By Kelly Marino

Wethersfield’s Sophia Woodhouse Welles made a name for herself as an inventor and a businesswoman in antebellum America when few women worked outside the home or earned a wage. Welles’s methods for producing bonnets not only provided high-quality fashionable products in the United States, but they also influenced the industry at the international level.

A Teenage Entrepreneur

Sophia was born in Wethersfield, Connecticut, to John and Sarah Buck Woodhouse in 1799. The large family was involved in agriculture, and Sophia had multiple siblings.

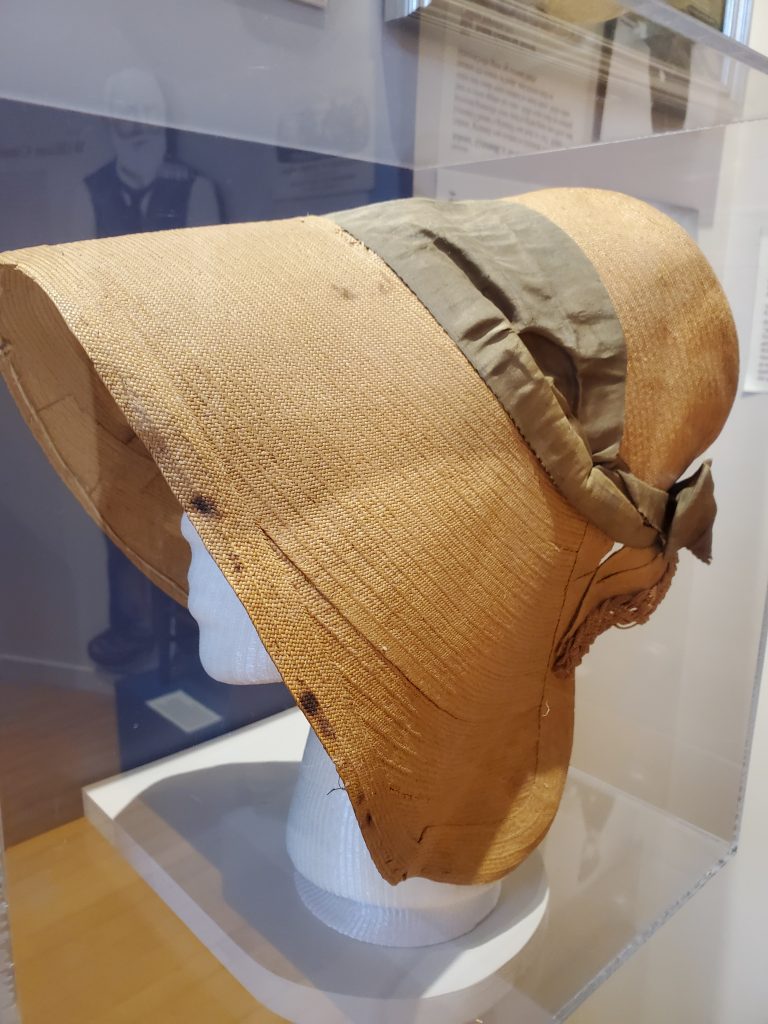

At only 19 years old, Welles earned international acclaim by developing new methods for treating, drying, and braiding spear grass to construct bonnets in the popular Leghorn style. She recognized that spear grass taken from near the Wethersfield part of the Connecticut River made sturdy material for her product and allowed her to show off her braiding skills.

In addition to winning several state and international awards for her bonnets, the London Society of the Arts recognized her talent with a medal and monetary prize. Hoping to learn more about her technique, they asked her to submit samples of spear grass and seeds to study bonnet making in Europe. Reviewers commented on the “fineness of the material” and “beauty of its colour.” They believed that they could cultivate the grass in places such as Great Britain and Ireland and argued her bonnets were even better quality than their Italian counterparts.

Award-winning Bonnets Fill a Void

National consumers welcomed Welles’s innovations as strict embargo acts prevented Americans from freely purchasing desirable items from other countries. At the time, Leghorn bonnets—produced in Italy—proved especially popular with the public, but importation restrictions made them difficult to acquire. The stylish bonnets included a removable and replaceable ribbon that women could change depending on preference, dress, or season, making them versatile. They could also decorate the bonnets with flowers, feathers, or other materials.

Welles’s successful business blossomed as word got out about her bonnets, contributing to the growth of New England’s hat and bonnet industry in the 19th century. Customers included well-known figures such as First Ladies Dolley Madison and Louisa Adams.

Welles eventually hired other Wethersfield women and trained them to help her in the production process. She had a shop at home and gave women piecework to return to her when completed, creating an industry run and powered by women in the small town. Welles inspired others in places such as Danbury, Milford, Norwalk, South Norwalk, and Stamford where the hat industry grew. By 1900, Connecticut ranked first in the nation in production, known for making around a third of all hats manufactured in the United States.

Welles Closes Up Shop

Sophia married Gurdon Welles in 1820 and they lived in the Titus Buck house on Main Street near Wethersfield Cove where her husband supported her endeavors. Welles and her husband received a patent for her work in 1821. After her marriage, however, Welles began focusing more on family affairs than bonnet production. (Records suggest the couple had ten children, which created larger domestic responsibilities.) She ultimately stopped producing bonnets commercially in 1835 when a fire prompted her to close her shop. Today, samples of her bonnets can be viewed at the Wethersfield Historical Society and Keeney Memorial Cultural Center.

Kelly Marino is an Assistant Lecturer of History at Sacred Heart University.