By Gregg Mangan

P. T. (Phineas Taylor) Barnum of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was one of the greatest entertainment entrepreneurs in history. His traveling shows, museums, and world-famous circus helped him amass a multi-million-dollar fortune on his way to becoming personal friends with such iconic figures as Abraham Lincoln, Queen Victoria of England, and Mark Twain. His inventive marketing campaigns solidified his standing as the father of modern advertising and showmanship.

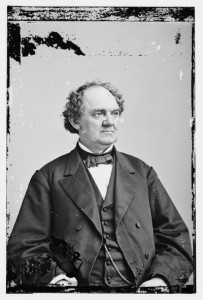

P. T. Barnum – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Working in an age when blue laws throughout the United States restricted socially acceptable forms of entertainment, Barnum provided amusement and wonder to the masses. He sought out attractions from around the globe that he used to exploit the public’s curiosity and desire for the thrilling and the risque. Historian Irving Wallace noted that, as a showman, Barnum gave “New York, and then America, and finally the world, the gift of enjoyment.”

The Early Life of a Practical Joker

P. T. Barnum was born on July 5, 1810, in Bethel, Connecticut, a small town about four miles southeast of Danbury. His father, Philo Barnum, was a farmer, tailor, tavern keeper, and grocer, who had 10 children by 2 wives. Phineas was Philo’s sixth child and the first by his second wife, Irene. Throughout Phineas’s childhood, Bethel was a stronghold of conservative values dominated by the Congregational church. To combat the drudgery and routine of everyday life, men like Phineas’s maternal grandfather (also named Phineas) resorted to one of the few socially permissible forms of entertainment, the practical joke.

Barnum recalled that his grandfather “would go farther, wait longer, work harder, and contrive deeper, to carry out a practical joke, than for anything else under heaven,” as biographer A. H. Saxon noted. It was his grandfather’s boisterous personality and love for harmless and amusing deception that Phineas employed during his meteoric rise in the entertainment industry.

The “Prince of Humbugs”

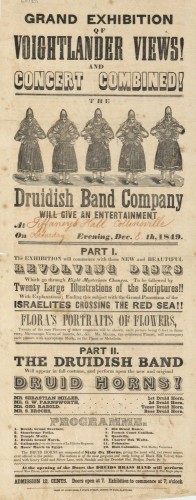

Druidish Band Company advertisement, 1849 from one of Barnum’s early musical acts – Connecticut Historical Society

Phineas was described as a strong student who excelled in mathematics and despised physical labor. He worked for his father on their farm and later in a family-owned general store. After his father’s death in 1825, Barnum liquidated the family assets and went to work at a general store in Grassy Plains just outside Bethel, where he met and married Charity Hallet, his wife of the next 44 years.

His career as the self-proclaimed “Prince of Humbugs” was launched at the age of 25 when a customer named Coley Bartram entered the grocery store Barnum had started with John Moody. Bartram knew Phineas had a weakness for speculative investments, and he was looking to sell a “curiosity.” Joice Heth, an African American woman alleged to be 161 years old and former nurse to founding father George Washington, drew crowds of curious onlookers willing to pay for the chance to hear her speak and even sing. Barnum jumped at the opportunity to market her performances.

Never one to risk understatement, Barnum marketed Joice Heth as “the greatest curiosity in the world,” according to Raymund Fitzsimons in his book Barnum in London. He flooded the New York area with posters and advertisements. When interest in Heth began to wane in New York, Barnum took her through New England, attempting to increase sales by claiming Heth was using the proceeds from the tour to buy her great-grandchildren out of slavery. When interest in Heth began to fade a second time, Barnum sent an anonymous letter to the Boston press claiming that Heth, who was a small elderly woman, was not a person at all but instead an automaton—a word then for a mechanical figure—made of whalebone, springs, and rubber. Barnum later claimed that the public’s need for amusement justified his hoaxes. While there is no record of Barnum ever saying, “There is a sucker born every minute,” biographer Wallace wrote that the showman did say “the American people liked to be humbugged.” If “humbugging” and exaggeration pleased his audiences, Barnum saw no harm in it. Since Barnum’s time, however, humbugs that involved making public spectacles of individuals based on their race or physical characteristics have received deserved scrutiny by a number of scholars.

Museum his “Ladder” to Fortune

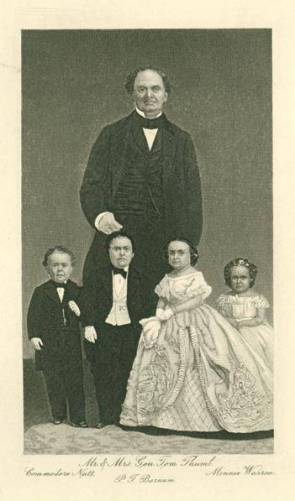

Mr. & Mrs. Tom Thumb, Commodore Nutt, Minnie Watson, and P.T. Barnum – Connecticut Historical Society

In 1841 Barnum learned that Scudder’s American Museum, a collection of $50,000 worth of “relics and rare curiosities” located in New York City on lower Broadway, was for sale. His purchase and grand reopening of the attraction as “Barnum’s American Museum” was what he called “the ladder” by which he rose to his fortune.

