By Donna K. Baron

In 1807, the Goshen Congregational Church in Lebanon bought a barrel organ for its new meeting house. (Goshen was the third or south ecclesiastical society within Lebanon.) Goshen-born Erastus Wattles built the instrument, which he called a “Pan-Harmonicum.” This purchase, the first of its kind for the town, marked a transition in attitudes toward the type of music appropriate for Puritan worship.

Changing Attitudes toward Music

Until the late-1700s, New England’s Puritan congregations, such as the Goshen Congregational Church, rejected anything that hinted of Roman Catholic worship practices—choirs, musical instruments, or singing anything except the Psalms. Psalms were rewritten in standardized meters so that the same texts could be sung to different tunes. A male precentor would lead the members by choosing the tune and singing two lines at a time, which the congregation would repeat. This form of singing was called “lining out” or, later, Old Way singing. The sound was loud, slow, and very plain. There was no harmonizing and the rhythms were very simple.

Later in the 18th century, American clergy started pushing for musical reforms similar to those taking place in England. Soon, despite the many conservative church members who believed fervently in Old Way singing, congregations adopted hymn singing with multiple parts. This became known as “regular singing.” These changes paved the way for the development not only of sacred song but secular music as well.

As New England churches adopted congregational hymn-singing, many also added instruments to help keep singers on tempo and pitch. Smaller, portable instruments, such as drums and church basses (a bowed string instrument, often slightly larger than a modern cello), proved popular with country churches, in part, because they were relatively affordable. Organs, however, represented a larger investment and typically required a community to hire or have on hand a musician capable of playing the instrument.

Wattles’ Pan-Harmonicum

Erastus Wattles, born in Goshen in 1778, earned his living as a maker and dealer of musical instruments. Of the instruments he crafted, one of his clarinets, featuring an ivory mouthpiece and keys, survives in the collection of the Church History Museum of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah. Wattles also composed music. Two of his compositions, “Owen’s March” and “Governor Strong’s March,” were included in the 1816 Instrumental Preceptor, a book of musical instruction compiled by William Whiteley who was probably an apprentice to Wattles.

For churches, larger barrel organs, such as Wattles’ Pan-Harmonicum, represented an alternative to the traditional pipe organ. These mechanical musical instruments housed bellows and one or more ranks of pipes in a wooden case. The organ operated by means of a hand crank or by a weight or spring-driven clock work. The motion turned a wooden cylinder, or barrel, encoded to produce a specific piece of music by means of staples and pins precisely arranged along its surface. As the barrel rotated, it moved levers which, in turn, caused air from the bellows to move through the pipes to create sound.

This rudimentary form of automation removed the need for the church to employ an organist. Some barrel organs, however, could also be played by means of a keyboard. Such combination-organs gave churches the flexibility to choose between an automated or human organist, as circumstances allowed. Lebanon resident Orramel Fitch described another Pan-Harmonicum made by Wattles as “an incredible music machine, 14-1/2 high, 10-1/2 feet wide, and 4-1/2 feet deep, with an organ in the lower part, and in the upper, every conceivable musical instrument in multiples, all run by ‘machinery which is impelled by weights.”

Music Stirs Lebanon Congregation

At the dedication of the Goshen Congregational Church organ, Reverend William Lyman of East Haddam preached the sermon. Lyman noted the mixed blessing of adding such an instrument to services. Certainly, instrumental music could be used for ill, “enlivening the giddy throng.” Further, he emphasized, “The design of musick is to produce agreeable and lively sensations within. Some kind of musick is agreeable to most people. On certain persons it has a surprising operation…and can carry them almost into regions of ecstasy.” Still, this very same capacity could also “captivate, warm and enliven the soul of piety.”

Lyman’s description of the service’s conclusion suggests that, from his perspective at least, even those who remained doubtful about the church’s new organ were moved by its music. “According to previous agreement,” Lyman wrote, “the singers rose, the organ sounded and the whole house was filled with melody. The audience was surprised into a pleasing extasy [sic] and the elevating power was felt to an unusual degree.”

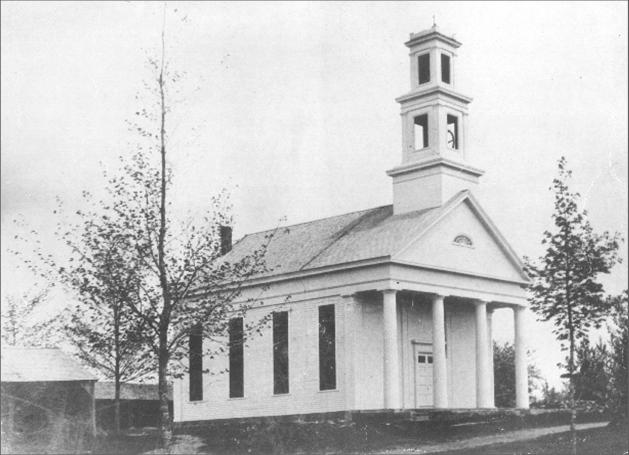

The meeting house for which Wattles built the Pan-Harmonium burned to the ground in 1898. It is not known if it was still in the building at the time and, unfortunately, no further records on this, Wattles’ first Pan-Harmonicum, are known to survive.

Donna K. Baron is director of the Lebanon Historical Society and co-curated its exhibition “Long, Long, Ago”: Lebanon’s History through its Music 1800-1940 with consulting curator Sarah Griswold.