By Andy Piascik

Waldo Bryant founded the Bryant Electric Company on John Street in downtown Bridgeport in 1888. Beginning with seven employees, the company grew rapidly and moved three years later to its longtime location on State Street on the city’s west side. It was the largest factory in a major industrial hub that also included United Pattern, Bridgeport Organ, Casco, Bassick, American Graphaphone (later Dictaphone), American Bead Chain, and Hubbell. The Bryant plant was situated amidst several populous working-class neighborhoods and many of the company’s employees over the decades lived close by.

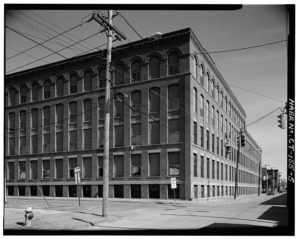

View East-Northeast of Bryant Electric Building #21 – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Bryant Electric acquired several other local companies in its early years and was once Bridgeport’s largest employer with 1,500 workers in 1915. Waldo Bryant sold a majority interest of the company to Westinghouse in 1901, though he continued to run it until 1927.

Workers at Bryant made wiring devices, switches, and electrical components, twelve devices in all at first but that number grew to over four thousand by 1928. For a period of years, Bryant was the world’s largest factory devoted to the manufacture of wiring devices. The company patented a number of items, including the first push-pull switch.

Difficulties of Factory Work

Factory work in the early 1900s was extremely difficult and often dangerous, and wages were low even at prosperous companies like Bryant. Workers struck the plant a number of times over the years, with the first strike of note taking place in 1915. Women assemblers not welcome in the American Federation of Labor’s craft unions led the strike and demanded an eight-hour workday and overtime pay after forty hours. After two weeks, the workers won their demands.

Bryant’s workers elected the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE), a new union affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, as their collective bargaining representative in the late 1930s. They won significant gains in wages and benefits during the Second World War when the company did a substantial amount of work for the military. By this time, the Bryant factory had 340,000 square feet of floor space and its peak workforce of 1,700.

Capital Flight and Job Loss

In the 1970s, Bryant’s parent company Westinghouse began to move Bryant jobs from Bridgeport to North Carolina, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic where the shops had no unions and workers received lower pay. Company executives also became more aggressive at the bargaining table, demanding givebacks in wages and benefits. The UE was more militant than most unions and its members at Bryant organized demonstrations in response. They also participated in a nationwide strike against Westinghouse in the summer of 1976 by which point the Bridgeport factory’s workforce was down to just seven hundred.

View Southwest of Bryant Electric Building #7 Main Office Entrance – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Bridgeport’s industrial decline escalated dramatically in the 1980s and factories with long histories in the city closed their doors while others laid off large numbers of workers who were never rehired. Though waging an ultimately losing battle, Bryant workers responded to rumors of a closure of the plant in 1986 with demonstrations at company headquarters as well as a march down State Street demanding that Westinghouse commit to keeping the plant open.

Family members of workers participated in these actions, along with workers from other factories and community residents who understood the importance of good-paying jobs to the city’s well-being. Owners and employees of restaurants, diners, bars, and other businesses near the plant also supported these efforts, recognizing that their employment was directly linked to Bryant’s. Their concerns proved entirely justified when neighborhood mainstays Junior’s Restaurant, the Flyer Diner, and others went out of business not long after Bryant closed.

In 1987, with the factory’s workforce down to 450, Westinghouse announced the closing of the Bryant plant the following year, exactly one hundred years after its founding. Production ceased for good on April 22, 1988. Bryant’s remaining assets were sold to Hubbell, a longtime competitor with a factory just several hundred yards away. (Hubbell closed its doors several years later.) The sprawling Bryant complex sat empty until it was demolished in 1996. Several businesses now occupy the site including Chaves Bakery, DeYulio’s, FuelCell Energy, and AKDO Intertrade.

Bridgeport native Andy Piascik is an award-winning author who has written for numerous publications and websites over the last four decades and is the author of several books. He can be reached at andypiascik@yahoo.com.