By Anthony Roy

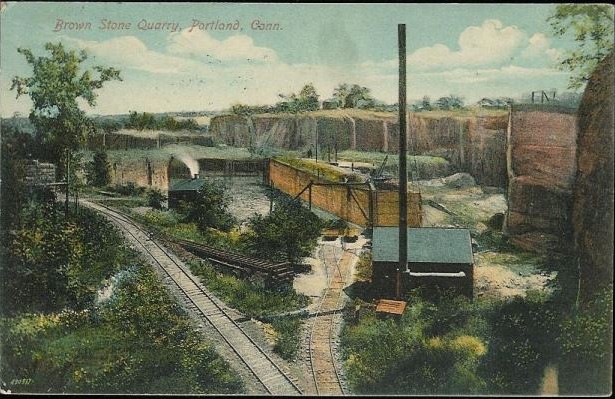

As the hammer strikes the chisel, chunks of brown sedimentary stone burst from their ancient nesting place and scatter upon the shop floor. For hours on end, the master craftsman takes calculated shots at the brownstone soldier. With each blow against the fragile rock, a figure takes shape. The stone is from a quarry in Portland, Connecticut. Its manufacture takes place at 650 Main Street, Hartford. The contractor is Batterson’s Monumental Works, a company owned by political heavyweight and founder of Traveler’s Insurance Company, James G. Batterson. Charles Conrads, a German immigrant and Civil War veteran, is the lead artisan entrusted to hew the rough brownstone into a tribute to sacrifice and unity. This purposefully imperfect sculpture was produced as a prototype. It was the first standing Civil War figure modeled by Charles Conrads and certainly the first such monument in the state of Connecticut.

James Batterson, business owner, politician, entrepreneur, was a true man of his time. Illustration from the Commemorative Biographical Record of Hartford County, Connecticut, Vol. 1, 1901.

Charles Conrads was Batterson’s lead sculptor. Batterson employed Conrads’s genius and imagination to create some of his company’s finest monuments. Born in 1839, the German national was in the process of migrating to Texas to join his family, but a blockade of the Southern states in late 1860 prohibited him from that move. Conrads enlisted in Company G of the 20th New York on March 3, 1861; one day after Texas was admitted to the Confederate States of America, one day prior to Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, and just 40 days before the attack on Fort Sumter. Conrads served 13 months in the New York Volunteers and then 11 months in Battery F of the United States Artillery. As a soldier, Conrads fought in several big battles, including Antietam and Fredericksburg. He was discharged on June 1, 1863, five months after the Emancipation Proclamation. Three years later, Hartford business mogul James G. Batterson employed Charles Conrads as a sculptor.

Conrads was the perfect candidate for the position. In 1858, prior to immigrating to the United States, he received a fine arts degree in “bildhauerkunst,” or sculpture, from the Royal Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts. Batterson, a regionally renowned Egyptologist, hired the sculptor to create monuments capable of rivaling the finest stone memorials around the world. Shortly after his 1866 move to Hartford, Conrads sculpted a model of a Civil War soldier figure. The clay model was a quarter of the size of the twenty-one foot soldier statue commissioned by the Antietam National Cemetery. In 1874, the Hartford Courant declared, “The [Antietam] figure is, we believe, the largest in stone this side of Egypt, and its execution in so hard a material as granite was considered a daring attempt in art. If the verdict of the artistic world is favorable, the result will be a great triumph for American genius and enterprise.” Conrads designed the Forlorn Soldier as an expression of this genius.

An ad for James G. Batterson’s Steam Marble Works from Geer’s Hartford City Directory for 1855-56…

As described in Neither Forlorn Nor Forgotten, Conrads crafted the old brownstone soldier, known as the Forlorn Soldier, as a prototype for a series of identical Civil War soldier statues produced by Batterson’s monument company. The fact that Conrads crafted this soldier from brownstone is significant. The Forlorn Soldier is the earliest of three Civil War soldier figures that Conrads crafted from the sedimentary rock. Granite, a much more durable igneous stone, was the preferred material used in virtually all of Batterson’s other statues. The old brownstone soldier was quarried in Portland, Connecticut, shipped on the Connecticut River, and transported to Batterson’s shop on Main Street, Hartford. Batterson entrusted Conrads to shape the porous block. The sculptor followed a calculated and precise process because the cost of error was very high.

For many decades, the oral history of the old brownstone soldier claimed that people rejected the statue because the wrong foot, the right foot, was forward. It is nearly impossible, however, to imagine that Charles Conrads, an experienced soldier and accredited sculptor, made such a mistake. Surely, Conrads received instruction on the appropriate footing as prescribed in the military drill manual. It is also important to remember that Conrads was a highly capable artist entrusted with all of Batterson’s most important sculptures. Neither Forlorn Nor Forgotten explains that the footing of the soldier intentionally helped balance the statue. Unfortunately, the design proved flawed. The statue was too top heavy and thus unfit for commercial reproduction. Later models included a tree stump to add further support and weight at the bottom of the statue.

Batterson’s stone shop commonly kept the pieces they did not sell. An 1877 Hartford Courant article explained, “facsimiles of past productions are preserved in plaster, clay and photograph.” It is no wonder that the brownstone soldier remained on the Batterson property until Michael and John Kelly rediscovered it in the 1890s. The Kelly brothers resurrected the old brownstone soldier, provided the statue with a pedestal, and showcased the figure on Charter Oak Avenue. It was during the soldier’s sojourn at this site that the brownstone statue befell brutal treatment and developed into a legend. In 1932, the Hartford Courant reported that parts of its face, hands, and musket were already gone and the reporter recorded the “wrong foot forward” myth that ultimately dominated the narrative of the old brownstone soldier for 80 years.

Anthony Roy is a regional historian and social studies teacher at Connecticut River Academy whose work related to the Forlorn Soldier was completed as a part of his candidacy for a master’s in public history from Central Connecticut State University and as a part of the Connecticut Civil War Commemoration Commission’s efforts to study and inspire awareness of the American Civil War and Connecticut’s involvement in it.

<< Previous – Home – Next >>