By Patricia M. Schaefer

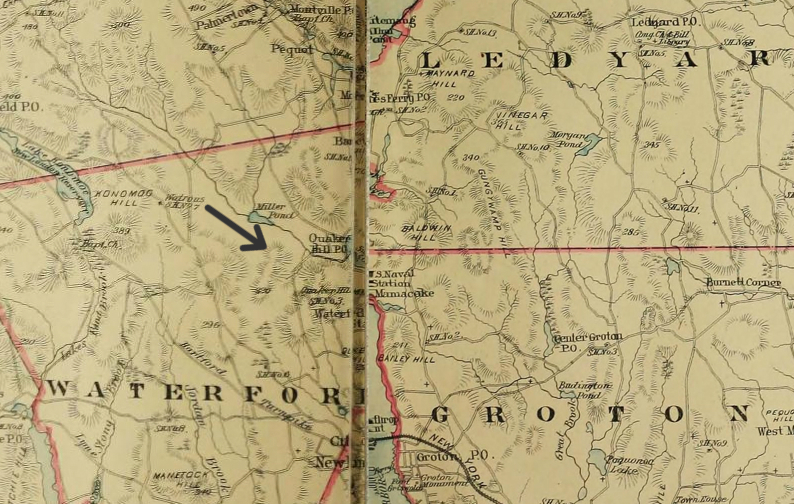

In the towns of Waterford and Ledyard there are neighborhoods known respectively as Quaker Hill and Quakertown. The names are the only remnants of a religious group active in the New London area for about 200 years. Although often referred to as Rogerene Quakers, and sometimes just called Quakers, the Rogerenes had no connection to the Society of Friends founded by George Fox. Instead, they were originally a splinter sect of the Rhode Island Seventh Day Baptists. Founded by John Rogers Sr. in the late 1670s, the sect persisted into the early 20th century.

James Rogers, the father of John, was a wealthy trader and baker, with extensive properties on both the west and east sides of the Thames River in New London. In the mid-1670s he and four of his five sons, both of his daughters, and all their spouses became involved with the Seventh Day Baptists of Newport. John Rogers began to split from that religious body when two of its elders heeded the request of New London town authorities not to baptize a woman in Winthrop’s Cove on a late November Sunday in 1677 but to move the ceremony elsewhere. Rogers refused to compromise, declared himself an elder, and performed the baptism.

Sect’s Beliefs Seen as Controversial by Contemporaries

Refusal to compromise became the governing principle of Rogers’s life. He became a preacher, collected a few followers, and formed a new sect. Some of their beliefs, which were considered scandalous by their more orthodox neighbors, are familiar to us today. Like Baptists, they believed in adult baptism only. Like Christian Scientists, they believed in healing by prayer and not by medicine. And like many mainline Christians, such as Presbyterians and Congregationalists today, they believed that while meetings for worship should be held on Sunday, the rest of the day should be treated like any other. Other beliefs sprang from a literal interpretation of selected Scriptural passages. The Rogerenes believed that prayer should be mental only, not oral, and that Communion, or the Lord’s Supper, should be celebrated only in the evening.

Until the early 1700s, the Congregational Church was the only denomination recognized by the Connecticut government and was supported by taxes. Rogers and his followers believed that there should be no paid ministry—and certainly not one supported by taxes. Neither did they believe in separate buildings for public worship. Their refusal to pay taxes in support of the ministry frequently meant that they paid more than their share, since the constable would take both the original amount and the fine for non-payment when he came to forcibly collect what was due. This went on for many years, to the point where it was difficult to find an officer willing to go to the Rogerses’ Upper Mamacock farm (now called Quaker Hill) to take the requisite cow or other forced payment.

