In a wooded area of Barkhamsted near Ragged Mountain lie the remains of a once thriving multicultural community. Now known as the Lighthouse Archaeological Site, this village, founded in the middle of the 1700s, consisted of people of African, Native, and Anglo-European heritages living harmoniously on the fringes of mainstream society. Once abandoned, the site left behind an archaeological legacy detailing the challenges of daily life in colonial Connecticut.

Around 1740, tradition holds that Mary Barber (also known as Molly), a white woman from Wethersfield, Connecticut, made the decision to marry a Narragansett Indian from Block Island named James Chaugham. To escape her disapproving father, Mary and James took to the woods of northwestern Connecticut; they eventually settled along the Farmington River in what became the town of Barkhamsted. While some details of the story (such as Mary’s Wethersfield origins) have not been conclusively proven, church and town records—along with archaeological evidence—document the growth of a small community where the Chaughams made their new home.

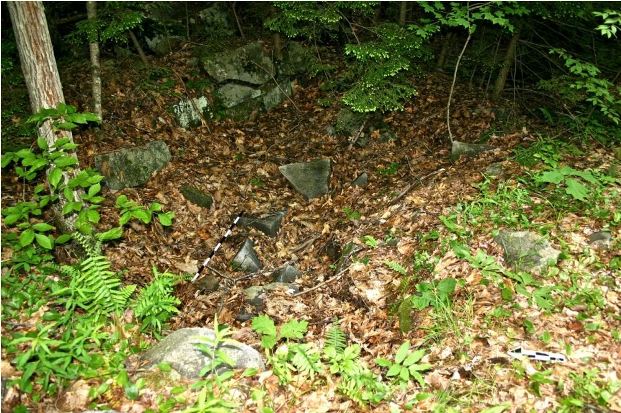

Lighthouse Archaeological Site: Quarry, Barkhamsted – Connecticut Freedom Trail

Initially isolated, the Chaugham’s settlement slowly grew thanks to their eight children and a demographic shift that brought increasing numbers of people into northwest Connecticut in the latter part of the 18th century. Six of the Chaugham children married, some to the new arrivals who, like Isaac Jacklin a freeman of African descent from Hartford, hailed from diverse backgrounds.

Eventually, entrepreneurs improved a trail at the base of Ragged Mountain to accommodate stagecoach traffic. This trail became a part of the Farmington River Turnpike system and helped facilitate travel to the iron forges prospering in upper Litchfield County. One version of the Chaugham’s story credits stagecoach drivers with giving the Lighthouse settlement its name. As the story goes, drivers moving along the turnpike at night used to point out the light coming from the Chaugham’s residence in the distance and refer to it as if it were a landlocked version of a lighthouse at sea.

Former Village Now Lighthouse Archaeological Site

James Chaugham died in 1790, but Molly, who historians speculate lived to be well over 100, survived him for approximately another 30 years. Despite the deaths of the Chaughams, the Lighthouse community continued to survive, albeit largely in poverty, until the middle of the 19th century. By then, economic and social factors facilitated the slow abandonment of the property as families moved away in search of work, land, and other opportunities.

What the Lighthouse people left behind, however, was over a century of archaeological evidence, including tools, ceramics, clay pipes, iron nails, and food remains. Recognizing its archaeological and historical significance, the Connecticut Historic Preservation Council designated the area a State Archaeological Preserve in 2008, placing it under the care of the State Department of Environmental Protection. Also listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the few small cellar holes and gravestones that remain act as a reminder of what it meant to live life on the “outside” of the dominant forms of Anglo-European colonial society during Connecticut’s formative years.