By Edward T. Howe

The Connecticut poll tax, in its various forms, lasted for almost 300 years (1649-1947). During its use, it encompassed four different variants: the original poll tax, a military commutation tax, a personal tax, and an old age assistance tax. In each case, the state levied a fixed amount on each person liable for payment. The tax, considered regressive, fell disproportionately on lower-income groups.

Original Poll Tax (1649-1909)

In preparation for war, The Articles of Confederation of the United Colonies of New England (1643), which included the Connecticut and New Haven colonial governments, stipulated that “all charges of the war be born by the poll.” Although no war ensued, Massachusetts enacted a law in 1646, which included the first poll tax in the colonies (to help finance colonial and local expenditures).

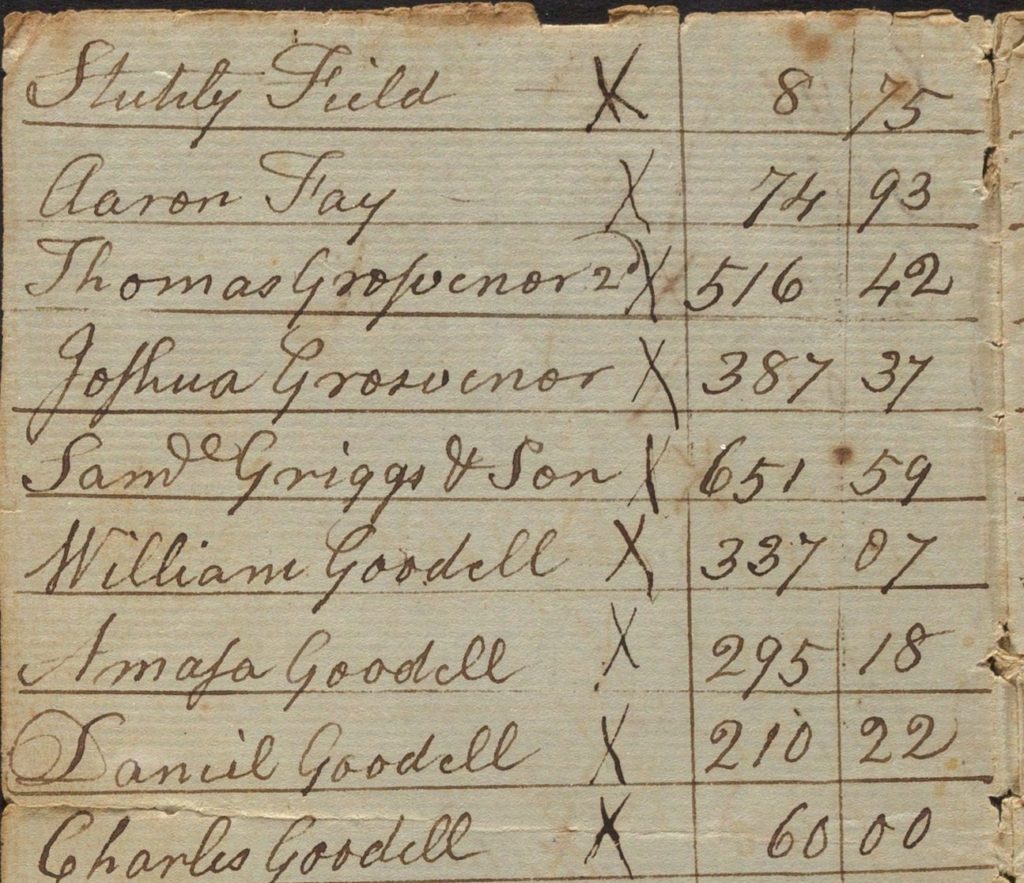

Requests lists of taxable property from residents of Plymouth, 1883. – Connecticut Historical Society, Connecticut Digital Archive

By 1649 the New Haven colony also used a poll tax, becoming the second colonial government to do so. The Code of 1650, Being a Compilation of the Earliest Laws and Orders of the General Court of Connecticut, compiled by Roger Ludlow, specified that all male inhabitants 16 years and older (except magistrates and elders of the churches) faced an assessment of “two shillings sixpence by the head.” By 1651 separate lists of “ratable persons and estates” were drawn up in each town by the assessors in both the Connecticut and New Haven colonies. These lists were forwarded to the colonial government for the compilation of the aggregate value of all taxable property in the colony (known as the “Grand List”).

Local taxes based on the Grand List helped to generate revenue for church, school, and town expenditures. Throughout the colonial era, the combined peacetime poll and property tax burden – payable at times in wampum, “in kind” (vegetables and meat), or money – for colonial and town governments was relatively light, even with compliance problems and numerous exemptions. This system of taxation, with various changes, continued into statehood.

Military Commutation Tax (1847-1909)

Connecticut enacted a second type of poll tax (the military commutation tax) in 1847. It stated that all able-bodied men between 18 and 35 years had to register for military duty, with certain exemptions (e.g., ministers and physicians). All men, intent on avoiding military service, had the opportunity to pay a one-dollar tax in commutation (i.e., replacement) of such duty, which the town treasurer forwarded to the state for the support of the militia. Military personnel were exempt from the poll tax during their period of service and after ten years of service were exempt from payment altogether. For a long time both the poll and military commutation taxes received criticism because of inconsistency between officials in listing those liable for the taxes, uneven enforcement of collections among the towns, and a need for a uniform tax rate to replace the existing levies.

The Personal Tax (1910-1935)

In 1910, the personal tax, enacted as a replacement for the aforementioned taxes, became the third form of poll tax. It stated that every man between 21 and 60 years of age had to pay a tax of

The Personal Tax, enacted in 1910, helped cover the cost of supporting the National Guard. (Connecticut National Guard: Troop B cavalry crossing the Bulkeley Bridge, 1910-1919) – Connecticut Historical Society, Connecticut Digital Archive

two dollars for town and state purposes. City and town officials added the tax to the annual property tax bill of liable males.

Instead of the military commutation tax, 85 percent of the cost of supporting the National Guard came from the towns in proportion to their Grand Lists, with the remainder from state funds not otherwise appropriated. The new tax law eliminated the discrepancy between the one-dollar poll tax and the two-dollar military commutation tax, and reduced the age limit to 60 from the previous poll tax requirement of 70. Revenues subsequently rose as compliance with the new tax law improved. After achieving the right to vote in 1920, women became subject to the tax a year later.

The Old Age Assistance Tax (1936-1947)

The old age assistance tax, the fourth and final version of the poll tax, was enacted during the Great Depression to aid the elderly. The new law replaced the two-dollar personal tax with a three-dollar head tax levied on men and women between the ages of 21 and 46 years. Any person 65 years and older with insufficient means of support, and having no one legally liable to help them, became eligible for an original payment not to exceed seven dollars a week.

Connecticut, facing increasing revenue needs after World War II, abolished both the old age assistance tax and the state tax on towns based on the Grand List and replaced them with the sales and use tax in 1947. Future old-age benefit payments came from the General Fund of the state which relied heavily on new sales tax revenues. Thus, after providing the state and (to a lesser extent) localities with a source of revenue for almost 300 years, the poll tax finally passed into Connecticut history.

Edward T. Howe is a Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at Siena College near Albany, New York.