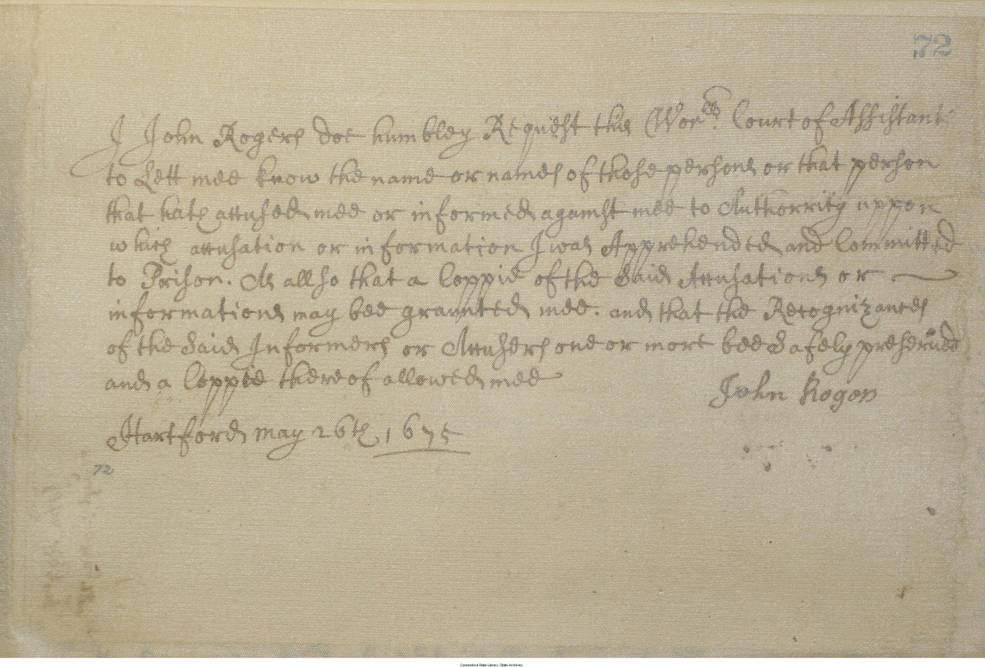

Appeal of John Rogers, May 1675, from the Case of John Rogers – Connecticut State Library, State Archives, RG 000, Samuel Wyllys papers

Agitators for Their Faith

The aspect of the Rogerenes that caused the most trouble for their neighbors was their determination to be persecuted for their beliefs. Rather than simply staying away from a meeting conducted by a paid minister, they would attend and disrupt the service. The diarist Joshua Hempstead mentions Rogerene activity many times in his 48-year-long diary. In September of 1719 he notes that “Jno Rogers & his crew made a disturbance. they…the midst of prayer time. they came in a Horse Cart Commited to prison at night.” Additionally, the Rogerenes would make certain the authorities knew they were working on the Sabbath by making it obvious. In August of 1712, Hempstead wrote, “Sund 24 Jno Bolles was Taken by ye Constable before meeting by david Richards’s in ye highway bringing Poles from Cedar Swamp on horses &c. was kept al night.”

Sometimes, though, the persecution was unmerited, especially in the early years of the sect. In 1695 the New London Congregationalist meetinghouse was burned, and the Stonington meetinghouse was damaged by “daubing it with filth.” Bathsheba (Rogers) Fox, John Rogers Jr., and William Wright, an Indian servant of John Rogers Sr., were all convicted in varying degrees of committing these acts, although the evidence would seem to contemporary observers to be nonexistent. Fox and Rogers were eventually freed. Wright remained in jail with John Rogers Sr. until Rogers was “set at liberty in open court” without conditions put upon his release. Wright was asked to swear that he would “behave himself civilly and peaceably,” including refraining from work on the Sabbath. When he would not so swear, he was transported out of the colony.

The frequency of disturbances depended on who was involved with the sect at the time. There is a 20-year gap in Hempstead’s references to Rogerene activity, from 1725 to 1745, and almost nothing after that. Frances Caulkins, a historian writing in 1852, stated that there was another “outbreak” of disturbances in the 1760s, but that at “the present day they never molest the worship of others, and are themselves unmolested.” Many Rogerenes had become members of other churches by the early 19th century.

What is now Quakertown in the southern part of Ledyard was the home during the mid-18th century of John Waterhouse, a leader within the Rogerenes. A 1904 account of the Rogerene’s history notes that Quakertown believers in the early 1800s began to regard the “blending in” of New London Rogerenes with dismay and determined to bring up their children “in the faith” while “carefully avoiding contact with other denominations.” The group was very active in the abolitionist cause, and between 1830 and 1850 Quakertown was one of the stations of the Underground Railroad.

Peace meeting Burrows’ Grove, Mystic, ca. late 1880s – Mystic River Historical Society, Stinson Collection

By the middle of the 1800s the Rogerenes became firmly anti-war and anti-military. The Quakertown Rogerenes invited Quakers to join them in holding a Peace Convention near Mystic. In August of 1868, the first of an unbroken series of yearly Peace Meetings was held in an attractive grove on a hill by the Mystic River. The meetings were held until World War I, eventually growing to four-day events with an attendance of several thousand people.

However, as the 20th century progressed, the Rogerene community dissolved. Today, the Mystic hill that once hosted their anti-war meetings is a park called the Peace Sanctuary. It is open to the public and cared for by the Denison Pequotsepos Nature Center.

Patricia M. Schaefer is the author of A Useful Friend: A Companion to the Joshua Hempstead Diary, 1711-1758, winner of the 2008 Homer D. Babbidge Jr. Award for the best work on Connecticut history, and writes and speaks on colonial Connecticut.