Barnum was relentless both in tracking down oddities and in promoting his museum. He set powerful floodlights and giant flowing banners atop his building. He advertised free roof-top concerts and then supplied the worst musicians he could find in hopes of driving crowds away from the noise and into the relative peace of the museum. Once inside, patrons were treated to a spectacle of “giants,” Native Americans, dog shows, a working replica of Niagara Falls, and even the famous Feejee Mermaid (later revealed to be a monkey torso and fish tail meticulously joined together). In the three years leading up to Barnum’s purchase, Scudder’s American Museum had grossed $34,000. In the first three years of its operation under Barnum, the newly renamed museum grossed more than $100,000.

In 1842, during a stopover in Bridgeport, Connecticut, the showman discovered Charles Stratton, a boy who would elevate Barnum’s fame to international levels. Stratton was four years old at the time of their meeting, was only 25 inches tall and weighed 15 pounds. Playing on America’s fascination with exotic European attractions, Barnum marketed Stratton as “General Tom Thumb, a dwarf of eleven years of age, just arrived from England.” Barnum and Stratton packed houses in America and embarked on a European tour where they met Queen Victoria of England, King Louis-Philippe of France, and other monarchs.

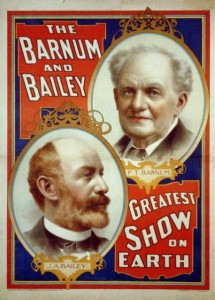

An 1897 poster advertising The Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth – Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Retirement and a Disastrous Book

After managing a 150-concert tour for “Swedish Nightingale” Jenny Lind—a tour that brought him to new peaks of fame in the early 1850s—Barnum settled into the first of several uneasy retirements. He spent time with his wife and three daughters in his Bridgeport mansion, which he had named “Iranistan.” There, in his elaborate Moorish-style mansion, he wrote a controversial autobiography that detailed the degree to which he had duped audiences while amassing his fortune. The backlash from its release in 1855 was severe, and readers felt betrayed and swindled by Barnum’s deceitful practices. The New York Times accused Barnum of obtaining success through “the systematic, adroit, and persevering plan of obtaining money under false pretenses from the public at large,” as quoted in the foreward to a 2000 edition of Barnum’s autobiography. Barnum spent years rewriting and attempting to control the damage from his book’s revelations.

A Career in Politics

After a series of poor financial decisions, including an investment in the bankrupt Jerome Clock Company of New Haven, Barnum was broke and forced to go back out on the road. In 1858 he gave a series of lectures around London entitled, ironically, “The Art of Money-Getting, or Success in Life,” that were very popular. His lectures and dedication to his New York museum helped revitalize his popularity, which eventually encouraged Barnum to run for public office.

“It always seemed to me,” Barnum once wrote (and is quoted in Wallace’s biography), “that a man who ‘takes no interest in politics’ is unfit to live in a land where the government rests in the hands of people.” Taking this philosophy to heart, Barnum won election to the Connecticut Legislature from the town of Fairfield in 1865. He fought for the citizenship of black men and women as proposed in the Fourteenth Amendment and worked to limit the power of the New York and New Haven Railroad lobby. Barnum’s successes got him reelected a year later. His most satisfying political work came during a one-year stint as mayor of Bridgeport in 1875. While in office, he crusaded to lower utility rates, improve water supplies, and close the city’s houses of prostitution.

The years that encompassed his political career also included a second failed attempt at retirement, the death of his wife Charity, a marriage to Nancy Fish a year later, and the launch of what became his most famous entertainment venture, the circus.

Barnum & Bailey Circus

In April of 1874 P. T. Barnum’s Great Roman Hippodrome had opened on an entire square in New York City between Fourth and Madison avenues. Barnum traveled around the world purchasing animals and attractions for the new Hippodrome. Despite the confidence that he owned the “Greatest Show on Earth,” Barnum saw a rival circus, known as International Allied Shows, as a threat to his success. He entered into merger negotiations with Allied’s James A. Bailey, laying the foundation for what ultimately became the Barnum & Bailey Circus.

Iranistan, residence of Mr. Barnum, ca. 1851, Bridgeport – Connecticut Historical Society and Connecticut History Illustrated

“Mr. Barnum, America”

In his later years, Barnum enjoyed reading and became a collector of oil paintings, never losing his passion for a good practical joke. He also never seemed to tire of his iconic status, reveling in the fact that a letter reached him all the way from Bombay (now Mumbai), India, that was addressed simply to “Mr. Barnum, America.”

Barnum died in his sleep on April 7, 1891, at his home in Bridgeport—a waterfront mansion named Marina; Iranistan had been destroyed by fire in 1857. After his death, Charles Godfrey Leland, a former Barnum employee quoted in the Wallace biography remembered him as “very kind-hearted and benevolent and gifted with a sense of fun which was even stronger than his desire for dollars.” On measuring his professional career, Barnum was credited by the Times of London as pioneering the profession of “showman on a grandiose scale,” and The Washington Post declared him “the most widely known American that ever lived.”

Gregg Mangan is an author and historian who holds a PhD in public history from Arizona State University.