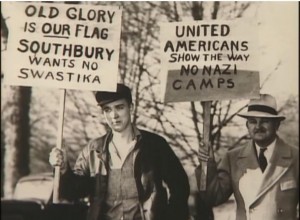

In the late 1930s, in an attempt to avoid a second world war, countries around the globe worked to curb increasingly hostile Nazi aggression through policies of appeasement. The United States did its part by not only avoiding military intervention in Europe but also by allowing the German-American Bund (the American wing of the Nazi party) to set up camps across the country. When the Nazis moved into Southbury, however, local citizens reacted forcefully, eventually pushing the anti-Semitic settlers out of the state.

German-American Bund Plans Youth Camp in Kettletown

Southbury was a peaceful farming community of about 1,200 people when, on October 1, 1937, Stamford resident Wolfgang Jung purchased 178 acres of land in the community’s Kettletown district. Nobody thought much of the purchase until about 6 weeks later when residents noticed a large group of people working feverishly to clear the land for construction. As it turned out, Nazi loyalists in the US had designs on turning the area into a camp for Nazi youths.

The camp was to be named Camp General von Steuben and work in tandem with similar Bund Youth Movement camps in Yaphank, Long Island, and Andover, New Jersey, to provide gathering places for Nazis in the Bronx, Westchester, and all of Connecticut. According to the Hartford Courant, plans called for construction of a youth hostel, “five or six acre swimming pool,” and facilities capable of supporting 1,100 people. Designers also planned to alter a nearby abandoned road for use by the New Haven Railroad.

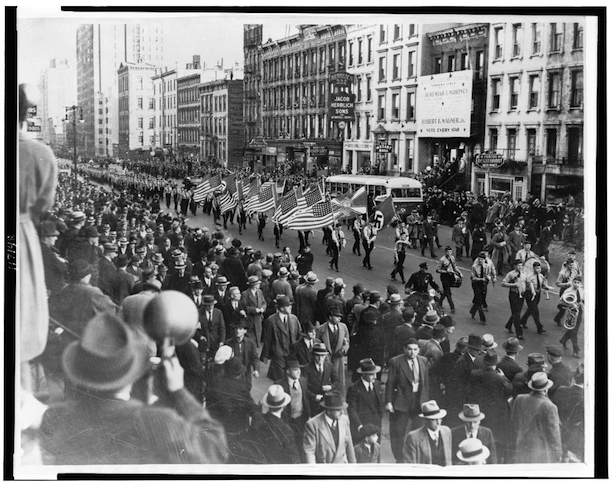

Image from the film Home Front: During World War II – Co-produced by Connecticut Public Television and Connecticut Humanities as part of the Connecticut Experience series on CPTV.

A Town Rallies

Once a local newspaper made the Nazis’ plans public, Southbury residents reacted swiftly. They called for a town meeting to discuss changing Southbury’s zoning laws. Mass mailings went out to local neighborhoods warning them of the danger in their community, and pastors at Southbury churches began preaching anti-Nazi rhetoric.

Before the eagerly anticipated town meeting, local residents and law enforcement agents moved to slow progress at the camp site. On Sunday, December 5, 1937, Gustav Kron and Richark Koehler (two Bundists from New York) began clearing brush at the site when a wave of policemen stormed the camp and arrested the two men for violating Connecticut blue laws by working on the Sabbath. (The two men were eventually released on a $75 bond).

On December 14th, after town officials moved their meeting to the South Britain Congregational Church because of the massive local turnout, the legislature approved new zoning laws that designated the land in Kettletown as appropriate for farming and residential use only—making the operation of any camp in Kettletown subject to a $250 fine. Though some questioned the constitutionality of the measure, it passed by a vote of 142-91.

With their message clearly conveyed, the town dropped its charges against Korn and Koehler at their December 27th trial. Soon after, the Bund announced that their Kettletown camp was not “central enough” in location to serve their needs. They promptly sold the property and threatened to build a new camp elsewhere in the state, but never did.