In 1641 Hartford opened its first jail on the north side of State Street (presently Market Street) where it served the county for almost 100 years. In the mid-18th century, Hartford leaders sold the “prison land,” including the building and its contents, and moved the jail to the “highway” (now Pearl Street). In the decades that followed, Hartford ushered prisoners through a revolving system of different structures until, in 1873, the city finally bought a large parcel of land on Seyms Street for $35,582 and made it the site of the Hartford County Jail.

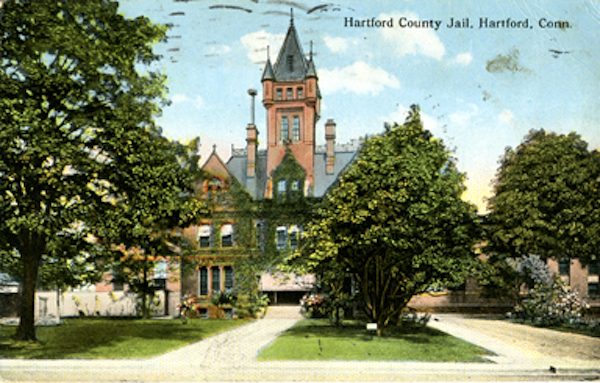

Noted architect George Keller, hired to design the jail, admitted to a lack of prison-design knowledge and promptly set off to travel the country to find inspiration in other prison buildings that were both attractive and functional. He completed a High Victorian Gothic style jail (that later became known as the “Seyms Street Jail”) at a total cost of $175,898. His original design contained 136 cells on four tiers and the jail also offered a smaller three-tier block containing 24 cells. In 1896 builders added a “substantial brick wing” that contained an additional 120 steel cells.

In its earliest days, the jail provided prisoners with straw mattresses but no plumbing or sewer lines, and very little ventilation. The women’s section, located at the west wing, contained 36 cells and women prisoners did the jail’s laundry and mending. In 1904 the Seyms Steet Jail added a large work area to accommodate industry and all men, except those who were too ill or relegated to other departments, worked in the manufacture of chairs under contract with the Connecticut Chair Company.

Deplorable Living Conditions

Despite its years of service to the county, many alleged the Seyms Street Jail actually did more harm to the inmate population than good. The jail had a reputation for operating under miserable conditions, offering numerous sanitary and human rights violations, and it eventually became the subject of legislative scrutiny, lawsuits, and regular protests. In 1915 the legislature formed a committee to investigate conditions at the jail and called upon Sheriff Dewey who testified that the facility desperately needed more modern conveniences, such as plumbing.

In May 1920, Nation magazine published a report that exposed some of the horrific conditions at the jail. The magazine criticized the jail’s “punishment rooms”—four cells that resided directly over the jail’s boiler room. The hot floors burned men’s feet; there were no windows or light, and when confined there the men received only small amounts of bread and water each day. Despite the negative publicity, few improvements came over the years, and in 1938 a state legislative committee continued the criticism of the jail’s largely deplorable living conditions.

In the 1960s both prisoners and students participated in protests demanding improvements. This included a 1967 protest in which 145 inmates launched a sit-in to protest overcrowding, poor food, lack of medical care, and abuse by guards.

Seyms Street Jail Closes

In 1966 the Connecticut General Assembly finally authorized funding for a new jail, but it took another 10 years of negotiating with neighboring towns to finally decide on the facility’s location. The negotiations ultimately kept the prison in Hartford. In 1977, jailers handcuffed 350 prisoners and moved them 12 at a time to the new facility, leaving the Seyms Street Jail empty for the first time in over a century. Authorities tore down the abandoned jail shortly after the new jail opened and, in 1979, the former prison property became Lozada Park.