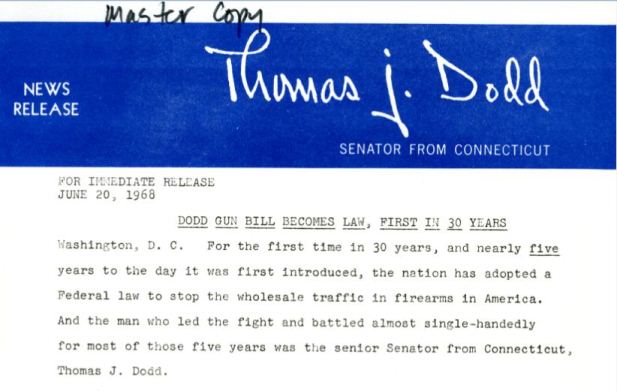

Dodd pressed on. In January 1967 he introduced a similar bill, designed to increase fees and the regulation of firearms dealers and impose a federal minimum age requirement for handguns and long guns. Better known as the Omnibus Crime Control Act of 1968, it passed in the Senate in May 1968 and by the House of Representatives on June 6, the day after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy.

Speech by Senator Thomas J. Dodd in the Senate, as recorded in the Congressional Record, on the Amendment to Federal Firearms Act, October 15, 1965 – Archives & Special Collections of the University of Connecticut Libraries

Other firearms measures were introduced, including the proposal to ban interstate sales of long guns, affixing a serial number on all firearms, and establishing a national gun licensing system, and on October 22, 1968, President Johnson signed the Gun Control Act of 1968. The main objectives of this Act were to eliminate interstate traffic in firearms and ammunition; deny access to firearms to minors, convicted felons, and persons who had been committed to mental institutions; and enact prohibitions on the importation of firearms “with no sporting purpose.”

Dodd’s Congressional papers, held in Archives & Special Collections of the University of Connecticut Libraries, are replete with the many speeches, press releases, passages from the Congressional Record, and memoranda where he spoke out for the need for gun control. The records show he repeatedly spoke to Congress on this issue, citing statistics and examples of the rise in crimes involving firearms in localities across the United States. His passion on the topic shows in every document and aptly illustrates his relentless fight against overwhelming opposition. In October 1968, following the passage of the bill, he wrote “No one can predict how many lives will be spared because of this bill, but, if the bloody record of our yesterdays is any measure, millions of future Americans will live to enjoy the promise of many peaceful tomorrows. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to play a part in this great moment in our time.”

Contributed by Laura Smith, Curator for Business, Railroad, and Labor Collections, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries.