A number of prominent artists called Bolton home in the 18th century. One of the more unique among them was stone carver Gershom Bartlett. His distinctive flair for carving cemetery headstones adorned with round faces, which appear cartoonish to modern eyes, made him a fixture of early New England culture. Bartlett was the first gravestone carver in the upper Connecticut River Valley, and his headstones tell historians much about early life in the northeastern colonies.

Gershom Bartlett was born in Northampton, Massachusetts—his great-grandfather having arrived there from England just 60 years earlier. Historians believe Gershom’s father, Samuel, was a stone carver. The distinctive style of Samuel’s gravestones—an arched top with square “shoulders” and a carved line that echoes and accentuates the top arch—appears on numerous Bartlett family gravestones. This style disappears from Northampton around 1725, only to emerge in Bolton where Samuel moved his family that same year.

After growing up in Bolton, Gershom moved to Windsor where he worked at least part-time as a farm laborer. After his father’s death in 1746, Gershom married and began dual careers in land speculation and gravestone carving. He made his first stones, dated 1747, out of sandstone from Windsor, but by 1751, he was back in Bolton. The town of Bolton provided ample deposits of schist for the aspiring stone carver. For the next 20 years, Gershom Bartlett’s production averaged approximately 30 headstones per year. In fact, Gershom carved the bulk of his career’s work—over 700 stones—from the local Bolton schist.

Historical Records in Stone

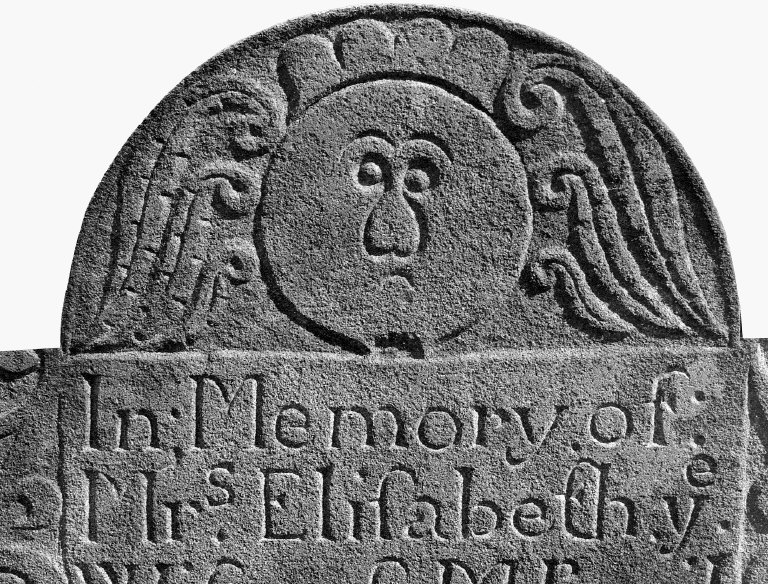

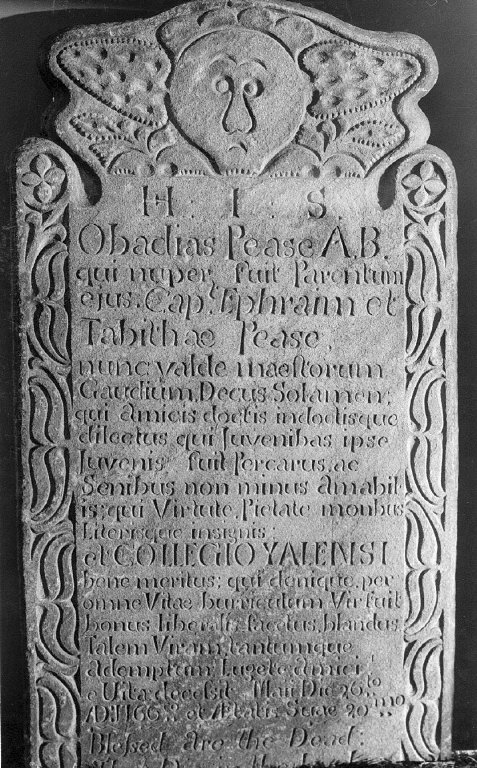

Gershom Bartlett, Winged Face, 1766, Granite, Enfield – American Antiquarian Society, Farber Gravestone Collection

As his work increased in popularity, Bartlett found himself carving stones for a variety of customers from the surrounding population. In fact, his business cut across social boundaries to include the urban and rural, the rich and poor. But as Bolton’s population grew (thanks in part to its ample supplies of mineral rock), nearby land became increasingly expensive. This hindered Bartlett’s land speculation efforts. Consequently, in 1772, he purchased inexpensive land on the Vermont frontier and moved his family there shortly after. Bartlett’s gravestone production in Connecticut ceased in 1773 but, as Richard Gagne shows in his study of the master carver’s work, Gershom continued his craft. Well over 300 of his stones have been identified in graveyards north of Connecticut.

By the time he left Connecticut, Gershom Bartlett had become the most prolific gravestone carver in the colony’s history. He carved most of his stones in the popular 18th-century style with a central arch and rounded shoulders, but he also carved rectangular and pyramid-shaped stones. His portfolio of over 1,000 stones found in more than 70 cemeteries in almost 50 towns, provides historians with vital records about travel, demographics, technology, and commerce in the early colonies. In addition, the rich, detailed epitaphs Bartlett carved in these pieces are telling records of life, death, and familial relationships in 18th-century New England.